CONTENTS

For Doug, Andy, Sidney,

Meghan, Jack, Jimmy, and Bridget

PREFACE

PREFACE

A survivor of Auschwitz, Viktor Frankl wrote movingly of how man controls his own destiny when captive to a great evil. Everything can be taken from man but one thing: the last of human freedomsto choose ones own attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose ones own way.

I have spent much of my life choosing my own attitude, often carelessly, often for no better reason than to indulge a conceit. In those instances, my acts of self-determination were mistakes, some of which did no lasting harm, and serve now only to embarrass, and occasionally amuse, the old man who recalls them. Others I deeply regret.

At other times, I chose my own way with good cause and to good effect. I did not do so to apologize for my mistakes. My contrition is a separate matter. When I chose well I did so to keep a balance in my lifea balance between pride and regret, between liberty and honor.

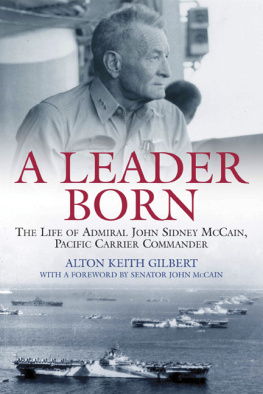

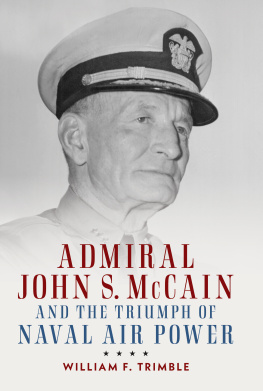

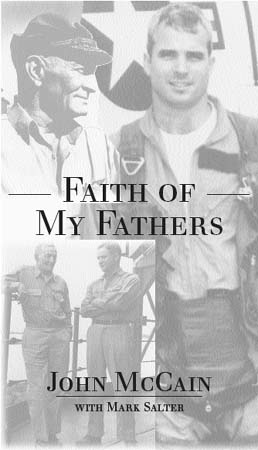

My grandfather was a naval aviator, my father a submariner. They were my first heroes, and earning their respect has been the most lasting ambition of my life. They have been dead many years now, yet I still aspire to live my life according to the terms of their approval. They were not men of spotless virtue, but they were honest, brave, and loyal all their lives.

For two centuries, the men of my family were raised to go to war as officers in Americas armed services. It is a family history that, as a boy, often intimidated me, and, for a time, I struggled halfheartedly against its expectations. But when my own time at war arrived, I realized how fortunate I was to have been raised in such a family.

From both my parents, I learned to persevere. But my mothers extraordinary resilience made her the stronger of the two. I acquired some of her resilience and her felicity, and that inheritance made an enormous difference in my life. Our family lived on the move, rooted not in a location, but in the culture of the Navy. I learned from my mother not just to take the constant disruptions in stride, but to welcome them as elements of an interesting life.

The United States Naval Academy, an institution I both resented and admired, tried to bend my resilience to a cause greater than self-interest. I resisted its exertions, fearing its effect on my individuality. But as a prisoner of war, I learned that a shared purpose did not claim my identity. On the contrary, it enlarged my sense of myself. I have the example of many brave men to thank for that discovery, all of them proud of their singularity, but faithful to the same cause.

First made a migrant by the demands of my fathers career, in time I became self-moving, a rover by choice. In such a life, some fine things are left behind, and missed. But bad times are left behind as well. You move on, remembering the good, while the bad grows obscure in the distance.

I left war behind me, and never let the worst of it encumber my progress.

This book recounts some of my experiences, and commemorates the people who most influenced my choices. What balance I have achieved is a gift from them.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I could not have written this book without the encouragement and assistance of many people to whom I am greatly indebted. My mother, a natural storyteller if ever there was one, reminded me of a great many family stories I had either forgotten or had never heard before. She was quite generous with her time despite her initial suspicion that I was just trying to show off. My brother, Joe McCain, keeper of family papers and legends, was an invaluable help in organizing and fact checking.

My fathers dear friend Rear Admiral Joe Vasey (ret.), who time and again interrupted his busy schedule to answer at length my many queries, gave me the best sense of my father as a submarine skipper and a senior commander. Moreover, he directed me to a wonderful website, hometown.aol.com/jmlavelle2, the work of Admiral Vasey and Jim Lavelle, which is a fountain of information about the experiences of the officers and crew of the USS Gunnel, one of the submarines my father commanded during World War II. I cannot praise or thank them enough for keeping the memory of their service alive and on-line.

Many thanks are due as well to Admiral Eugene Ferrell, my old skipper, who reminded me of how proud I was, so many years ago, to have learned from a master ship handler how to be a sailor. Veteran war correspondent Dick OMalley, a friend and keen observer of my grandfather during the war, told me many good tales about the old man in his last days at sea.

My old friend and comrade Orson Swindle reviewed the manuscript and kindly marked for excision anything that smacked of self-aggrandizement. Keeping me honest is a role he has often played in my life and will, I hope, continue to play for a good while longer. My Academy roommate Frank Gamboa resurrected a few stories from our misspent youth that I had managed to bury years ago. Lorne Craner, son of my dear friend Bob Craner, shared many of his fathers memories of our time in prison, and was a great help in sorting out times and places that I had gotten thoroughly confused.

Dr. Paul Stillwell, director of the Oral History Project at the Naval Institute, kindly allowed me to read the interviews of my father and many of my fathers and grandfathers contemporaries, a wonderful resource for anyone interested in learning about the men who made the modern U.S. Navy. I am grateful for the assistance of Chris Paul, who spent a part of his vacation sorting through volumes of my fathers papers. Thanks also to Joe Donoghue for successfully tracking down information and photographs that had eluded me.

Three others deserve special recognition and gratitude. Academy graduate, Vietnam veteran, and gifted reporter Bob Timberg, who often gives me the unsettling feeling that he knows more about me than I do, was a great source of encouragement and guidance. Just as important, Bob suggested that I meet with his agent, and now mine, Philippa (Flip) Brophy, who succeeded where others had failed by convincing me that Mark Salter and I could write a good story. She was a patient, steady influence throughout the drafting of the manuscript, as was my editor, Jonathan Karp. Although Jon is the only editor I have ever worked with, I cannot imagine how anyone could have done a better job. He and Flip kept us on track and calm, a tough assignment when working with a couple of amateur writers.

Finally, both Mark and I would like to thank our wives, Cindy McCain and Diane Salter, and our children for tolerating yet another demand on our time that kept us from our more important, and better loved responsibilities. Any merit in this book is due in large part to the help of the kind souls named above.

John McCain

Phoenix, Arizona

I

Faith of our fathers, living still,

In spite of dungeon, fire and sword;

O how our hearts beat high with joy

Whenever we hear that glorious word!

Faith of our fathers, holy faith!

We will be true to thee till death.

Frederick William Faber,

Faith of Our Fathers

Next page

PREFACE

PREFACE