Copyright 2007 by John McCain and Marshall Salter

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Twelve

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com.

The Warner Books name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

ISBN: 978-0-446-19871-4

First eBook Edition: August 2007

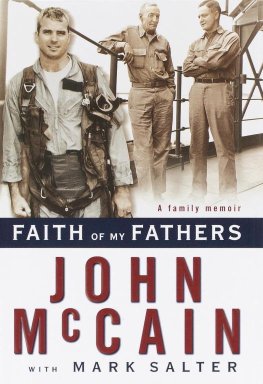

also by JOHN MCCAIN with MARK SALTER

Faith of My Fathers

Worth the Fighting For

Why Courage Matters

Character Is Destiny

For Roberta McCain and Lauralie Salter, assured and intelligent decision makers, whose example their sons have, with mixed success, tried to emulate

I knew a man who slept through the night. He had nearly reached the end. Wounded, starved, delirious, and exhausted, he commanded himself to consider his situation carefully. The sights and sounds of salvation beckoned him and must have quickened the impulse to run toward it. In the last few days of his journey, he worried that he was losing his mind. He was slipping in and out of consciousness. He had caught himself arguing loudly with a Sunday-school teacher from his childhood. Thanking God for getting him this far, he briefly mistook his own voice for another Americans. Now, he had to summon all that remained of his wits, and his formidable courage, to make the most fateful decision of his life: to make one last dash now or to wait for daylight. His choice might win a heros welcome or indefinite pain and suffering; the blessings of a wife and children or the cruelty of an angered enemy; freedom or captivity; life or death.

He chose to wait.

Two weeks earlier, on August 26, 1967, Air Force Major George Bud Day had been shot down and captured north of Vietnams DMZ. He had broken his right arm in three places, painfully sprained his knee, and battered his face when he ejected from his F-100 fighter jet. The North Vietnamese who captured him had roughly set his fractures, fashioned a crude cast for his broken arm, bound his ankles together, and put him in a hole in the ground until he could be transported north. Tough old bird that he was, Bud decided to go home instead. Late in his first night of captivity, he freed himself from the ropes, crawled out of his hole, and quietly began his trek to the other side of the DMZ and an American airfield, twenty miles or so to the south.

Over the next two weeks, he traveled at night and slept when he could during the day. He waded through rice paddies, dragged himself across jungle floors, climbed hills, crossed rivers, wandered in circles under dense jungle canopy, narrowly evaded recapture, and, once, risked exposing himself to enemy fire while floating down the Ben Hai River on two pieces of bamboo. He subsisted on dew and rainwater, a handful of berries now and then, and a couple of live frogs he swallowed out of desperation. He became ill, unable at one point to keep water down. He burned with fever. But he was tougher than most men, and braver. And he kept moving south.

Finally, near the end of the thirteenth day of his escape, he came to rest within a mile of a forward American air base. He watched helicopters and aircraft take off and land, signaled one or two unsuccessfully, and fought the impulse to run toward his countrymen as fast as a starving, half-dead man with a bum knee and a broken arm could. But he restrained himself. Given his condition and the powerful temptation posed by the prospect of imminent rescue from his miseries, his restraint strikes me as almost as superhuman as the astonishing feat of endurance and guts that had brought him so close to salvation. Of course, as I would soon come to know, Bud Day is no ordinary man.

He had the presence of mind and discipline in the most trying of circumstances to weigh the risks of hurried action. He assumed that the perimeter of the airfield was mined. And he worried that in the dark, a limping, crooked, sun-darkened scarecrow of a man hastily making his way toward the base might be mistaken for someone other than an American pilot by a wary sentry with a loaded M-1 and an aversion to taking chances. So, he concluded that he would wait for daylight to make his approach, and he lay down in the jungle for one last night.

It was a sound decision. It might have been the right one. The perimeter was likely mined, and he very well could have been mistaken for the enemy and fired upon. It was certainly a difficult decision, though. So much was at stake, and there were so many unknowns on which to base a truly existential decision. It was a very hard call.

He had made the decision not knowing if time would prove him right or wrong, not knowing anything for certain. Would he be captured in the night? Would he be alive in the morning? He knew only that he had exercised the discipline necessary to make the best decision he could. Cowardice had not restrained him, informed caution hadthat and courage, the courage to endure another night of terror and suffering. He was aware of his situation, its risks and rewards. He had weighed his prospects as judiciously as time and circumstances allowed. And he chose well.

He had chosen well from the beginning of his odyssey to its end. When almost any other man in his condition would have rejected the idea of escape as impossible, he had risked it. Not rashly or mistakenlyhe had assessed his circumstances correctly. He had not been tightly bound. He had not been kept in a cell but in a shallow, underground shelter. Perhaps, because his captors had not imagined that a man in his shape could manage an escape attempt, he hadnt been closely guarded. He was familiar with the terrain, and he had known the direction and distance to safety. He had had the cover of darkness.

He had believed in the mission. He had had confidence in his ability to accomplish it, not an irrational confidence born of conceit. He had known he had courage and stamina sufficient to overcome his injuries. He had known the time was right. His physical condition would decline with every day of captivity, and soon he would be taken north to prison. He did not act for himself alone, but for his family, to whom he wished to return. He was inspired by his duty to them and to the military code that exhorted captured Americans to escape if possible. He could see it was possible, when others would have seen the contrary.

His last decision, too, was a question of timing. Was it better to risk friendly fire and tripping a mine in the dark or to risk capture? He made a sound, informed, and hard decision that the risks of the former were greater than those of the latter. He would wait.

He had earned his freedom, fought for it, like no other man I have ever known. He should have had it.

As it turned out, he was to wait nearly six years for the freedom he had nearly grasped that night. He had risen with the dawn and made his way toward the base. In the open, several yards from the last jungle between him and safety, he was spotted by two North Vietnamese soldiers. They shouted at him to stop. He made a run for cover, and just before he reached it a bullet to his left leg brought him down. He hid in the bush as best he could. He lay still, trying not to breathe or groan from the pain, his heartbeat the only sound. He listened as his enemies tore madly through the jungle, shouting and firing indiscriminately. He lay still as one of them drew almost near enough to touch him but for a moment still could not see or hear him. And then he did.