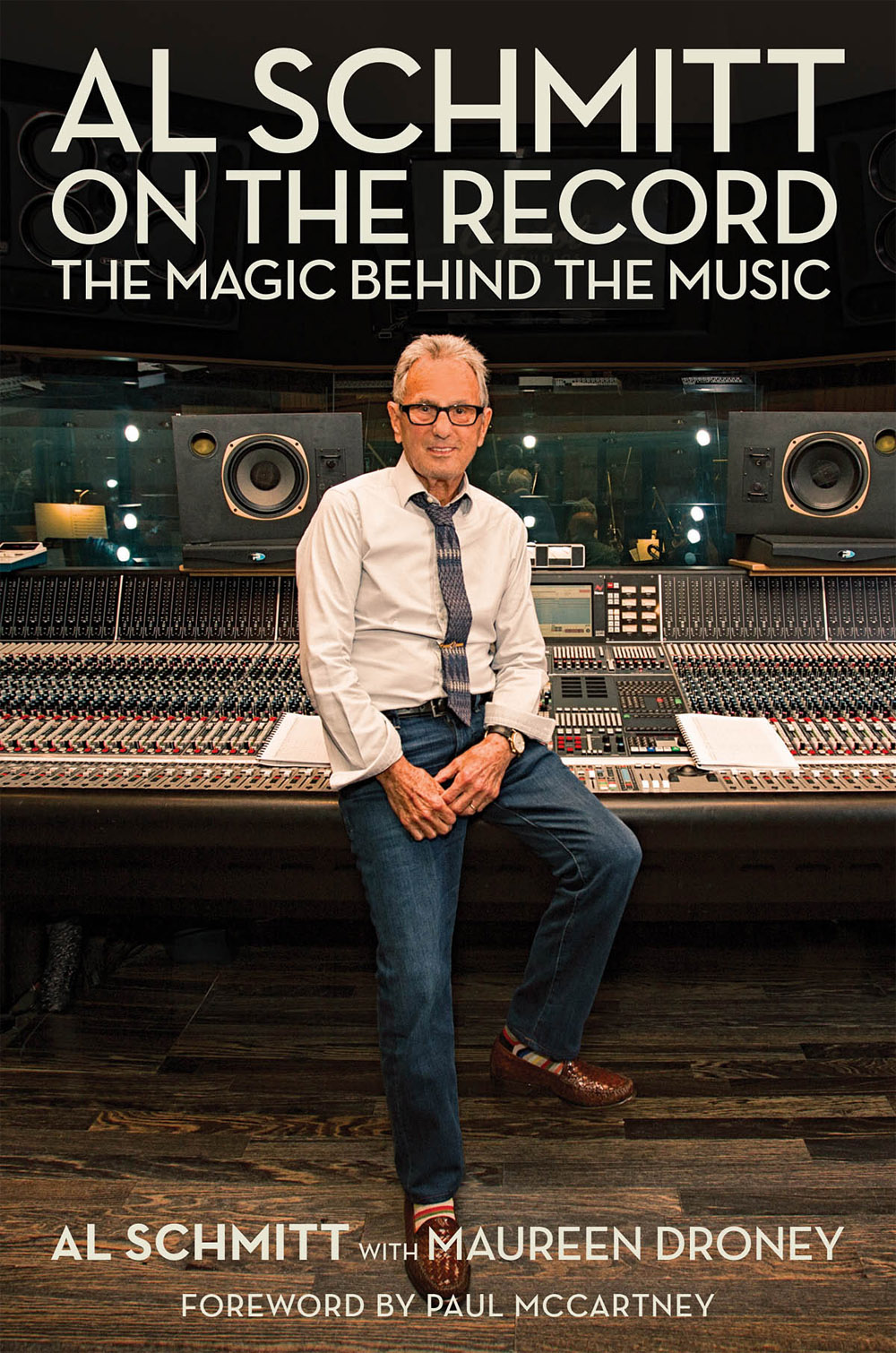

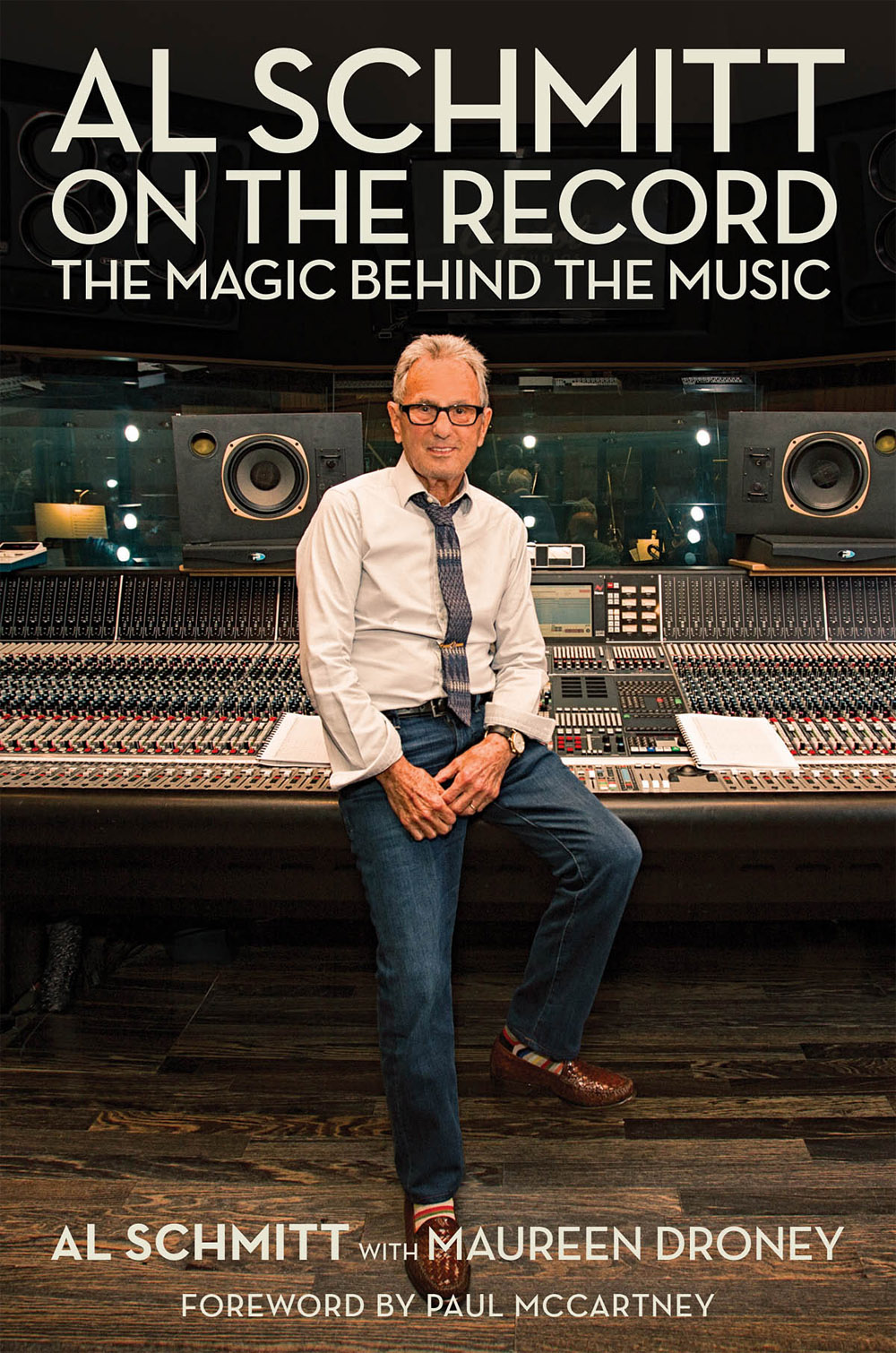

AL SCHMITT

ON THE RECORD

Copyright 2018 by Al Schmitt

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, without written permission, except by a newspaper or magazine reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review.

Published in 2018 by Hal Leonard Books

An Imprint of Hal Leonard LLC

7777 West Bluemound Road

Milwaukee, WI 53213

Trade Book Division Editorial Offices

33 Plymouth St., Montclair, NJ 07042

Printed in the United States of America

Book design by M Kellner

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Schmitt, Al, author. | Droney, Maureen.

Title: Al Schmitt on the record : the magic behind the music / Al Schmitt with Maureen Droney.

Description: Montclair, NJ : Hal Leonard Books, 2018. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018033584 | ISBN 9781495061059

Subjects: LCSH: Schmitt, Al. | Sound recording executives and producers--United States-- Biography.

Classification: LCC ML429.S337 A3 2018 | DDC 781.49092 [B] --dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018033584

www.halleonardbooks.com

To my wife, Lisa, and to my children,

Al, Karen, Stephen, Chris, and Nick

FOREWORD

by Sir Paul McCartney

WHEN I WORKED with Al and Tommy LiPuma on my Kisses on the Bottom album we would do a take, and when we had one that we thought was good enough, wed go into the control room to check it. This was always a revelation for me because Al had transformed the take into a great-sounding record. This is a skill that very few recording engineers have.

The various techniques that Al uses are a mystery to me and its such a joy to be working with someone who understands this magical process. Al would tell us stories of his experiences with everyone from Jefferson Airplane to Frank Sinatra and many other great artists. This encouraged me to share stories of my own, so the sessions were often more like social events than work.

