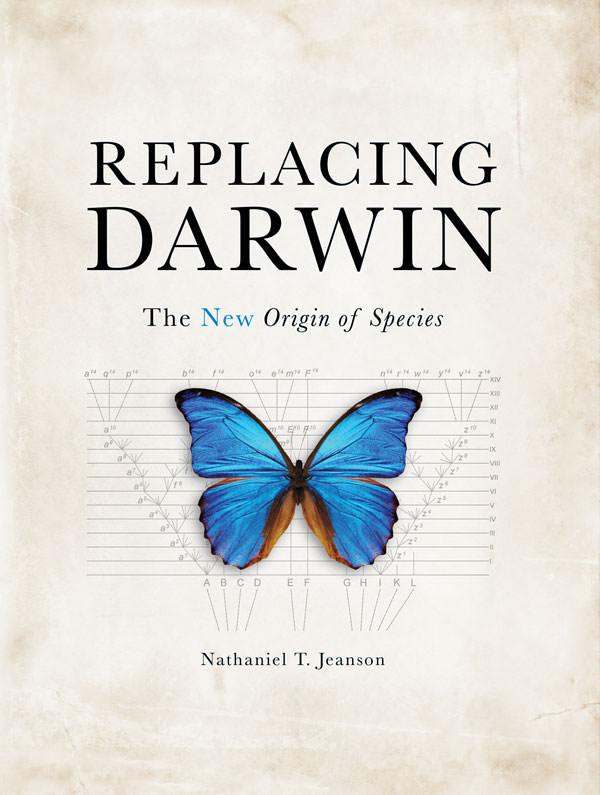

First printing: October 2017

Copyright 2017 by Nathaniel T. Jeanson. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations in articles and reviews. For information write:

Master Books, P.O. Box 726, Green Forest, AR 72638

Master Books is a division of the New Leaf Publishing Group, Inc.

ISBN: 978-1-68344-075-8

ISBN: 978-1-61458-634-0 (Digital)

Library of Con gress Number: 2017913476

Cover by Intelligent Designs Creative

Charis Hsu Illustrations - Copyright 2017

Unless otherwise noted, Scripture quotations are from the New King James Version (NKJV) of the Bible, copyright 1982 by Thomas Nelson. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Please consider requesting that a copy of this volume be purchased by your local library system.

Printed in the United States of America

Please visit our website for other great titles:

www.masterbooks.com

For information regarding author interviews,

please contact the publicity department at (870) 438-5288.

A portion of the proceeds from this book funds

continuing research on the origin of species.

To

Patrick, Jason, and Jos

And many more like them

Contents

Introduction

Why Now?

Chapter 1

Inevitable

T his book makes a bold claim that the events of the last 130 years have rewritten the history of life on this planet. On the surface, this statement might seem outrageous. A development this provocative would create at least as much upheaval as Darwins publication did.

Yet, upon deeper reflection, both revolutions become less surprising. In fact, in the wider context of the history of biology, you could argue that both paradigm shifts were inevitable.

To see how, an analogy is helpful. If we think of the origin of species* as a scientific jigsaw puzzle, each species is one piece of the bigger puzzle. Clues to their origins represent additional pieces. Paradigm shifts are major revisions in how the puzzle is put together.

This latter concept requires some explanation. For jigsaw puzzles that come in a box, paradigm shifts are rare. The box cover guides the progress, and the total number of pieces constrains the possible arrangements. Even if a puzzle is large, these two factors streamline and smooth the assembly process.

Unlike typical jigsaw puzzles, the puzzle of the origin of species does not come in a box. No cover exists. The final number of pieces are unknown. In fact, nearly all pieces must be actively sought. Consequently, with each new discovery, the potential for massive overhaul lurks in the background.

For example, consider the state of the puzzle prior to Darwins day. Just a century before Darwin published On the Origin of Species , the first pieces were discovered. In the late 1700s, Carolus Linnaeus entered the modern concept of species into our scientific vocabulary. Linnaeus and his contemporaries had very little data with which to work.

Nevertheless, despite this dearth, the available pieces suggested themselves into a plausible puzzle image. As a modern illustration of this old image, consider the polar bear species (Color Plate 1). It occupies a snowy environment along with its fellow Arctic residents, the Arctic fox (Color Plate 2) and Arctic hare (Color Plate 3). In all three species, white coats camouflage them against the stark Arctic environment.

If you move south to warmer climates, bears, foxes, and rabbits lose their white coats in favor of something more suitable. In the North American forests and mountain ranges, black bears lumber much more secretively than if their coats where white (Color Plate 4). In the grasslands and forests of Eurasia, red foxes dart more clandestinely than the Arctic fox would (Color Plate 5). In the blazing heat of the desert, jackrabbits dont need white coats; instead, they need to stay cool. