Table of Contents

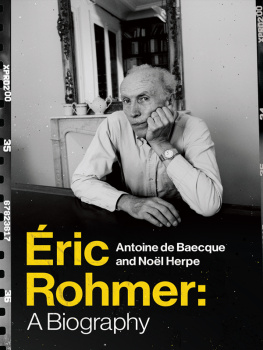

ric Rohmer

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright Editions Stock 2014

English translation 2016 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54157-2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Baecque, Antoine de author. | Herpe, Nol author. | Rendall, Steven, translator. | Neal, Lisa (Lisa Dow), translator.

Title: ric Rohmer : a biography / Antoine de Baecque and Nol Herpe ; translated from the French by Steven Rendall and Lisa Neal.

Other titles: ric Rohmer. English

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Includes filmography.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015041586 | ISBN 9780231175586 (cloth)

Subjects: LCSH: Rohmer, ric, 1920-2010. | Motion picture producers and directorsFranceBiography.

Classification: LCC PN1998.3.R64 B3413 2016 | DDC 791.4302/33092dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015041586

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Andrew Kopietz

Cover image: Robin Holland/Corbis Outline

Contents

W hat do we know about ric Rohmer?

Certain films are highly esteemed by film aficionados: My Night at Mauds, Claires Knee, The Marquise of O, Full Moon in Paris, A Tale of Summer, The Lady and the Duke A broader audience knows that Rohmer liked to film very young womenthe so-called Rohmriennessometimes presenting them as symbols of the period, simultaneously charming, revelatory, and annoying. He also introduced a few actors who went on to have successful careers: Fabrice Luchini, Pascal Greggory, and others. Abroad, Rohmer seemed to embody a very French way of filmmaking.

But is it known, for example, that taken all together his twenty-five full-length films attracted more than eight million spectators in France, and several million more around the world? ric Rohmer was not a pure product of Saint-Germain-des-Prs chic who made a limited number of films that were snobbish in a very Parisian way. In his work, sophisticated plots and delicacy of feeling went hand in hand with a classical ideal: their expression of emotions, their narratives, and their direction made his films capable of moving a broad audience while at the same time recording and expressing a certain atmosphere of the time in a critical or ironic mode.

Do people also know that another man, Maurice Schrer, was hidden behind the pseudonym ric Rohmer, which he adopted when he was more than thirty years old? That was the source of the nicknamele grand Momothat some of his oldest friends were to continue to use until the end of his life. He liked secrecy. More than that, it was probably the true passion of his life: knowing how to conceal himself, creating doubts, remaining far from the spotlight. A pronounced penchant for playing with masks led him to invent doubles for himself; he took on alternate identities that allowed him to sow confusion regarding his private life, to protect his anonymity, and even sometimes to remain clandestine.

At the age of twenty-five, just after the war, he published a novel with Gallimard under the pseudonym Gilbert Cordier. Shortly after the war, he wrote articles on film and directed his first short films under another pseudonym, ric Rohmer. A little later, in the mid-1960s, when ric Rohmer was looking for work, he sent out a couple of CVs: in one of them, he was born in Nancy on April 4, 1920, while in another he was the son of Louis Rohmer, professor, who after studying at the lyce of Nancy and at the faculty of letters in Lyon, had pursued a career as a professor of history and geography at a lyce.

Most of these statements are false. This predilection for manipulation allowed him to cover his tracks. Rohmer maintained ambiguity with undisguised pleasure, and for a long time it was hard to assemble reliable facts concerning his private life. In 1986, entrusting to Gilles Jacob and Claude de Givray a few letters he had written to Franois Truffaut, he admitted to Givray: In the event that you would like to publish passages in which reference is made, not to my articles on films but to me personally [] I would ask that you seek my approval. Because, you know, I guard my secrets jealously, even the old ones.

he assured a close friend. Maurice Schrer, a former professor of French, led an orderly life as a good son, good husband, and good father, a life into which ric Rohmer never penetrated, preferring a more Bohemian and less respectable one spent in the company of starlets and dandies, the dream life seen on movie screens. However, on closer inspection, ric Rohmers life was not that of a brilliant seducer, either. When he was asked the secret that allowed him to associate with all these ravishing creatures, he replied slyly: Absolute chastity. If he liked listening to actresses, it was first of all in order to propose stories or scenarios to them and to subtly fit them into the geometry of his productions.

ric Rohmers critical writing is sometimes overlooked; he was one of the great critics and theoreticians of his time and the editor in chief of the Cahiers du cinma. In 1955 he wrote a manifesto in five parts entitled Celluloid and Marble, in which he stressed the importance and the influence of cinema: Today one art possesses all the strength of this classicism and the splendid health that the other arts have lost forever. He thus legitimizes this major art and conceives the critics role as residing in a taste for beauty. Rohmer also enjoyed journalistic jousting and the polemics that surrounded films: he published a number of articles in Arts, the cultural weekly that was the Nouvelle Vagues iconoclastic, contrarian, and influential organ. In them we find a Rohmer who is fond of Westerns, defends Hollywood, and loves his actresses. A Rohmer who reacts to the films of his time, taking an opposing view, seeking to convince and to surprise a broad readership. He has to be restored to his place in critical thinking about the seventh art, and it must be emphasized that he is a genuine crivain de cinma.

If he liked to remain in the background, that is because he distrusted his own impulses and feared all kinds of excess. There is nothing more opposed to his character than the public display of an extremist or radical position. That did not prevent him from believing in values and affirming principles. Moreover, he enjoyed the discussion of ideas, the arts, and politics. He never hesitated to say that he was a conservative, seeing in the past a source of inspiration for the present and even for the future, and he long claimed to have a sensibility that was as royalist as it was Catholic. He was nevertheless not dogmatic: curiosity about the other, tolerance, and even a love for civilized contradiction and controversy define his cast of mind. This man of tradition and conversation was particularly sensitive to the arguments of militant ecologists and adopted them more and more overtly. He did not regard this as in any way incoherent on his part.

In June 2010, five months after his death, ric Rohmers family deposited his archives, as he had requested, at the IMEC (Institut mmoires de ldition contemporaine). Of his ninety years of life, there remain almost one hundred and forty document boxes containing more than twenty thousand items. It is thanks to this impressive corpus that we have been able to retrace not only each of Maurice Schrers parallel liveshis simultaneous careers as a teacher, critic, movie-lover, writer, and filmmakerbut also his main apprenticeships, readings, references, correspondence, and revealing centers of interest.