Blue Genes

CONTENTS

For Susan,

without whom I would not be living

Round and round she goes...

Where she stops nobody knows.

CARNIVAL PITCHMANS DITTY

Why are you so obsessed with death?

J. ANTHONY TO HIS BROTHER, CHRISTOPHER, SUMMER OF 1996

Im not. Im obsessed with living.

CHRISTOPHERS REPLY

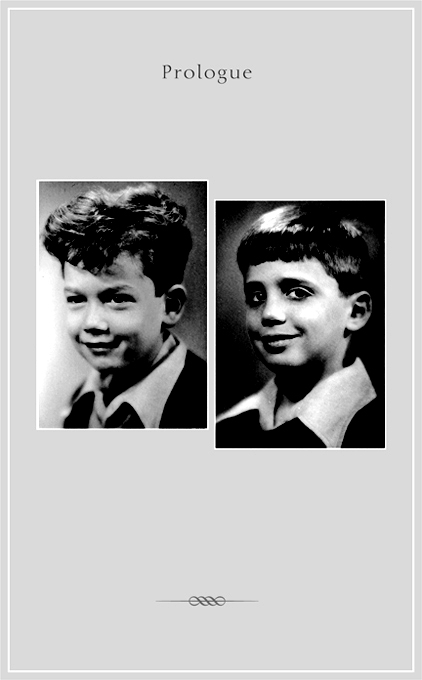

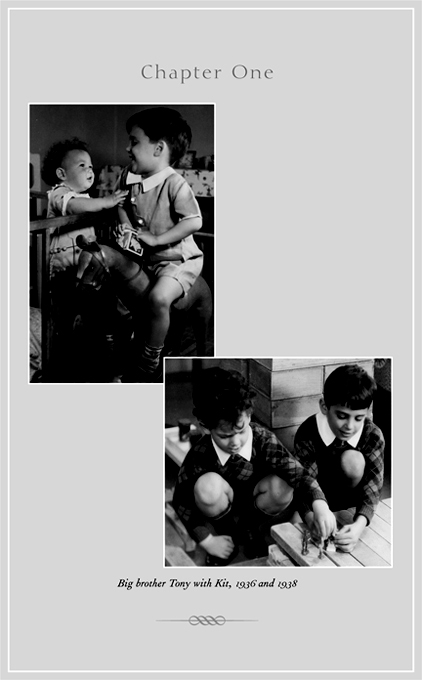

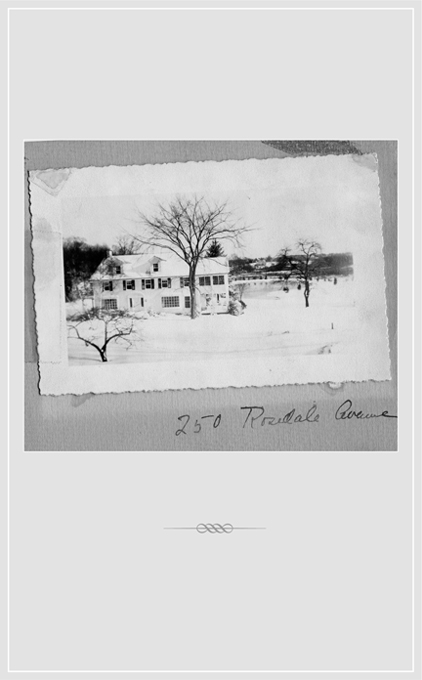

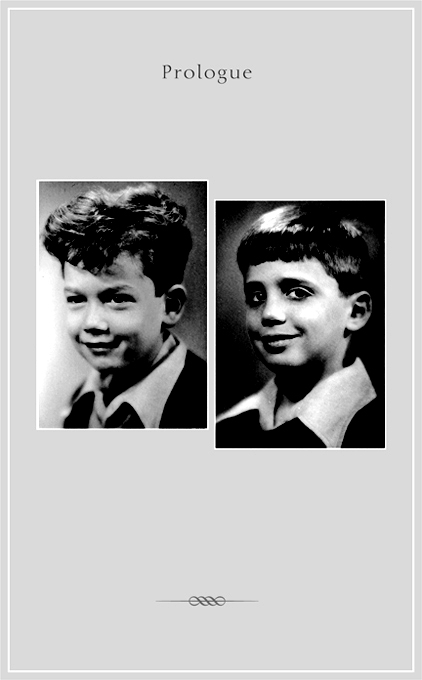

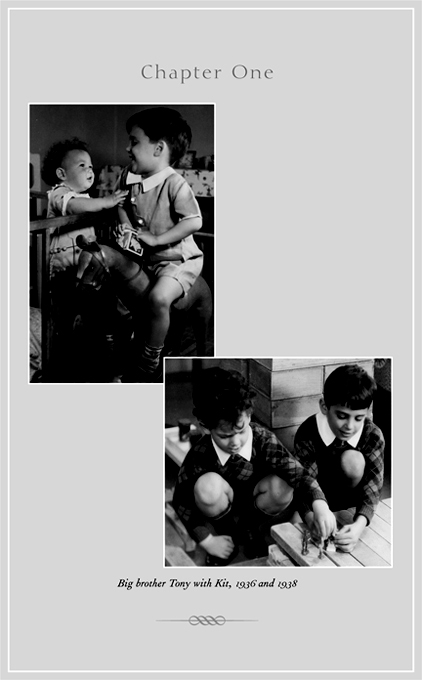

ON A LUSH MAY AFTERNOON IN 1940, my seven-year-old brother, Tony, and two of his pals from the second grade at the one-room schoolhouse down the road were playing one-o-cat baseball in our front yard. Yard is not quite accurate. The elegant, ten-room Revolutionary-era house in which my parents, my brother, and I lived for a few years in the late 1930s and early 40s was on seven acres of land. A small lake had been dug in the back of the house; rosebushes lined the south end of the property; and a small wooded area led, by a winding path, to a private school some miles awaya school to which my family hoped we would eventually go.

In short, we were upper-middle-class. Four white people, served by a colored staff of two, in prewar Westchester County, New York: privileged, select, unaware of the national, international, and personal doom that would soon descend upon us.

The stretch of greensward in front of our house was big enough for three young boys to debate the rules and practices of a game they had only recently learned, to ignore and place on the sidelines Tonys five-year-old brothermyselfand still leave room for batting, running, and catching.

The game was full of the sounds of boyhood play.

Youre out. Im not. You didnt touch me. I dont have to. That was out by a mile.

I could clearly see that the game would be more enjoyable if they invited me to play. More pleasurable for them (another out-fielder) and more fun for me. But in Tonys view, I was too young to pitch, field, or bat. I was an outsider, not an outfielder. I was his awkward brother.

To me, none of that mattered. What I cared about was being left out. And, having asked politely several times to be includedand having been rudely deniedI decided to grab the means of production, the baseball bat, and see what transpired.

What happened not only says a lot about how Tony would approach the world in the next fifty-five yearsas he sought and secured for himself jobs on major American newspapers, won two Pulitzer prizes, and wrote five important booksbut also would establish the nature of our fractious relationship, a hands-off, hands-on kind of brotherhood that, in the end, was worlds away from the type of bond we wished to have. Fate got in the way.

While Tony and his friends debated a point of baseball arcana, I hid the bat behind my back, its knobby end showing clearly above my head.

Tony asked me to give it back.

No, more accurately, he demanded I give it back. By now, not sure of my position, as the three seven-year-olds began to advance on me, I grabbed that knobby end and began to spin the bat around my head.

