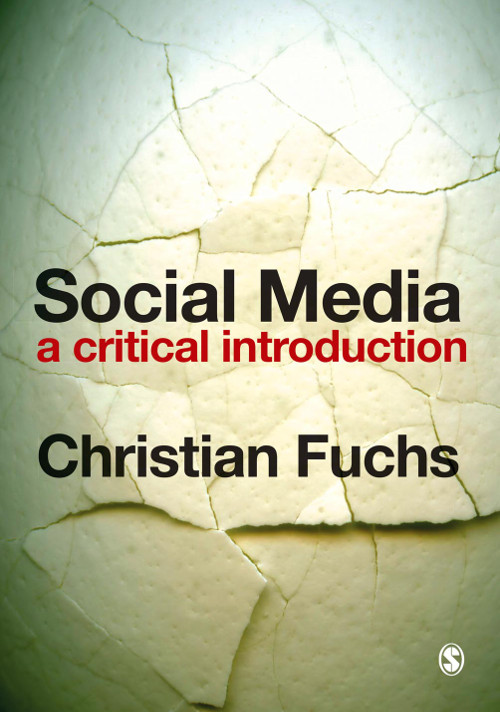

Christian Fuchs 2014

First published 2014

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, this publicationmay be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or byany means, only with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction,in accordance with the terms of licences issued by theCopyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerningreproduction outside those terms should be sent tothe publishers.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013939264

British Library Cataloguing in Publication data

A catalogue record for this book is available fromthe British Library.

ISBN 978-1-4462-5730-2

ISBN 978-1-4462-5731-9 (pbk)

SAGE Publications Ltd

1 Olivers Yard

55 City Road

London EC1Y 1SP

SAGE Publications Inc.

2455 Teller Road

Thousand Oaks, California 91320

SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd

B 1/I 1 Mohan Cooperative Industrial Area

Mathura Road

New Delhi 110 044

SAGE Publications Asia-Pacific Pte Ltd

3 Church Street

#10-04 Samsung Hub

Singapore 049483

Editor: Mila Steele

Editorial assistant: James Piper

Production editor: Imogen Roome

Proofreader: Leigh C. Timmins

Indexer: Martin Hargreaves

Marketing manager: Michael Ainsley

Cover design: Francis Kenney

Typeset by: C&M Digitals (P) Ltd, Chennai, India

Printed in Great Britain by Henry Ling Limited at

The Dorset Press, Dorchester, DT1 1HD

What is a Critical Introduction to Social Media?

Key questions

What is social about social media?

What does it mean to think critically?

What is Critical Theory and why is it relevant?

How can we approach Critical Theory?

Key concepts

Social media

Marxist theory

Critical theory

Critical political economy

Overview

What is social about social media? What are the implications of social media platforms such as Facebook, Google, YouTube Wikipedia, Twitter, for power, the economy and politics? This book gives a critical introduction to studying social media. It engages the reader with the concepts needed for critically understanding the world of social media with questions such as:

What is social about social media?

How meaningful is the notion of participatory culture for thinking about social media?

How useful are the concepts of communication power and mass self-communication in the network society for thinking about social media?

How does the business of social media work?

What is good and bad about Google, the worlds leading Internet platform and search engine?

What is the role of privacy and surveillance on Facebook, the worlds most successful social networking site?

Has Twitter brought about a new form of politics and democracy and a revitalization of the political public sphere?

What are the potentials of WikiLeaks, the worlds best-known online watchdog, for making power transparent?

What forms and principles of collaborative knowledge production are characteristic for Wikipedia, the worlds most widely accessed wiki-based online encyclopaedia?

How can we achieve social media that serve the purposes of a just and fair world, in which we control society and communicate in common?

This book introduces a theoretical framework for critically understanding social media that is used for discussing social media platforms in the context of specific topics: being social ().

Social Media and the Arab Spring

2011 was a year of protests, revolutions and political change. It was a year where people all over the world tried to make their dreams of a different society reality. Wael Ghonim is the administrator of the Facebook page We are all Khaled Said. He says that this page and other social media were crucial for the Egyptian revolution: I always said that if you want to liberate a society [...] if you want to have a free society. [...] This is Revolution 2.0. [...] Everyone is contributing to the content. Technology analyst Evgeny Morozov, in contrast to Ghonim, says that social media do not bring about revolutions: the talk of Twitter and Facebook revolutions is a naive belief in the emancipatory nature of online communication that rests on a stubborn refusal to acknowledge its downside (Morozov 2010, xiii). Pointing, clicking, uploading, liking and befriending on Facebook would be slacktivism feel-good online activism that has zero political or social impact. It gives those who participate in slacktivist campaigns an illusion of having a meaningful impact on the world without demanding anything more than joining a Facebook group (Morozov 2009). For Morozov (2013, 127), Ghonim is a man who lives and breathes Internet-centrism an ideology that reduces societal change to the Internet.

Social Media and the Occupy Movement

2011 was also the year in which various Occupy movements emerged in North America, Greece, Spain, the United Kingdom and other countries. One of their protest tactics is to build protest camps in public squares that are centres of gravity for discussions, events and protest activities. Being asked about the advantages of Occupys use of social media, respondents in the OccupyMedia! Survey said that they allow them to reach a broad public and to protect themselves from the police (for the detailed results see: Fuchs 2013):

As much as I wish that occupy would keep away from a media such as Facebook it got the advantage that it can reach out to lots of people that [...] [are] otherwise hard to reach out to (#20).

All of these social media [...] Facebook, Twitter etc. helps spread the word but I think the biggest achievement is Livestream: those of us who watch or participate in change can inform other streamers of actions, police or protest moving from one place [...] to another. That saved many streamers from getting hurt or less arrests (#36).

At the same time, the respondents identified risks of the use of commercial social media:

Facebook is generally exploitative, and controls the output of Facebook posts, the frequency they are seen by other people. Its a disaster and we shouldnt use it at all. But we still do (#28).

There have been occasions where the police seemed to have knowledge that was only shared in a private group and/or text messages and face-to-face (#55).

Events for protests that were created on Facebook, but not organized IRL [in real life]. Many participants in calls for protests on Facebook, but at least 70% of them [dont] [...] show up at the actual demonstration (#74).

Twitter has been willing to turn over protestors tweets to authorities which is a big concern (#84).

Censorship of content by YouTube and email deletions on Gmail (#103).

Yes, my Twitter account was subpoenad, for tweeting a hashtag. The supboena was dropped in court (#238).

Facebook = Tracebook (#203).

Unpaid Work for the Huffington Post

Next page