Dedicated with thanks and reverence to the Four Horsemen (or Horsepeople) in my life without whom very little good would have happened.

and MARTIN SPENCER, Paradigm agent provocateur, whose belief in my work led me to this place.

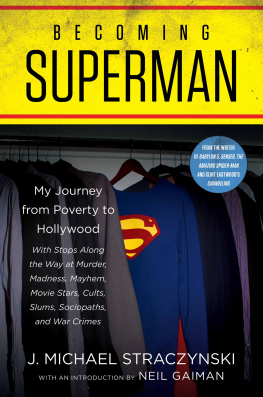

I properly met Joe Straczynski in, I believe, January of 1991. He was hosting the Hour 25 radio show on KPFK-FM Los Angeles, and Terry Pratchett and I were on the show that night, to talk about our book Good Omens. Before Joe arrived, the station boss came and warned Terry and me that she knew how we British people liked to swear on the radio, and that no swearing on our parts would be tolerated. (We asked if it was all right to mention a fictional book in Good Omens called the Buggre Alle This Bible, and she went away and checked with the Authorities and said it was.) Wed neither of us ever sworn during any radio interview before, but were now terrified that we would, and we did our interview convinced that at any moment a fit of something resembling Tourettes syndrome might overtake us. I remember that it was late at night in a dim-dark studio, and when Joe went over from talking to us to taking questions from callers, at least one of the voices at the other end of the line made no sense at all, the words were random and confused, and Joe cut him off, but kindly, and we carried on talking.

I say properly met, because I think I had already met Joe before that, at dinner with Harlan Ellison, but maybe all those dinners with Harlan were afterward. And thats the hell of memoirs and autobiographies: you are dealing with what you remember, and what you remember is fallible and its unreliable and sometimes its simply wrong, and yet its still all you have to go on.

Weve worked together once: Joe asked if I would write a script for Babylon 5 for him before the show began, and each season I would apologize because my plate was filled with Sandman and with the original Neverwhere TV series, and then Joe got to his final season, and I said yes, because Sandman and Neverwhere were done and I had the time, and in 1998 I wrote an episode called The Day of the Dead for him. Joe was, for the record, the easiest and sanest television executive Ive ever written for: he was writing the entire show himself (except for my episode), and overseeing it, and doing all this without giving any indication of breaking a sweat.

So Ive known Joe for almost thirty years. His hair has changed in that time (long ago it was darker and there was significantly more of it), but from the hairline down hes still very much the same man I met in that voice-haunted radio studio late one night. Hes decent, and hes good-hearted; he works harder than anyone Ive met in film and TV; hes sane and hes sensible, accessible and wise. Which, you would think, would mean that the autobiographical volume you are reading would be as dull as insurance policy small print: people are as interesting as they are flawed, their stories as fascinating as the obstacles they encounter on the way.

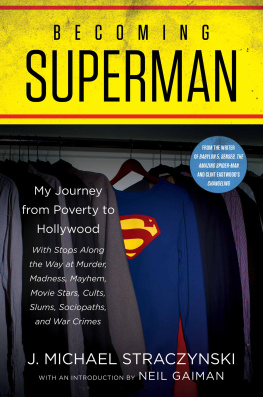

In Joes case, as you read his story you also start to realize the pressure and the force that created the ferociously hardworking and ethical entity that he is: you understand not only what he was reacting against, but the pressure that he was under. Superman, one of Joes inspirations, could squeeze coal into diamonds. I was never convinced that it would work in real life, the whole coal-to-diamonds thing, suspecting that if you werent Superman and you squeezed a lump of coal really hard, youd get coal dust; but the pressures of Joes life and childhood, the people who surrounded him, gave him something and someone not to be, gave him something to transcend, something to survive. Most people would have become coal dust. He didnt.

The childhood we read about here is like an iron key winding up the clockwork that might so easily have destroyed Joe or turned him into a monster: instead it gave him power and a place to stand, and, most of all, a willingness to learn.

We follow him through several careers, and in each career he learns how to do it, how to set out and make something happen that ought, by any stretch of the imagination, to have been impossible. Its his willingness to learn, his quiet persistence, and his willingness to do the work that are his superpowers. He has become a diamond.

And now he is finally willing to share.

Neil Gaiman

London

June 2017

I celand. March 14, 2014.

An hour earlier and a thousand feet nearer the ground we had been on a narrow strip of road bordered on both sides by a seemingly endless expanse of black volcanic rock and green moss, the air crisp but not cold. Then we started the long climb up a steep mountain, and within minutes the sky was swallowed by snow. The road turned from black to the brittle white of hard packed ice, then disappeared altogether. The world had no edges, the sky no shape, the sun no particular direction. We were inside a snow globe, with nothing before, behind, or beside us.

We climbed out to better experience the whiteout: location managers, production coordinators, directors, producers, and writers, myself among the latter two categories. We were warned to stay close: anyone walking more than twenty feet from the caravan would be lost to sight.

Iceland was the first stop in our round-the-world tour to scout locations for Sense8, a Netflix series I had written, created, and was producing with the Wachowskis. From here the show would travel to Mexico City, San Francisco, Seoul, Chicago, Berlin, Nairobi, and London.

The story that brought us here concerned a young woman who gives birth in the middle of the frozen tundra miles from civilization. Stranded after a car wreck, alone and on foot, the odds of her or her infant surviving the intense cold are nearly zero, but she keeps walking anyway, refusing to go down without a fight. Desperation and tears in the cruel bitter wind. Blood on snow.

Wed come to determine if this particular mountain would suffice, but someone had apparently backed up a U-Haul and taken it away before we arrived, leaving only a curtain of white void that stretched to infinity.

We should get off the mountain before it gets dark, the location manager said, while we can still see the road.

Road, hell, someone said in reply. We should go while we can still see the mountain.

As I climbed back into the van I paused to look out at the white void, two thousand seven hundred miles from where I began my journey in Paterson, New Jersey. And it occurred to me that the only thing more improbable than being on this road was the longer and considerably darker road that brought me there: the mistakes and wrong turns, the tragedies and lies, the wise and poor decisions... and the secrets Id kept about myself, my family, and my past, afraid of what the world would think.

The whisper of things left long unsaid echoed out at me from the void. We know who you are. Who you really are. You may be able to fool everybody else, but you cant fool us. And as long as were out here, where you cant reach us, you will never be truly free.

Writers tell stories. Its what we do. Its what Ive done my whole life. But theres one story Ive never told, trained into silence by people who wanted to make sure that my familys secrets remained secret.

And theres only one appropriate response when you discover youre afraid of something.

You get up and you