T HE solution of the mystery surrounding Amelia Earharts disappearance is an amazing story that has never been told.

The recent discovery of long-lost documents has finally enabled the authors to relate the events that led to solving the mystery. The story of Earharts final flight is told in what we hope is an easy-to-read narrative style, yet the book is packed with important historic documentation.

As radio operators transmissions were translated into plain language, any change or even shading of the original meaning was avoided. When a scene-setting or other verbal bridge was constructed to aid the flow of factual material, we took care not to inject poetic license into any matter of consequence. To ensure integrity, notes at the end of the text will guide the interested reader to the original source for complete verification.

Americas foremost woman flier disappeared more than sixty years ago. Some of the language, as well as aviation and radio terms used in the 1930s, may be unfamiliar now. The terms that need explanation are defined as they appear in the book.

First, we will follow the progress of Earharts flight from her perspective, revealing only the information that was available to her. Later, we will examine the flight from the viewpoint of those waiting for her at Howland Island. The comparison plainly reveals the tragic sequence of events that doomed her flight from the beginning.

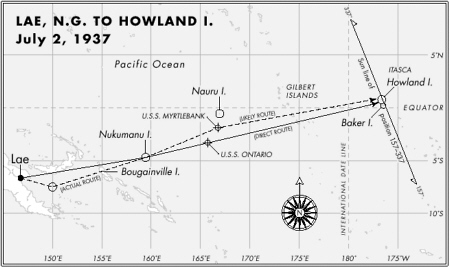

The story begins as Amelia Earhart is leaving Lae, New Guinea, for Howland Island.

1 : TRAGEDY NEAR HOWLAND ISLAND

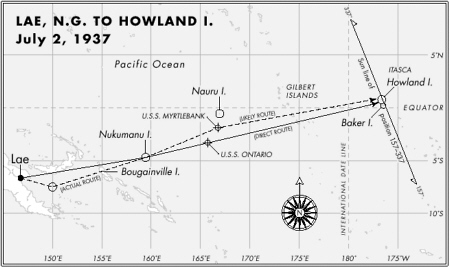

F RIDAY morning, July 2, 1937, Lae, New Guinea. It was not yet ten oclock, but the tropical sun already beat down unmercifully on the twin-engine Lockheed Electra. Inside the closed cockpit, Amelia Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, could feel the heat build as they taxied away from the Guinea Airways hangar.

The heavily loaded plane lumbered slowly across the grassy airfield toward the far northwest corner. Soon they would take off southeastward toward the shoreline, to take advantage of a light breeze blowing off the water. When they reached the jungle growth at the end of the field, Earhart swung the plane around to line up with the runway for departure. Only 3,000 feet long, the grass runway ended abruptly where a bluff dropped off to meet the shark-infested waters of the Huon Gulf.

Earhart was preparing to take off with the heaviest load of fuel she had ever carried. She and Noonan had flown 20,000 miles in the previous six weeks. Now only 7,000 miles of Pacific Ocean separated them from their starting point in California. The Electra, nearly 50 percent overloaded, was weighted to capacity with 1,100 gallons of fuel for the 18-hour flight to the next stop, Howland Island. Less than a mile wide, two miles long, and twenty feet high, their destination was just a speck of land that lay nearly isolated in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. It was truly a pioneering flight over a route never flown before, and they would be the first to land at the tiny islands new airfield. Two more firsts for the famous thirty-nine-year-old aviator, who upon reaching California would become the first woman pilot to have flown around the world.

Fred Noonan, at age forty-four, was famous in his own right. As chief navigator for Pan American Airways he had navigated the Pan American Clippers on all their survey flights across the Pacific. Now, both he and his pilot knew that the grossly overloaded takeoff would put their lives at great risk.

Fred watched closely as Amelia ran up each engine and checked it for proper operation. She gave the instruments a final scan, and they were ready to go. The moment of truth had arrived.

Amelia advanced the engine throttles full forward and released the brakes. The roaring, straining airplane slowly accelerated as it began its ponderous takeoff roll. Her feet were busy on the rudder pedals, moving them left, right, back, and forward to keep the plane going straight down the runway. They passed the smoke bomb that marked the halfway point to the shoreline. The tail wheel was already off the ground; they were going over 60 mph. There was no stopping the heavy plane now; it was fly or die, and the bluff at the end of the runway was coming up fast. Amelia applied back pressure on the control wheel to lift off the ground. The force required was lighter than she expected, and the plane over-rotated slightly as the wheels left the runway. She relaxed some of the pressure, allowing the nose-high attitude to decrease slightly.

They were off the ground, but their airspeed was too slow for optimum climb. When they were beyond the edge of the bluff, Amelia let the plane sink slowly until it was only five or six feet above the water. She signaled Fred to retract the landing gear, and the electric motor began cranking the wheels up into the nacelles to reduce drag. The seven seconds required to retract the landing gear seemed more like seven minutes as the engines struggled at full power to increase the airspeed.

After several seconds, Amelia could tell that she needed less back pressure on the control wheel to hold the craft level. This signaled that the battle between the engines and the drag of the airplane was slowly being won by the engines. The airspeed was increasing; they were going to make it. When the indicated airspeed increased to optimum climb speed, Amelia let the plane rise from its dangerous position just over the water. After they were safely a couple hundred feet in the air, she gently turned the plane to a compass heading of 073 degrees, direct for Howland Island. She reduced the engines to climb power and quickly scanned the engine gauges to check that everything was normal. They breathed easier as the plane slowly rose to the recommended initial cruising altitude of 4,000 feet.

Fred wrote down their takeoff time from Lae as 0000 Greenwich civil time (GCT), July 2, 1937. Having calculated that the flight to Howland Island would take 18 hours, they had to time their arrival to occur at daylight the following morning. Fred would need the stars to be visible for celestial navigation until just before they reached the island.

Amelia had arranged for a message to be sent from Lae to notify the Coast Guard cutter Itasca at Howland Island of her departure. The 250-foot Lake class cutter was waiting just off the island to provide communications, radio direction-finding, weather observations, and ground servicing for her flight. The captain of the