Praise for Everything Is Cinema

Meticulously detailed A story of transformation, a painstaking account of a lifelong artistic journey.

The New York Times Book Review

Godard changed the movies as much as the American masters he grew up on: Welles, Hawks, Hitchcock, and the rest. He is as original as Picassobut unlike Picasso, he has been denied the biography he has always deserved. This is it. Just at the moment when the New Wave turns fifty, Richard Brody has given us Everything Is Cinema , a remarkable book, which describes with sharp intelligence a great and elusive artists times, intellect, passions, and work.

Wes Anderson

Geniuses all have their flaws, and Brody goes to great lengths to contextualize these without excusing them, the better to unmask and explain this famously inscrutable artist and his work. All in all, Brody has given us the most satisfyingand epicmovie biography of the year so far.

DGA Quarterly

Everything Is Cinema is better than a biography, it is a novel. And a great novel, in which one discovers the story of a man who almost picked the wrong art form, a struggling writer who became an immense filmmaker.

B ERNARD -H ENRI L VY

Enthralling, exhaustive, and, above all, unwilling to swallow the mass opiate that says Godards post-1960s work is somehow less than what came before.

The Village Voice

Full of lucid analysis and human context, Richard Brodys book performs a heroic act in rescuing Godard and his growing shelf of works from the prison of myth and theory, from the cult of youth and the cult of the 60s, restoring him to his place as an engaged, hard-working artist.

J ONATHAN L ETHEM

The books principal virtue, underlying its trenchantly judged account, is Brodys determination to grapple with Godards public image while insisting on its inextricability from his personal crises. This multifaceted portrait provides something far more valuable and complex than a myth-busting corrective.

Film Comment

Richard Brodys biography of Godardarguably the most important, enigmatic, and exciting filmmaker of the second half of the 20th centuryeffortlessly weaves intellectual history, a personal saga, and an authoritative reading of the films themselves into a seamless web. It virtually crackles with intelligence, and is a must-read for anyone interested in cinema.

P ETER B ISKIND

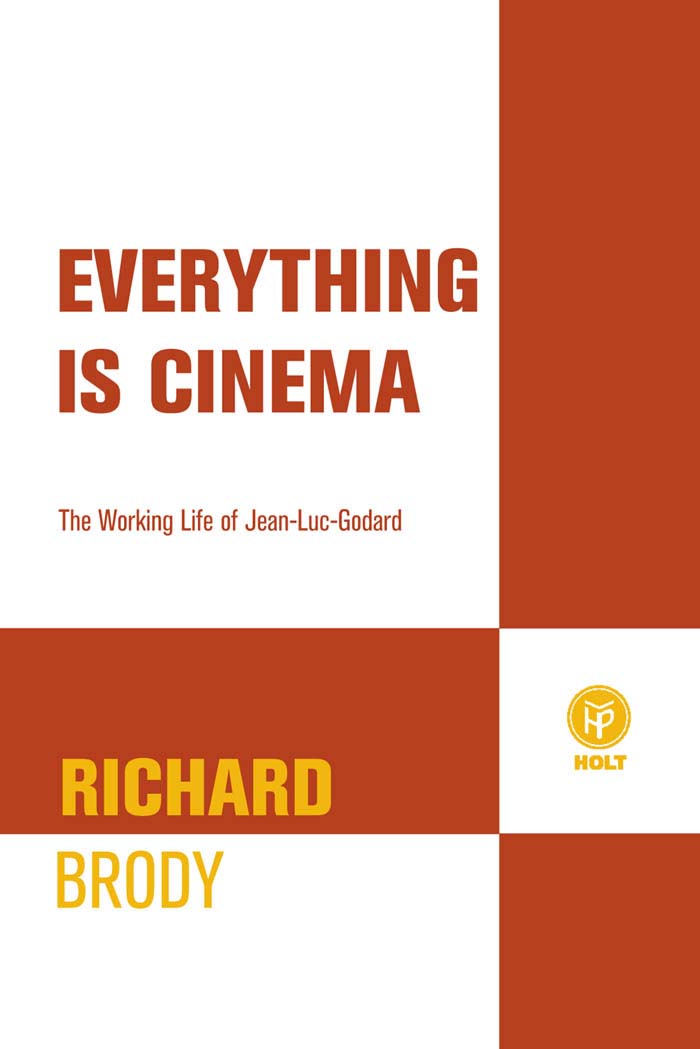

EVERYTHING

IS CINEMA

EVERYTHING

IS CINEMA

THE WORKING LIFE OF

JEAN-LUC GODARD

RICHARD BRODY

A HOLT PAPERBACK

METROPOLITAN BOOKS / HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY New York

Holt Paperbacks

Henry Holt and Company, LLC

Publishers since 1866

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, New York 10010

www.henryholt.com

A Holt Paperback and  are registered

are registered

trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

Copyright 2008 by Richard Brody

All rights reserved.

