First published by Verso 2009

This paperback edition published by Verso 2011

Emilie Bickerton 2009

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-84467-760-3

eISBN (US): 978-1-84467-831-0

eISBN (UK): 978-1-78168-963-9

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v3.1

Contents

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my colleagues at New Left Review, in particular Susan Watkins, Tony Wood and Perry Anderson for their comments on earlier versions of this book. Johanna Zhang for the picturestechnically, conceptuallyand our walks and talks where much of what follows became a little clearer. And thank you to all those who helped and advised me in different but invaluable ways: Christopher Bickerton, Sebastian Budgen, Tom Penn, Lorna Scott Fox, Michael Witt, Emma Wilson, Julien Plant, Laura Mulvey, Adam Shatz, Patrick Hayes. In Paris, many of those who lived the Cahiers story were kind enough to share their memories with me. Their time and gift for recounting such a remarkable tale allowed me to better understand the lived experience of writing for the journal. In particular, thank you: Raymond Bellour, Jean-Louis Comolli, Jean Douchet, Bernard Eisenschitz, Jean-Andr Fieschi, Andr S. Labarthe and Sylvie Pierre. For my family, as ever, my deepest gratitude: Hlne and David, Claire, Paul and Chris.

Charles Laughton, Night of the Hunter (1955)

Introduction

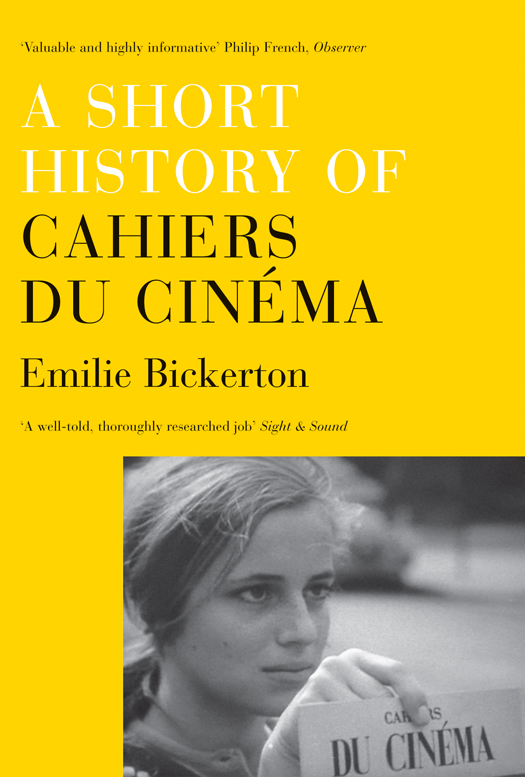

What follows is a familiar tale, and yet it has never been told. In its original conception the French film journal Cahiers du cinma had marked a break with the prevailing regimes of taste in the artistic culture of the post-war. In film this was defined by the silent tradition and French cinma de qualitglossy literary adaptations, costume dramas or musicalsboth unanimously celebrated for reasons motivated by patriotism or partisanship. Cahiers proposed a very different notion of cinema and turned consensus opinion on its head. Its writers believed that film was not only an entertainment industry but also an art at the beginning of its journey. Film had already produced a number of great masters, equal to Velzquez or Proust in their field. In the writing on film however, there was too much nostalgia for a bygone era. Old-guard critics were shut away in their decrepit palaces, cut off from the world like Billy Wilders fallen movie star in Sunset Boulevard. In the first issue Cahiers put it simply: this group of critics were lovers of a dead sun, they see ashes where a thousand phoenix are constantly reborn.

It was the last modernist project. As Jean-Luc Godard summed up in 1959:

We have won by getting the principle accepted that a film by Hitchcock is as important as a book by Aragon. The auteurs of films, thanks to us, have entered definitively into the history of art.

Bound in its original yellow covers, Cahiers was a real journal de combata magazine with a battle plan. It drew its polemical energy from the remarkable combination of individuals who made up its first editorial group. This eclectic team brought a mixture of Catholicism, classicism, humanism and metaphysics to the meeting with cinema. Born in a growing Cold War climate where public figures and debates were positioned vis--vis an emerging world order, Cahiers initially set itself apart. It focused on developing a deeper engagement with cinema built on aesthetic foundations. Such a rich body of work was in need of fuller understanding: at home there was Jean Renoir, and early pioneers Jean Vigo and Jean Epstein; the cinematographic landscape worldwide included Italian neo-realism through Roberto Rossellini and Luchino Visconti; in America the exiles Fritz Lang and Alfred Hitchcock worked alongside Samuel Fuller, Nicholas Ray and Billy Wilder; Yasujiro Ozu, Akira Kurosawa, Kenji Mizoguchi were active to the East. Such directors had to be defended in a coherent fashion, within the context of the history of art.

The process of viewing the films by these masters also provided Cahiers critics with an education in how to make films. The young Turks, as Claude Chabrol, Jean-Luc Godard, Franois Truffaut, Jacques Rivette and Eric Rohmer became known, were preparing their own practical intervention into the world of cinema, in which the journal was the first stage. Cahiers was their rancho notorious in one former editors phrase, evoking Fritz Langs hideaway for outlaws, a gathering place where the young menuntil Sylvie Pierres arrival in the sixties, no women worked at Cahierscould explore and find ways to articulate the genius they had seen in films. Here they could live and breathe the movies, argue and debate over the latest screening, find the right words to justify their passions and, crucially, meet some of the masters. Writing forced them to ask, and answer, how a director employed various techniques to his own unique ends, how he conveyed his narrative visually and developed a thematic continuity through his uvre. The years 19511959 were explosive ones for Cahiers, concluding triumphantly when Franois Truffaut collected the Palme dOr at Cannes. Having previously dismissed or denied the critical and now artistic radicalism coming from the magazines pages, critics internationally could only eat their words.

Up to this point, the story of the journal is broadly well known. These were the iconic yellow years, when some angry young men first cut their teeth before enacting the short-lived cinematic revolution of the New Wave. A few moments have become emblematic, and suffice to sum up this version of the magazines history. A young Jean-Pierre Lauds defiant stare at the camera in The 400 Blows; the jump cuts between Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg walking down the Champs-Elyses in Breathless; Miles Daviss jazz score narrating Louis Malles drama in an elevator, Lift to the Scaffold. These moments punctured the previous conception of what cinema could express and how. Suddenly the conventional studio settings, tight scenarios and rules of editing were replaced with low-budget techniques and audacious working methods. Small teams shot scenes on the streets and in friends apartments with mobile cameras and using direct sound; takes and tracking shots grew unusually long; experiments with editing led to the use of collage and jump cuts; the love affair with America brought in jazz and William Faulkner. The ethnographic cinma vrit practiced by Jean Rouch and Robert Flaherty met with noir plot lines full of guns, women and motor cars. But for all the eulogies that have subsequently been devoted to the New Wave, the movement was brief, over by 1965. Its influence was absolutely definitive, but the work itself was insubstantial. The ideas developed at