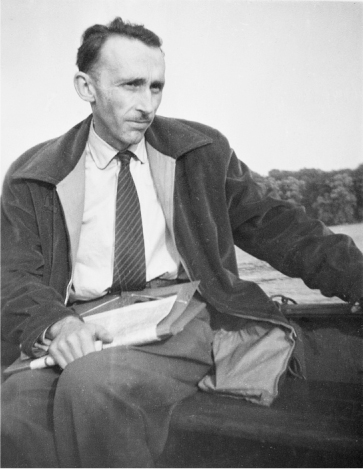

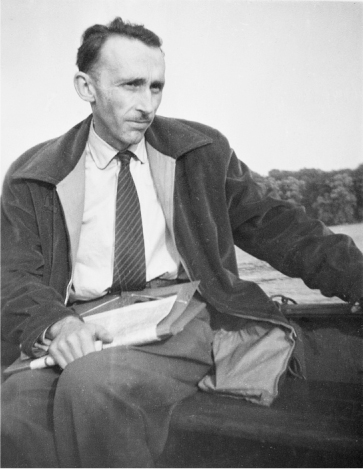

ANDR BAZIN

ANDR BAZIN

Revised Edition

Dudley Andrew

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research,

scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and certain other countries.

Copyright Oxford University Press 1978

Revised paperback edition copyright Dudley Andrew 2013

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

www.oup.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the

prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law,

by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization.

Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent

to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this

same condition on any acquirer.

A copy of this books Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress.

ISBN: 978-0-19-983695-6

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

For Stephanie Animator, critic companion still and always

figure de proue et passeur

CONTENTS

THE SECOND LIFE OF ANDR BAZIN

The Second Life of Andr Bazin refers first of all to the book you are holding, because this biography, originally written in 1978 and unexpectedly given a renewed appearance in 2013, takes account of additional photographs and facts, while it addresses a different readership in a different climate. Right at the outset let me acknowledge the enthusiasm and vision of Shannon McLachlan at Oxford University Press who, even during the arduous production of Opening Bazin, was so eager to follow through with this revised edition. I relied on Brendan ONeill, also of Oxford, not just for his ability to keep things on track but also for his swift and prudent advice, not to mention his enviable sangfroid. How gratifying to work with them on something so important to me. How important it was became clear when I saw the many precious photographs that Florent Bazin generously supplied, which brings me, and all of us, closer to his father.

For the most part my 1978 text stands here as it was written then. Why blanket the enthusiasm of youthful prose with mounds of primary and secondary sources that have since turned up? The endnotes frequently allude to obvious historical and bibliographical developments since then. So this edition lets me (and you, if you like) look not just at Bazin from a point well into the twenty-first century, but also at Bazin when he was discovered and debated in America during the flush of academic film study in the seventies. Bazin consumed me then, from the moment in 1968 when I was knocked over by his words till the publication of this biography exactly a decade afterward. Those were the very years during which the journal he founded, Cahiers du Cinma, taken over by Marxist, even Maoist, editors, thoroughly disowned him. Many of the reviews that greeted my account of his life demanded to know if Bazin was right about the cinema, or was he wrong? The question could be posed that baldly in those days, and the verdict could often go against him, because his belief in the congenital realism of photography stood in the way of the massive reformulation of film theory under semiotic, psychoanalytic, and ideological lines.

Certainly I was caught up in the fervor of film studies, generally supportive of the ideas and methodologies coming out of France; yet I promoted Bazin. This dual allegiance, befuddling at the time, no longer seems so difficult to maintain. For the rather crude question of the correctness of Bazins position has been displaced by the more historically sensitive question about his aptness. Our era would more likely ask how good an index he makes for France in the forties and fifties, or for cinema culture. How appropriate and, indeed, necessarynot how correctwere his ideas then, and how fertile are they for us now? What would he say were he in our midst?

Written just as Foucaults impact was beginning to register in the United States, this book belongs to what was then a troubled genre, the biography of an exceptional man, and my attitude toward it now is far more cautious than it was in 1978. Still, in rereading this text I find that, far from making Bazin an autonomous agent, I took him to be a point of exchange for cultural values and attitudes (philosophical, cinematic, theological, political). Like every human, Bazin can reveal in his life story the chevrons and the scars taken in daily battles with opposition and inertia. We relinquish a splendid resource if we insist on dissolving individuals into institutions, discourse, and social practices. Bazins private struggles (for example, to rectify aesthetics with cultural history, or to justify his affection for Hollywood and his disinterest in America, or to align his Catholic and his socialist impulses) trace deep fault lines within that public terrain. Even when his illness removed him physically from this terrain, he reproduced its seismic tensions in his reading and viewing, in the topics he chose to write about, and in the style that served his ideas. It is this visibility of tensions within the man that I would now stress in presenting Bazin or any human being.

And so I am doubly grateful that Jean-Charles Tacchella enlarged this biography with his appendix on the troubled years at LEcran Franais. It was there, if anywhere, that Bazin was entwined with the institutions he spoke to and through. The fact that Tacchella himself was bound up in these events, debates, and shifting configurations of power, ratifies the utility not just of biography but of autobiography, even after Foucault. As both critic and human being he possessed the extraordinary aptitude to be able to insinuate himself into the consciousness of foreign bodies, if I may use the term, and to imagine life from other centers of perception.

I would like to emulate Bazin in this, if only to better grasp the stakes of the debates over cinema that I was involved in during the seventies. Though dead, Bazin was a living part of those debates. And he seems even more alive today. The chance to bring him back into our midst encourages the following reflections on his identity and evolution, as well as on the aptness of my original text.

How little we know of Andr Bazin; how little we know of any fellow human, Bazin would have been the first to say. What do we know? Researching his life almost forty years ago, I interviewed his mother and his widow, Janine, in my miserable French. I spoke with the closest intellectual companion of his university days and with a former girlfriend from his surrealist period as he waited out the Occupation. I looked up those who knew him after the war at his workplace (

Next page