FOREWORD

By Senator John S. McCain, III

I was not quite nine years old when my grandfather died. My memories of him are few but vivid. He rolled his cigarettes with one hand. He knew the skill fascinated me and he would always make a show of performing it when he visited. When he used the last of his tobacco, he would make a present to me of the empty bag of Bull Durham, which I dutifully treasured.

During the war years, I became aware that my grandfather had become an important person, famous enough to grace the cover of magazines, making his company all the more appreciated. But his visits then were few and far between, which, my mother explained to me, was the normal course of things for the McCains in wartime. War, after all, had been my familys business for many generations, and its demands took precedence over the comforts of family life.

The memories I have of him from that time are of quick visits, often late in the evening, that he made as he traveled either back from or back to the Pacific Theater. My mother would rouse us from our beds and hurry us downstairs for a few stolen moments and a quick snapshot with our busy grandfather. He would greet us as effusively as ever, tease our grogginess away with his high spirits, joke and kid with us for a few minutes, tell us not to be any trouble to our mother, and then, as he gave us a few quick pats on the head, he would make for the door and the waiting car outside that would carry him back to a world at war. After I returned to bed, unable to sleep, I would imagine our next meeting when I might be able to coax a few war stories out of the old man.

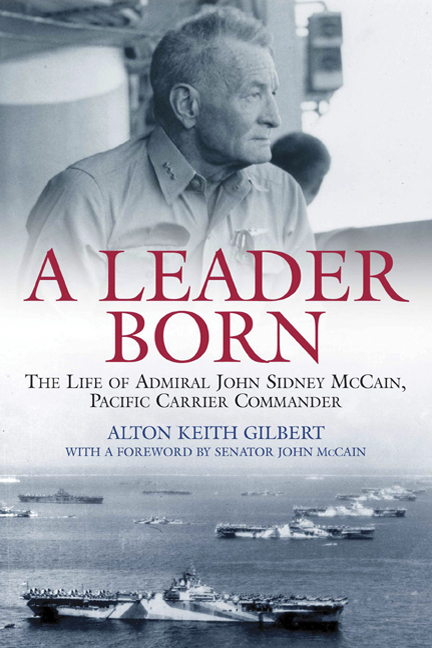

He was slightly built, short and rail-thin, with a surprisingly deep voice that ran up an octave when he was laughing, as he often was. He smoked constantly, cussed a blue streak, drank bourbon and branch water and gambled whenever he could. He wore a crushed cap, which the wife of one of his aviators had given him, and which he was quite superstitious about. He was as irregular in his appearance as it was possible to be in the United States Navy. When my grandmother tried to share with him an article about a new treatment for ulcers (which he suffered from), he slapped the magazine he was reading against his leg and shouted Not one dime of my money for doctors. Im spending it all on riotous living! He was unself-conscious, fun-loving, completely devoted to his service, and brave. He was, despite his long absences, the central figure of my familys life. My grandmother protected him. My mother adored him. He was my fathers ideal, and, after my father, he was mine as well.

His first duty was aboard a gunship, commanded by Ensign Chester Nimitz, cruising the Philippine Islands in the early years of the 20th century. He served aboard the flagship of Teddy Roosevelts Great White Fleet. He was fifty-two years old when he earned his naval aviators wings. He commanded all land-based aircraft in the South Pacific during the Solomon Islands campaign. He spent a couple of years in Washington as the Chief of Naval Aviation. And then, for the last year of the war, commanded Bull Halseys fast carrier task force, his last command and the one he most distinguished himself in.

When I think of him as a wartime commander, I conjure up an image of him, shared with me by someone who served with him, as if I had seen him there myself. Leaning on the railing of his flagship, Shangri-La , cigarette hanging from the corner of his mouth, watching unperturbed as a kamikaze prepared to dive toward him, and calmly counseling a comrade not to worry: Those five-inchers will get him.

He stood in the front row of officers aboard the U.S.S. Missouri as the Second World War ended. Later that day, he spent a few minutes alone with my father aboard a submarine tender in Tokyo Bay. Then he flew home to Coronado, where my grandmother had arranged a party to welcome him home. He fell ill and died that night. He was sixty-one years old, though he looked much older, worn down to an early death by the terrible strains of the war, and the riotous living he had so enjoyed. According to Admiral Halseys Chief of Staff, Admiral Bob Carney, he had suffered an earlier heart attack at sea and managed to keep it hidden. He knew his number was up, Carney observed, but he wouldnt lie down and die until he got home.

My father could not get home in time for the funeral and burial in Arlington National Cemetery. Just as well, he told my mother, because it would have killed me. I dont think my father ever knew a single day, through the many trials and accomplishments of his own life, when he didnt mourn the loss of his father. Their love for one an other was complete. While the demands of their shared profession often kept them apart, their deep respect for each other, and for their shared sense of honor, made the bond between them as strong as any I have ever observed. My father would become the first son of a four star admiral to reach the same rank. He credited the accomplishment to his fathers example.

My father spoke of him to me often, as an example of what kind of man I should aspire to be. But much of what I know of my grandfathers experiences as a senior commander in the war I learned from officers who led the Cold War Navy but came of age in World War II, who recorded their oral histories for a Naval Institute project. Many of them had served under or knew and admired my grandfather, and mentioned him respectfully. Histories of the naval war in the Pacific usually include a few lines or paragraphs about him. But no one has ever authored a full scale biography of this colorful, courageous and dedicated war fighter until now.