Distributed in Canada by H. B. Fenn and Company Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brody, Richard, 1958

Everything is cinema: the working life of Jean-Luc Godard/Richard Brody.1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8050-8015-5

ISBN-10: 0-8050-8015-5

1. Godard, Jean Luc, 1930Criticism and interpretation. I. Title.

PN1998.3.G63B76 2006

791.430233092dc22

[B]

2006047347

Henry Holt books are available for special promotions and

premiums. For details contact: Director, Special Markets.

Originally published in hardcover in 2008 by Metropolitan Books

First Holt Paperbacks Edition 2009

Designed by Meryl Sussman Levavi

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Maja, for my very being

CONTENTS

ONE . |

TWO . |

THREE . |

FOUR . |

FIVE . |

SIX . |

SEVEN . |

EIGHT . |

NINE . |

TEN . |

ELEVEN . |

TWELVE . |

THIRTEEN . |

FOURTEEN . |

FIFTEEN . |

SIXTEEN . |

SEVENTEEN . |

EIGHTEEN . |

NINETEEN . |

TWENTY . |

TWENTY-ONE . |

TWENTY-TWO . |

TWENTY-THREE . |

TWENTY-FOUR . |

TWENTY-FIVE . |

TWENTY-SIX . |

TWENTY-SEVEN . |

TWENTY-EIGHT . |

TWENTY-NINE . |

THIRTY . |

PREFACE

I N THE SPRING OF 2000 , J EAN -L UC G ODARD RECEIVED ME in his office in Rolle, a town on Lake Geneva in Switzerland, where he has been living and working for the past thirty years. Rolle is set on a sharply rising slope between the lake and the highlands. It is a sedate town. The main street has one traffic light. Mont Blanc hovers weightlessly in the distance.

When I arrived, Godard was seated at a broad, uncluttered trestle desk in a spacious office on the main floor of one of Rolles few modern buildings. He has one wall of compact discs, another of books and pictures, and from his chair, he faces out onto a roomful of video equipment that would do a small TV station proud: sturdy industrial metal racks holding tape decks, switchers, meters, monitors, a bulky sound console squat on the floor, dozens of cables and wires and plugs strung from one board to another, and a computer. A television monitor was on: Godard was keeping an eye on the mens semifinal matches at the French Open.

He welcomed me with the description of a cartoon he recalled from the pages of The New Yorker , the magazine for which I had come to interview him. The drawing shows a unicorn wearing a suit, seated at a desk, and talking on the phone. The caption reads, These rumors of my non-existence are making it very difficult for me to obtain financing. To Godard the cartoon seemed exemplary of his own situation. Happily, though, he continues to existand also to workat an extraordinarily high level of artistic achievement. Somehow, this fact is disturbingly unknown, except among a small coterie of film lovers. His work continues to be the subject of academic conferences and journal articles, and the intermittent DVD releases of his films are greeted by flurries of eager Internet postings among the tight circle of his devotees. But Godards name is no longer common currency in the film industry, or for that matter on the cultural radar. While enormous attention is given to filmmakers of more modest ability, Godard has become almost forgotten. But unlike Orson Welles, who struggled to make anything of value in his later years, or D. W. Griffith, whose career was stopped cold by changing fashions, Godard continues to develop. His obscurity is not hard to fathomhis work is demanding, but acceptance of its demands yields singular rewards, and, as the later chapters of this book will argue, his more recent films are indeed works of art fully equaland in some respects, superiorto the early pictures that made his reputation and established his celebrity.

Godard is undoubtedly best known for his first feature film, Breathless , which he made in 1959. A highly personal yet exuberant refraction of the American film noir, Breathless was gaudily emblazoned with its technical audacity as well as with Godards own artistic, literary, and cinematic enthusiasms. Even now, Breathless feels like a high-energy fusion of jazz and philosophy. After Breathless , most other new films seemed instantly old-fashioned. The triumph of Godards longtime friend Franois Truffaut at the 1959 Cannes festival with The 400 Blows , had announced to the world the cinematic sea change effected by a group of critics-turned-filmmakers already known in France by the journalistic label of la nouvelle vague , the New Wave. But The 400 Blows was only the setup. Breathless was the knockout blow. If The 400 Blows was the February revolution, Breathless was October.

are registered

are registered