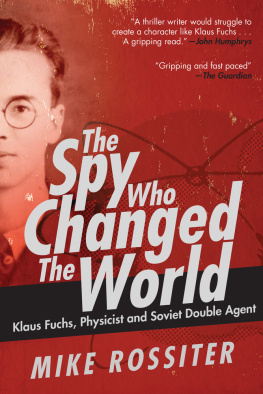

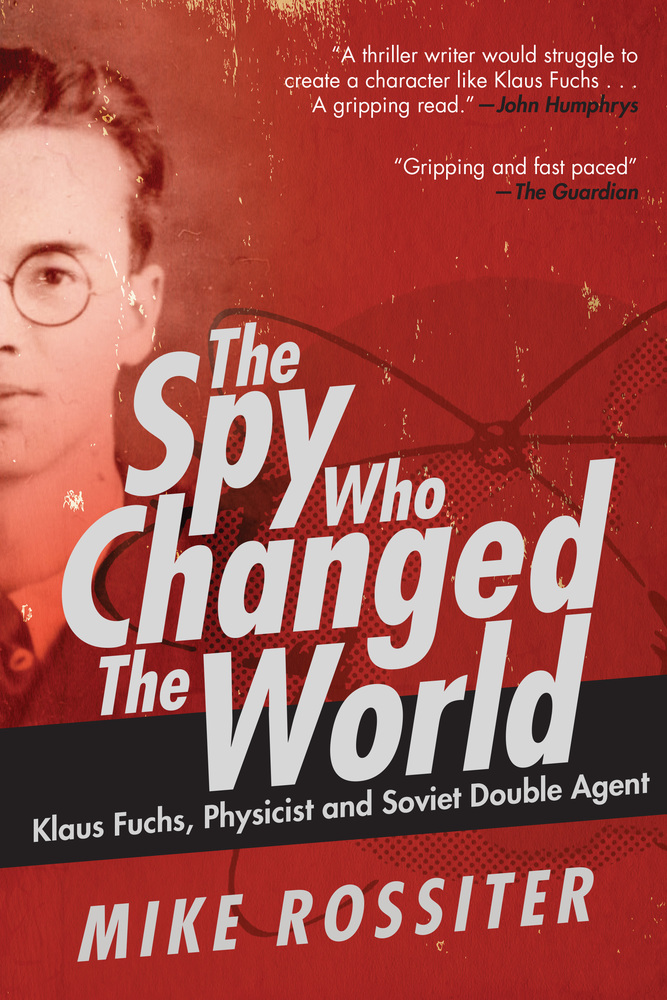

Copyright 2015, 2017 by Mike Rossiter

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Rain Saukas

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-2674-1

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-2675-8

Printed in the United States of America

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I could not have written this book without the significant assistance of several people. The archive research was not limited to the United Kingdom, and I would like to thank Christina Overmeyer for the help she gave me researching material in Germany. She spent many hours negotiating with the BStU, the archive of files maintained by the East German Secret Police in Berlin, and several days translating the findings of the a rchivist a ssigned to the case, Frau Gudrun Wenzel. Christina also met me in Berlin for a search through the records of the Bundesarchiv and then translated the results. This was a reversal of roles for us, because I first met Christina as a young au pair looking after my sons and trying to improve her English, and she has now just completed her Masters at Beyreuth University.

A successful search of several archives in Moscow for material on Klaus Fuchs and Grete Keilson was carried out for me with great enthusiasm and initiative by Margarita Bolytcheva, a young journalism student at Moscow University, who has a great future ahead of her I am sure. The results of this, and a variety of other Russian source material gathered from various libraries, was translated for me by Angela Spindler-Brown, with whom I have worked over the years on many Russian adventures as a translator, archive researcher and producer. My original visit to the Kurchatov Institute would have been impossible without her, and we went on subsequently to visit chemical warfare camps and other KGB archives for further documentaries. I am very lucky to be able to call on the assistance of all three people.

