Contents

Foreword

The Myth of McCain

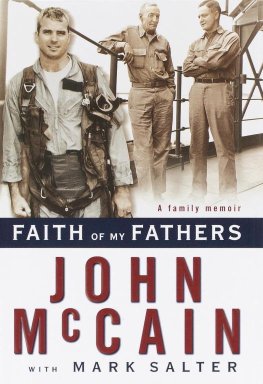

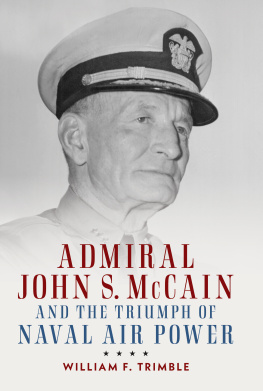

O ver the course of a career, most nationally prominent politicians, particularly those who choose to seek the White House, can expect ups and downs in their treatment by the press. While some are looked on more favorably than others, most of the key figures in national politics will see times when they are hailed as victors and praised for their strengths, and times when they are derided as losers and pilloried for their weaknesses. But in recent years, there has been one exception to this rule: John McCain. While other politicians are examined with a cynical eye, McCain and his admirers in the media have cooperated to construct a shimmering image of the senator from Arizona, one that has propelled him to the heights of American politics. McCain, as he has been presented to the public, is a straight-talking maverick, a war hero standing astride the parties and untroubled by political calculations.

As the forthcoming chapters will show, no other modern politician has received as much favorable press as John McCain has in the past decade, a period that has seen him go from a relative unknown to the man that The Almanac of American Politics calls the closest thing our politics has to a national hero.1 While some politicians might get nearly as much attention, and a few others (such as Chuck Hagel or Richard Lugar) are privileged with steadily laudatory press, McCain stands alone in the combination of his high profile in the media and the overwhelmingly positive tone of the coverage that the press gives him.

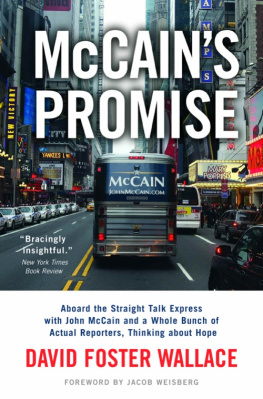

But calling McCains coverage positive does not begin to convey the complexity of his singular status in the media. In a hundred ways, the rules are simply different for McCain. Indeed, when writing about McCain, journalists offer a unique brand of praise. Here are a few of the things hard-bitten reporters said about McCain during his 2000 run for the presidency:

A man of unshakable character, willing to stand up for his convictions.2 (R. W. Apple, New York Times)

An original, imaginative, and at times inspiring candidate.3 ( Jacob Weisberg, Slate)

Mr. McCain is running as the blunt anti-politician who wont lie, who wont spin.4 (Alison Mitchell, New York Times)

While most candidates talk up their chances, McCain engages in anti-spin.5 (Howard Kurtz, Washington Post)

He rises above the pack in admitting its not all the other partys fault. Hes eloquent, as only a prisoner of war can be.6 (David Nyhan, Boston Globe)

McCain conveys a great sense of vigor, a sense that anything can happen on his campaign.7 ( Roger Simon, U.S. News & World Report)

Theres something authentic about this man.8 (Mike Wallace, 60 Minutes)

Basically just a cool dude.9 ( Jake Tapper, Salon)

This samplingall from the campaign season, when reporters tend to be more cynicalonly skims the surface. In story after story, the media portrayedand continue to portrayJohn McCain as a larger-than-life anti-politician, unbeholden to special interests and driven not by ambition but by a sense of duty. Such was the rapport that developed between McCain and the media in 2000 that McCain staffers began to call the media their base. As Michael Lewis, a frequent magazine contributor and bestselling author, wrote about McCain in 1997, I became used to opening the morning paper and finding McCains quotes on the front page and his opinions echoed on the editorial page. It was a testament to the growing distrust between the press and the more ordinary politicians. Here was a Republican Senatora red meat, pro-life, strong-army kind of guyand yet somehow he had become the preferred source of the putatively liberal media.10

Lewis may have been one of the first reporters to turn his wordsmithing talents to the elevation of John McCain the politician (R. W. Apple also wrote some of the first tributes to McCain, in the New York Times), but he was hardly the last. David Broder and David Ignatius of the Washington Post, Howard Fineman of Newsweek, Joe Klein of Time (who described McCains 2000 campaign as containing hints of what politics might becomeif were lucky11), and Chris Matthews of MSNBC would have to be counted among McCains most enthusiastic current boosters in the major media. Although these men may be more demonstrative in their admiration for McCain, that admiration is evident in nearly all the coverage McCain has received, particularly since his campaign for the 2000 Republican nomination for president.

The result has been a virtually indestructible media creation: the Myth of McCain. We call it a myth not to assert that all the themes that run through the coverage of McCain are plainly false. Rather, we use the term according to its dictionary definition, meaning the foundational set of precepts on which a belief system is based. Even as his 2008 campaign experienced some early stumbles and he did things that seemed to call into question the foundations of his image, the Myth of McCain remained intact. The myth consists of the following ideas:

John McCain is a maverick.

John McCain is a moderate.

John McCain is a straight talker.

John McCain is a reformer.

John McCain doesnt do things just because theyre politically expedient.

Just about all you need to know about John McCains character is that he showed courage as a prisoner of war in Vietnam.

John McCain has too much integrity to use his war record to his political advantage.

Some of these ideas have a basis in reality but have been wildly exaggerated; others are simply false. What is incontrovertible is that the press has continually foregrounded them at the expense of a more rounded and accurate portrait of McCain.

Even when early problems on the 2008 campaign trail (such as lackluster fund-raising in the first quarter of 2007) resulted in some uncharacteristically critical coverage for McCain, the elements of the myth remained intact. What that period of more critical press showed was that even McCains negative coverage is more positive than that which other candidates receive. Unlike other candidates, McCain finds that momentary controversies (as when he responded to a question about Iran by singing Bomb bomb bomb, bomb bomb Iran to the tune of Barbara Ann) are presented in isolation, unconnected to any alleged character flaws.

The contrast with other candidates is striking. When Mitt Romney makes a seemingly exaggerated claim about his history as a hunter, reporters connect the statement to doubts about whether Romney is genuine and sincere. When John Edwards gets an expensive haircut, reporters question whether he is a true populist and sufficiently substantive. The allegedly revealing incidents are contextualized by other similar incidents from the candidates past and then brought up again and again in the future. In other words, the negative press of the moment is linked to what we are told are the candidates significant flaws, the deficiencies in their character that raise questions about whether they are fit to be president.

Not so for John McCain. The very idea that McCain might have deficiencies of character that relate to his fitness to be president is never contemplated. The consequence is that a spate of bad coverage, whether over a temporarily struggling campaign or an intemperate remark, does nothing to undermine his prospects for a future comeback. Others find their worst moments replayed over and over, used to indict their character and highlight their flaws. But the John McCain portrayed in the media has no character flaws. He may say something dumb or be down in the polls, but his fundamental virtue is never questioned. If he is down, he is therefore always poised for a revival. If he panders, he will resume his admirable candor any dayas an April 2007 column by David Broder of the

Next page