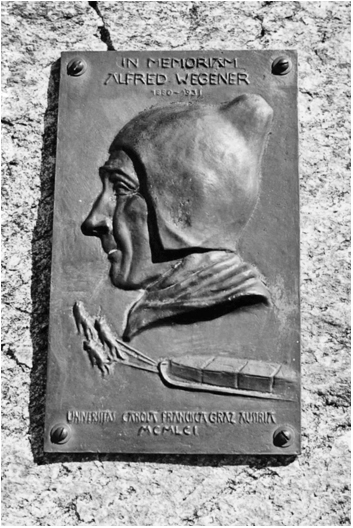

A LFRED W EGENER

Alfred Wegener

Science, Exploration, and the Theory of Continental Drift

MOTT T. GREENE

J OHNS H OPKINS U NIVERSITY P RESS Baltimore

2015 Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published 2015

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Greene, Mott T., 1945

Alfred Wegener : science, exploration, and the theory of continental drift.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4214-1712-7 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4214-1713-4 (electronic) ISBN 1-4214-1712-X (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 1-4214-1713-8 (electronic) 1. Wegener, Alfred, 18801930. 2. GeophysicistsGermanyBiography. 3. Continental drift. I. Title.

QE511.5.G74 2015

551.1'36092dc23

[B] 2014039517

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936 or specialsales@press.jhu.edu.

Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever possible.

To my wife

J O L EFFINGWELL

Contents

Preface

This is a book about the life and scientific work of Alfred Wegener, whose reputation today rests with his theory of continental displacements, better known as continental drift. Wegener proposed this theory in 1912 and developed it extensively for nearly twenty years. His book on the subject, The Origin of Continents and Oceans , went through four editions and was the focus of an international controversy in his lifetime and for some years after his death. It was translated into English, French, Italian, Spanish, Swedish, Russian, and Japanese.

Wegeners basic idea was that many (otherwise) intractable problems and puzzles of the earths history could be solved if one supposed that the continents moved laterally, rather than supposing that they remained fixed in place. Wegener worked systematically over many years to show in great detail how such continental movements were plausible and how they worked, using evidence and results from a large number of sciences: geology, geodesy, geophysics, paleontology, climatology, and paleogeography.

Wegeners ideathat the continents moveis at the heart of the theory that guides the earth sciences today: plate tectonics. This theory is in many respects quite different from Wegeners proposal, in the same way that modern evolutionary theory is very different from Darwins original ideas about biological evolution. Yet plate tectonics is a descendent of Alfred Wegeners theory of continental drift, in quite the same way that modern evolutionary theory is a descendent of Darwins theory of natural selection.

Given that Wegener is the progenitor of a major theory governing a modern science, it comes as something of a surprise to discover that no scholarly biography treating his life and scientific work has ever been attempted. His wife wrote and published an appreciative memoir in 1960, and since then there has been a good and useful popular biography by Ulrich Wutzke, the worlds leading authority on the provenance and location of Wegeners papers. Wutzkes book, however, contains almost no discussion of Wegeners scientific work and concentrates instead on Wegeners exciting career in polar exploration. Its major narrative line follows closely the book by Wegeners wife. Both of these books are out of print.

Of the many things that make Wegener an interesting story, perhaps the most intriguing is that, although he was the author of a geological theory (continental drift), he was not a geologist. He was trained as an astronomer and pursued a career in atmospheric physics. When he proposed the theory of continental displacements (1912), he was thirty-one years old and an instructor of physics and astronomy at the University of Marburg, in southern Germany. He was not unknown. In 1906 he had set a world record (with his brother Kurt) for time aloft in a free balloon: fifty-two hours. Between 1906 and 1908 he had taken part in a highly publicized and extremely dangerous expedition to explore the coast of northeast Greenland. He was also knownto the much smaller circle of meteorologists and atmospheric physicists in Germanyas the author of a textbook, Thermodynamics of the Atmosphere (1911), and of a number of interesting scientific papers on atmospheric layering.

As important as Wegeners work on continental drift has turned out to be, it was largely a sideline to his principal career in atmospheric physics, geophysics, and paleoclimatology, and thus I have been at great pains to put Wegeners work on continental displacements in the larger context of his life and his other scientific work, and to put that life and work into the still larger context of the character of the earth and atmospheric sciences in his lifetime. This is a continental drift book only to the extent that Wegener was interested in that topic and later became famous for it. My treatment of his other scientific work is no less detailed, though I certainly have devoted more attention to the reception of his ideas on continental displacement, as they were much more controversial than his other work.

Readers interested in one aspect or another of Wegeners career will see that he often stopped pursuing a given line of investigation (sometimes for years on end), only to pick it up later. I have tried to provide guideposts to his rapidly shifting interests by characterizing different phases of his career as careers in different sciences, which is reflected in the titles of the chapters. Thus, the table of contents and the index should be sufficient guides for those interested in some aspect of Wegeners life but perhaps not all of it. My own feeling is that the parts do not make as much sense on their own as the ensemble of all his activities taken together. This is not an unusual standpoint for a biographer to take, but I do urge my readers to try to experience Wegeners life as he lived it, with all the interruptions, blind alleys, changes of mind, and renewed efforts this entailed.

In the most general sense, scientific biography exists to explain how the inner experience of certain individuals becomes the shared outer experience of the world that is science. The sciences are not about our inner, private experiences of the world, but only our shared, outer experiences of the world; only in this way can we compare the evidence and decide together what is true and what is not. This is a drastic restriction and a severe rule, but it is what allows the culture of evidence to exist and prevail against mere opinion.

In writing scientific biographies, we generally reconstruct the inner experience of scientists not from their published papers and books but from notebooks, letters, reminiscences of those who knew them, and other such material. Some scientists, such as Newton, Darwin, and Einstein, left mountains of such material behind, letters numbering in the tens of thousands. Others, like Michael Faraday, left extensive journals of their thoughts and speculations, parallel to their scientific notebooks. The more such material a scientist leaves behind, the better our chance of forming an accurate picture of how his or her ideas took shape and evolved. Of course, the sequence of scientific books and papers tells this story, but the story it tells is of the results, and not of the search. Since the seventeenth century, it has been the rule that scientists should report the results and not the history of their investigations: published science is someones version of a correct answer, with all the false starts, mistakes, and frustrations left out. Were it not so, the history of science as a scholarly undertaking would be nearly irrelevant, as the story behind the story would already be there.

Next page