An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2019 by Steven M. Gillon

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

DUTTON and the D colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Gillon, Steven M., author.

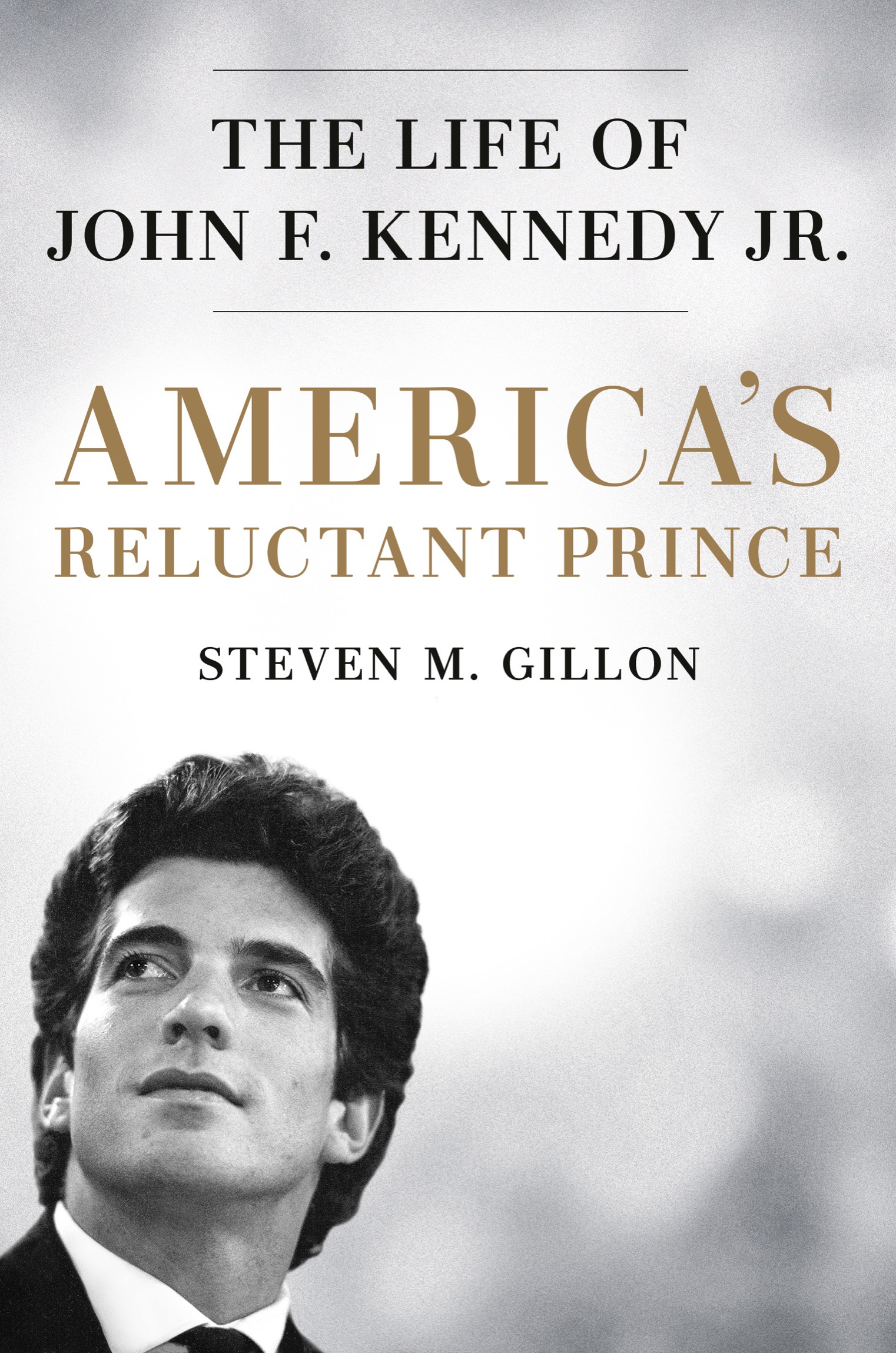

Title: Americas reluctant prince : the life of John F. Kennedy Jr. / Steven M. Gillon. Other titles: Life of John F. Kennedy Jr.

