HIGH PRAISE FOR

ESTER and RUZYA

H OW M Y G RANDMOTHERS S URVIVED

H ITLERS W AR AND S TALINS P EACE

A journalists memoir of her grandmothers also paints an eloquent portrait of two totalitarian powers, the havoc they wrought, and the countless burdens they imposed on ordinary families A masterful chronicle of dark and dangerous years, and a distinguished addition to the history of totalitarianism.

Kirkus Reviews

A loving memoir of two grandmothers that offers a penetrating look at two killer regimes. Masha Gessens wonderful book portrays human beings trying to live justly when there is virtually no way to do so.

William Taubman, Pulitzer Prizewinning author of

Khrushchev: The Man and His Era

This blend of historical depth with personal experience is a powerful mix, illuminating how family and friendship can grow in even the darkest eras.

Publishers Weekly

A saga of two fascinating Russian-Jewish women making ends meet, making love, making homes, making agonizing compromises in the most terrible times of the twentieth centurywitty, colorful, tragic, seething with life and character, it is a little classic of storytelling.

Simon Sebag Montefiore, author of

Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar

This is a deeply moving account of what it meant to be a Jew under Hitlers rule and, equally brutal, Stalins rule. Masha Gessen, a talented writer with a human touch, has brilliantly used her grandmothers as a way to bring to life a grim era of East European history.

Daniel Schorr, senior news analyst for National Public Radio

Masha Gessen has written an indispensable history of Soviet Jews as seen through the eyes of two unforgettable womenher grandmothers. The scope and complexity of their characters rivals anything you will find in contemporary fiction. Their lives, underscored by hardship, compromise and hope, are rendered both with a granddaughters love and a journalists insight. A beautiful book.

Gary Shteyngart, author of

The Russian Debutantes Handbook

Ester and Ruzya is an example of whats best in Russias literary traditiona beautifully written personal story with universal significance.

Nina Khrushcheva, Professor of International Affairs,

New School University

Beautifully written and deeply felt, Masha Gessens Ester and Ruzya tells the story of the two totalitarian regimes that reigned in twentieth-century Europe from a completely fresh perspective. Gessens description of the compromises people made to survive should force those of us living in a luckier era to think harder about what we mean by morality.

Anne Applebaum, Pulitzer Prizewinning author of

Gulag: A History

ESTER AND RUZYA

A Dial Press Trade Paperback

PUBLISHING HISTORY

Dial Press hardcover edition published November 2004

Dial Press trade paperback edition / November 2005

Published by Bantam Dell

A Division of Random House, Inc.

New York, New York

All rights reserved

Copyright 2004 by Masha Gessen

Interior photograph of Ashkhabad by Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin Gorski, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

Interior photograph of Bialystok, courtesy of Tomek Wisniewski, www.szukamypolski.com

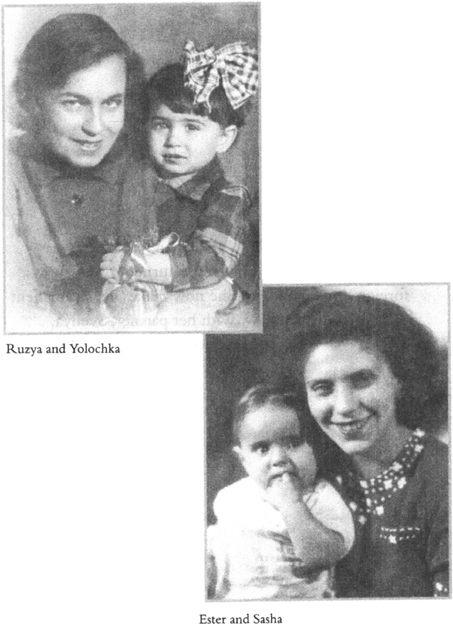

All other interior photographs used by permission of the author

Author photo by Svenya Generalova

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2004045472

Dial Press is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc., and the colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

eISBN: 978-0-307-48438-3

www.dialpress.com

v3.1_r1

C ONTENTS

P ART O NE

DREAMS, 19201941

P ART T WO

WAR, 19411942

P ART T HREE

SURVIVAL, 19421943

P ART F OUR

JAKUB, 19411943

P ART F IVE

SECRETS, 19431953

P ART S IX

STALINS FUNERAL, 19531959

P ART S EVEN

FAMILY, 19581987

P ROLOGUE

M ARCH 1991

I was not traveling light, or lightly. I was terrified, which was to be expected after ten years (exactly) in exile: I admitted to being scared that I might not be allowed to leave the Soviet Union, but this was a red herring of a fear. I claimed not to know what had frightened me so much that I squeezed my companions hand until her knuckles turned white as we touched down. I feared I would recognize this country and I feared I would not know it; I feared I would dislike it and I feared I would love it; I feared that my clear and certain opinions about the world and Russia in general and about my relationship to them in particular would be turned inside outwhich, of course, was precisely what was about to happen.

What did I see when I imagined Russia? Snapshot memories of a few buildings and streets. The interiors of my grandmothers apartments. My parents drawn faces when they explained to me why we had to leave the country where I was born, and their growing exhaustion as they took each of the endless steps required to emigrate. February 18, 1981: a day that ended in the gray early morning, as the plane slowly gained altitude over an expanse of snow. I remembered our relatives, eyes red from sleeplessness and crying, lined up in two crowded rows against the chrome barrier that marked the border zone at Moscows Sheremetyevo-Two Airport, watching two customs officers go through our belongings, packed into our emigrants suitcasescheap cardboard affairs designed to withstand exactly one journey, one way. I ran back to hand one of my aunts my drawing box, barred by customs. I ran back again to take a drag off another aunts cigarette. I was fourteen, but this was the most difficult day of my life. We finally stepped through customs, sideways and backward so as to keep looking at their faces, receding now. They waved. Two-thirds of the way to passport control, just before their features became indistinguishable, my mother drew my head close and whispered, Look at them. You will see all of them again, except Great-grandmother Batsheva. Look at her. What she said was absurd: everyone knew there would be no return and we would never see any of them. But she turned out to be almost exactly right: I saw all of them again, except for Great-aunt Eugenia, who died later the same year, and Great-grandmother Batsheva, who died in 1987.

As the plane began its descent now, I imagined they would be right there, pushed up against the same chrome barrier, unmoved and unchanged save for being ten years older. I tried to make out their faces in my memory, but I visualized, instead, the face of an actor I had seen in a recent Russian film, or the shadow of an old photograph. I studied every face once I stepped into the terminal, and I suspected every one of being my relative. But I saw them once I got through passport control: they really were there, behind the chrome barrier, and I recognized them immediately.