The book would not have been published without the help and advice of my agent Luigi Bonomi, whom I once saw referred to in print as cuddly. I am not sure of that, and I value more his honesty and optimism. Simon Thorogood, at Headline, commissioned me to write The Spy Who Changed the World and has not only guided it through the publishing process, but sat and listened over coffee when I thought the project was getting out of hand. The copy editor Brenda Updegraff has gone over my text, made it readable, pointed out my mistakes, explained why some sections were not really working and struggled under a very tight deadline to get the book into decent shape. I am lucky to be able to work with these three people as well.

I finally have to thank my wife Anne, and my two sons Max and Alex, who are by now immune to the problems of living with a writer. Im lucky to have them in my life.

This is a story that contains some difficult scientific concepts and I have tried to simplify them as much as possible to help the flow of the narrative. I am not a nuclear physicist and I have probably made some mistakes; these and any other errors that may be noticed are my responsibility, as of course are the opinions and interpretations contained in the book.

Mike Rossiter, March 2014

Contents

Introduction: A Trip to Moscow

J ust how big a spy was Klaus Fuchs? Fuchs was arrested and jailed in Britain in 1950 for passing secrets about atomic research to the Soviet Union. At the time, Fleet Street claimed that he was a traitor who had sold the secrets of the atom bomb to the Russians. But as the initial storm of hysteria passed on to other crises and other spies, hard facts about the Fuchs case seemed elusive, despite investigation by writers more serious and authoritative than journalists in the popular press. The well-known author Rebecca West wrote a lengthy expos of Fuchss treachery in The Meaning of Treason. Two years after the trial a book about the atom spies, The Traitors by Alan Moorehead, was published and it turned out that the author had been selected and provided with enormous help by the British Security Service, MI5. Then a few years later the eminent historian Margaret Gowing turned her attention to Fuchs as a small part of her exhaustive volumes on the history of Britains nuclear programme.

Despite all this work, facts seemed thin on the ground. True, Fuchs was a German scientist who had been a refugee from Nazi Germany, he had worked on atomic research, and his sentence of fourteen years imprisonment had been based on his own confession. The rest seemed contradictory. Was he, as the official history of Britains nuclear programme implies, a second-rate scientist merely handing over the work of others? Did he have any secrets to sell? Some academics suggested that the Russians would have built their bomb anyway, whether Fuchs had given them a few pointers or not. What sort of a person was he? Was he an evil conspirator or a slightly repressed man, nave, divorced from reality, who gradually came to see the error of his ways? Was it true, as the MI5-sponsored book claimed, that their chief interrogator, William Jim Skardon, skilfully probed the psychology of Fuchs and persuaded him to confess?

I thought that I would get to the bottom of some of these questions several years ago, when I went to Moscow to interview someone who was intimately connected to Fuchss work as an atomic scientist. My appointment was with Academician Georgi Flerov, a man who had played a significant role in the first Soviet atomic bomb. It was Flerov who had written a letter to the Soviet chiefs of staff in 1942 suggesting that a nuclear weapon was possible, that it was likely that scientists in the United States, Britain and Germany were already working on this question, and that the Soviet Union should start its own programme urgently.

Flerov had later travelled to Berlin, in May 1945, shortly after the defeat of Nazi Germany, dressed in the uniform of a colonel in the NKGB,on the Nazi atomic programme during the war and arranging for them to go to the Soviet Union. It was not an easy invitation to refuse. Later, he had been the last scientist to leave the test tower when the first Soviet nuclear weapon was detonated.

It wasnt easy to get to see Flerov. I had first written to the Soviet Academy of Sciences, without any response. But change was in the air of the Soviet Union: Mikhail Gorbachev was in charge and the policy of openness had been announced. Towards the end of 1988, I received a telephone call from a woman at the French Embassy in London, in the scientific attachs office. She told me that she had a message from Academician Flerov. He would be staying at a hotel and spa in Granville, on the Normandy coast, recuperating from a hip operation. Apart from the telephone number of the hotel, there was nothing more she would tell me.

Next page