More than all of this, Al is a great human being who cares deeply about what he does and the people he works with. He is admired by many recording artists and fellow engineers for these qualities.

I always wished I knew more about Al and so am very much looking forward to reading this book. Thank you, Al, for the wonderful times we have shared.

Love,

Paul

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

SPECIAL THANKS TO

Tom Dowd, Bob Doherty, Paula Salvatore, Niko Bolas, Phil Ramone, Tommy LiPuma, Steve Genewick, Bill Smith, and my friends and partners in METAlliance: Ed Cherney, Elliot Scheiner, George Massenburg, Chuck Ainlay, and Frank Filipetti.

AL SCHMITT

ON THE RECORD

BUT IM NOT QUALIFIED, MR. ELLINGTON!

___________

I WAS NINETEEN and just out of the navy when I started working at Apex Recording Studio on West Fifty-Seventh Street in Manhattan. Located on the second floor of the Steinway Building, it was a big room that sounded great. On the first floor of the building was the Steinway & Sons showroom.

In those days, jazz was the hottest thing happening in New York, and Apex had a reputation as the best place to record it. It was a top-notch studio, and getting a job there turned out to be a very lucky break for meespecially because, as it happened, Tom Dowd was working there as an engineer. Tommy was only a few years older than I was, and it was pretty early in his career. But hed already done a lot of recording and was starting to make a name for himself.

It was my Uncle Harry who had recommended me for the job. Harry was a well-known recording engineer, and starting from when I was a little kid, Id spent time helping out at his studio and learning the recording ropes. He knew that I was just out of the service and back home in New York, trying to figure out what to do next. He was also good friends with the owner of Apex, and when he heard about a job opening there, he put in a good word for me. I went for an interview and was hired as an apprentice. At the beginning, my job was mostly to help out on the sessions Tommy Dowd was doing, following him around and learning how things should be done.

After about three months, the studio manager thought Id learned enough to take on some of the work that we called little demo dates. They were pretty simple. People would come in with a song theyd written, to play piano and sing the song. Or a guy might come in to have himself recorded singing a song that he liked as a gift for his girlfriend. It was all mono, of course. We recorded on ten- or twelve-inch lacquer discs, depending on the length of the song, and we cut at 78 rpm. Wed set the level, run the lathe, and cut a disc. Then wed put it in a sleeve, collect the fifteen-dollar payment, and the customers would leave with something that they could play at home. The disc was pretty fragile, so they couldnt play it forever. But if they were careful, theyd get quite a few spins out of it.

After Id gotten a few of these dates under my belt, my boss thought I was doing well enough to come into the studio by myself on a Saturday, while the rest of the staff was off for the weekend, and record the demo sessions that were booked for that day. It was my first Saturday at the studio, and my first time there alone. But we had a schedule book that listed who was coming in, and there was a receptionist downstairs in the Steinway showroom who would let me know when a client was coming up.

It seemed simple enough, so I wasnt worried. According to the book, I had three people coming in, one at ten a.m., one at noon, and one at two p.m. I got there early and was set to go when the first person came in at ten. He played guitar and sang Happy Birthday to his daughter, I recorded him, and that was it. The noon session was a guy who played piano and had written a song. I put a mic on him and a mic on the piano, got the balance while he ran it through, and then cut his disc.

When that was done, I waited for my two oclock, which was, according to the book, someone named Mercer. I liked to meet the clients when they arrived, and so would stand by the elevator where I could greet them as they got off. Then Id take them into the studio. So, when the receptionist buzzed a few minutes before two to say that my client was on the way up, I was ready and waiting at the elevator for Mr. Mercer.

But when the big brass elevator doors opened up in front of me, five guys came walking out carrying instrument cases. One of them asked me where the studio was.

I said, The studio is right here, sir. But were booked, we have a session.

The one whod spoken laughed and said, Youre waiting for Mercer, right?

Yeah, thats right, I answered.

That would be Mercer Ellington, he replied. Were here to record with the Mercer Ellington band. Duke will be here, too.

I must have turned white with shock, because, instantly, fear overtook me. I honestly felt like my heart was going to stop beating. I was a bebopper; I loved jazz and big bands. I understood what was supposed to happen and who these guys were, but I had absolutely no idea what to do about it. Some of the musicians coming out of the elevator carrying their instruments were my heroes. They were the virtuosos, the players from Duke Ellingtons band, like Billy Strayhorn on piano and the great Johnny Hodges on saxophone. For this session, they were going to be working with Mercer Ellington, Dukes son.

What I learned later was that Duke and Mercer, along with the famous and very influential jazz critic Leonard Feather, were partners in a label they called Mercer Records. As it turned out, all three of them were going to be there that day for the session.

Next page