Description: First edition. | New York : Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2019014938 (print) | LCCN 2019017483 (ebook) | ISBN 9781524742393 (ebook) | ISBN 9781524742386 (hc)

Subjects: LCSH: Kennedy, John F., Jr., 19601999. | Children of presidentsUnited StatesBiography. | CelebritiesUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC E843.K42 (ebook) | LCC E843.K42 G55 2019 (print) | DDC 973.922092 [B] dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019014938

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Version_1

To Mom and Dad, with love, as always

CONTENTS

PREFACE

DONT BE JOHN KENNEDY

I met John F. Kennedy Jr. in the spring of 1981, when I was a twenty-five-year-old graduate student. He was a twenty-one-year-old sophomore history major at Brown University, and I was the teaching assistant in a class on twentieth-century American political history. Our friendship got off to an inauspicious start. Before the semester began, the professor, renowned historian James T. Patterson, told me that he wanted his assistants to deliver a lecture as preparation for a teaching career. I had applied to the PhD program in American civilization to study early American history, so I was not as familiar with the recent past. I had, however, always been fascinated with the 1960s, and the Kennedy presidency in particular. So I decided to give a critical lecture on JFK and civil rights.

I had been vaguely aware that John was on campus and had seen him several times, usually surrounded by a gaggle of giddy girls. It never occurred to me that he would take a class that would deal with his fathers presidency. On the first day, I stood in the back of the room handing out syllabi to students pouring into the Manning Chapel classroom. Looking over the line of students, I spied a large mane of unruly brown hair slowly approaching me. Please, no, I thought to myself. Dont be John Kennedy. It was bad enough that I would be speaking in public for the first time and doing so in front of the professor I wanted as my advisor. Now I faced the prospect of criticizing a president while his son looked on. A few seconds later, John approached, reached for the syllabus, thanked me, and then sat down in the back of the room.

I would have tried switching my topic had I thought Patterson would allow it. But I would need a better excuse than I am afraid to give a lecture about President Kennedy while John is in the class. That statement would surely have marked the end of my graduate career, and rightly so.

My talk was scheduled for March, so for the next few months, I labored to write and rehearse the lecture. It took about five weeks to write the talk, and then I spent another four weeks practicing it. Every day, I would recite the entire fifty-minute lecture before breakfast, after dinner, and again before I went to sleep. I had a lot on the line. Not only would I be giving a public lecture for the first timeand doing so in front of more than a hundred bright Brown undergraduatesbut also I was auditioning for a spot as one of Pattersons PhD students. Oh, and then there was John, although I must confess, Patterson scared me more than John.

At 10:55 A.M. on the day of my lecture, I marched into the hall and took my position behind the podium, hands tucked safely in my pockets so students would not see them shaking. Professor Patterson took a seat in the middle of the room. Looking around, I took some comfort in seeing that John was absent, a not-uncommon occurrence. But just as I was about to start, the back door swung open and in he walked. Students have a natural tendency to sit as far away from the professor as possible, so the back rows were full. John kept moving forward until he plopped down in the seat directly in front of me.

John and I sat only a few feet apart that day, but we came from vastly different worlds. I grew up in a working-class family outside Philadelphia. I had been a mediocre student for most of my life but finally turned things around in college, earning good enough grades to get accepted at Brown. Education has often been the pathway to the American Dream, and that was certainly true in my case.

Getting into Brown was my big break. There was no way I was going to screw up this opportunity.

The first line of my lecture, which I can still recall almost four decades later, read: President Kennedy was a pragmatist who did not impose moral solutions on problems. Simple enough. Yet somehow my well-rehearsed words escaped me the moment I needed them most. I stood in front of the room paralyzed by fearfear of the one hundred students in the class, fear of my intimidating professor, and, perhaps, fear of giving a lecture about a man while his son sat a few feet away. My first public lecture thus began with a succession of Ahs and Ums. My mind had gone blank. I thought, Just look down and read the words on the page in front of you.

During times of crisis, some people are able to reach deep down inside themselves and find a vast reservoir of strength. I am not one of those people. I hyperventilate. I sweat. I grow more and more anxious. I finally looked down at my notes, but by this point everything had grown fuzzy. What in the world was I going to do? Either I said something soon, or I would be forced to run out of the room humiliated and resign myself to a short life doing manual labor.

I kept repeating to myself, Say something. Anything. So I did. President Kennedy, I began, President Kennedy. President Kennedy had no moral scruples. I have absolutely no idea where that came from, but that was what came out. As soon as the words left my lips, I realized I was in trouble. I glanced down at John, who glared up at me. Then a student in the back of the room, who was too far away to see the look of terror on my face, must have assumed that it was all a joke. She laughed and the entire class joined in. That laugh saved my career. With the ice broken, I went on to finish the lecture. I criticized JFK for being too slow to embrace the civil rights cause but noted that he eventually did, and in a famous June 11, 1963, address, he became the first president in history to refer to the civil rights movement as a moral cause. Before he left the room, John came up, shook my hand, and said, Great lecture.