Random House | New York

Contents

In memory of the valor of

John S. McCain Jr.

and Chester D. Salter Jr.

To have courage for whatever comes in life

everything lies in that.

MOTHER TERESA

Why Courage Matters

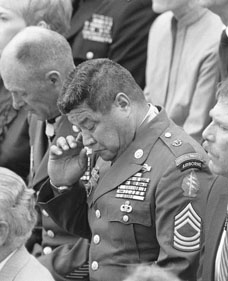

A KIND OF MADNESS is how a friend of mine, a Marine Corps veteran of the Vietnam War, described the courage displayed by men whose battlefield heroics had earned them the Medal of Honor. Its impossible to comprehend, really, even if you witness it.... Its one mad moment. You never think anyone you know is really capable of it. Not even the toughest, bravest, best men in the company. Theyre as surprised as anyone to see it. And if someone does do it, and lives, they probably never do it again. You might think the guy whos always running around in a fight, exposing himself to enemy fire, yelling a lot, might do it. But thats not what happens. They just get killed usually.

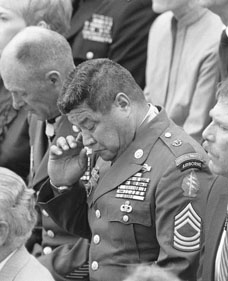

Master Sergeant Roy P. Benavidez during funeral ceremonies at Arlington National Cemetery, 1984.

AP/WIDE WORLD PHOTOS

Select at random a dozen Medal of Honor recipients and read the citations that accompany their decorations. Some will describe a single lonely act of heroism, one mans self-sacrifice that saved the lives of his comrades, who will remember the act for the rest of their lives with feelings of gratitude and lasting obligation mixed with something that feels much like shameshame that ones life, no matter how good and useful, no matter how honorable, might not deserve to have been ransomed at such a cost. All the citations will record acts of great heroism, of course. But some might seem plausible, if just barely so. The reader might even fantasize himself capable of such heroism, under extreme circumstances, without feeling too ashamed of the presumption. Maybe you are. At least one, however, will tell of such incredible daring, such epic courage, that no witness to it could imagine himself, or anyone he knows, capable of it. It might be the story of Roy Benavidez.

Special Forces master sergeant Roy Benavidez was the son of a Texas sharecropper. Orphaned at a young age, quiet and mistaken as slow, derided as a dumb Mexican by his classmates, he left school in the eighth grade to work in the cotton fields. He joined the army at nineteen. On his first tour in Vietnam, in 1964, he stepped on a land mine. Army doctors thought the wound would be permanently crippling. It wasnt. He recovered and became a Green Beret.

During his second combat tour, in the early morning of May 2, 1968, in Loc Ninh, Vietnam, Sergeant Benavidez monitored by radio a twelve-man reconnaissance patrol. Three Green Berets, friends of his, and nine Montagnard tribesmen had been dropped in the dense jungle west of Loc Ninh, just inside Cambodia. No man aboard the low-flying helicopters beating noisily toward the landing zone that morning could have been unaware of how dangerous the assignment was. Considered an enemy sanctuary, the area was known to be vigilantly patrolled by a sizable force of the North Vietnamese army intent on keeping it so. Once on the ground, the twelve men were almost immediately engaged by the enemy and soon surrounded by a force that grew to a battalion.

The mission had been a mistake, and three helicopters were ordered to evacuate the besieged patrol. Fierce small arms and antiaircraft fire, wounding several crew members, forced the helicopters to return to base. Listening on the radio, Benavidez heard one of his friends scream, Get us out of here! and, So much shooting it sounded like a popcorn machine. He jumped into one of the returning helicopters, volunteering for a second evacuation attempt. When he arrived at the scene, he found that none of the patrol had made it to the landing zone. Four were already dead, including the team leader, and the other eight were wounded and unable to move. Carrying a knife and a medic bag, Benavidez made the sign of the cross, leapt from the helicopter hovering ten feet off the ground, and ran seventy yards to his injured comrades. Before he reached them, he was shot in the leg, face, and head. He got up and kept moving.

When he reached their position, he armed himself with an enemy rifle, began to treat the wounded, reposition them, distribute ammunition, and call in air strikes. He threw smoke grenades to indicate their location and ordered the helicopter pilot to come in close to pick up the wounded. He dragged four of the wounded aboard, and then, while under intense fire and returning fire with his captured weapon, he ran alongside the helicopter as it flew just a few feet off the ground toward the others. He got the rest of the wounded aboard, as well as the dead, except for the fallen team leader. As he raced to retrieve his body, and the classified documents the dead man had carried, he was shot in the stomach and grenade fragments cut into his back.

Before he could make his way back toward the helicopter, the pilot was fatally wounded and the aircraft crashed upside down. He helped the wounded escape the burning wreckage and organized them in a defensive perimeter. He called for air strikes and fire from circling gunships to suppress the ever increasing enemy fire enough to allow another evacuation attempt. Critically wounded, Benavidez moved constantly along the perimeter, bringing water and ammunition to the defenders, treating their wounds, encouraging them to hold on. He sustained several more gunshot wounds, but he continued to fight. For six hours.

When another extraction helicopter landed, he helped the wounded toward it, one and two at a time. On his second trip, an enemy soldier ran up behind him and struck him with his rifle butt. Sergeant Benavidez turned to close with the man and his bayonet and fought him, hand to hand, to the death. Wounded again, he recovered the rest of his comrades. As the last were lifted onto the helicopter, he exchanged more gunfire with the enemy, killing two more Vietnamese soldiers, and then ran back to collect the classified documents before at last climbing aboard and collapsing, apparently dead.

The army doctor back at Loc Ninh thought him dead anyway. Bleeding profusely, his intestines spilling from his stomach wounds, completely immobile, and unable to speak, Benavidez was placed into a body bag. As the doctor began to pull up the black shrouds zipper, Roy Benavidez spit in his face. They flew him to Saigon for surgery, where he began a year in hospitals recovering from seven serious gunshot wounds, twenty-eight shrapnel wounds, and bayonet wounds in both arms.

Hard to believe, isnt it, what this one man did? And why? Because his buddies called out to him? Because the training just took over? Because it was automatic, he was in the moment, aware of what was required of him but senseless to the probable futility of his efforts? These are the sort of explanations you usually hear from someone who has distinguished himself in battle. They really dont help us understand. They mean something, but as an explanation for that kind of heroism, they are as unenlightening to me as haiku poetry. What kind of training prepares you to do that? What kind of unit solidarity, how great the love and trust for the man to your right and your left, inspires you to the superhuman heroics of Roy Benavidez?

Next page