If you dont stop, Ill hit you, I declared, not exactly sure how Id achieve that goal, but sure that giving in now would decide my fate for the rest of the afternoon.

The others stopped, but Tony continued toward me.

Give me the bat, Kit.

Not unless I can play.

Youre too young.

Im not. If you come any closer, Ill let go.

Tony was not frightened by my threat. In the years that followed, he would never be frightened by anyones threats. He saw a frontal attack as the best course of action.

He advanced. I swung. How I aimed, I dont know, but the bat went straight to his temple and knocked him to the ground.

The other boys flew to their homes.

I ran into the house, sure that I had killed my brother.

Blue Genes

SOME PEOPLE ARE DISTURBED MOST by events that are unexpected.

For me, it has always been the half-awaited ones that carry the blow: the semiconscious fears that lurk behind closed eyes, the half-dropped pair of shoes, the what-ifs.

JUNE 5, 1997, 11:00 P.M.

Susan and I return home from a party. In an unusual show of activity, our answering machine has had eleven hang-ups and one messagefrom Linda, my sister-in-law.

Christopher, she says, can you call me, please.

Usually, no one calls me Christopher except strangers, but maybe Linda is echoing my brother, who sometimes calls me by my full name as a joke.

I make a mental note to call her tomorrow; its too late tonight. I figure that shes probably planning a publication party for Tony, who has just finished his latest book, nine years in the writing.

The book before this oneCommon Groundresulted in his second Pulitzer Prize and dozens of other awards. One reporter called my brother the best journalist of our generation. Another said he was the patron saint of contemporary reporters. He has won numerous accolades for his reporting for the New York Times, has received honorary degrees for his deep analysis of crucial episodes in recent American history, and has been wined and dined by literati and academics alike. He is, in short, one of those remarkable men whose work received enormous respect and attention.

But Tony is not sure that the new book, a huge volume called Big Trouble, is up to his previous works. Its due out in a month or so, and well all have to wait.

While Im at the closet, taking off my shoes, the phone rings again. Susan is near and she answers.

Hello. A pause. How? Her voice is electric, alarmed. I recognize a disaster in the making.

I come around the corner of the closet, a shoe in one hand, the other still on my foot.

She looks at me, the phone to her ear, shaking her head, a look of terror on her face.

What is it? I ask, already feeling the pain begin.

Tony killed himself, she says.

I scream and throw the undropped shoe at the far wall.

MOST BROTHERS HAVE SIBLING-RIVALRY PROBLEMS, interrupted by close bonding, but Tony and I always seemed to have great difficulty in finding common ground. The history of our family is partly responsible, a history full of self-destructive events.

In the wake of a family suicide, there is sorrow, guilt, despairand anger. My reaction to my brothers death was no different; in fact, because of the difficult relationship we had had, it may have been worse.

Next page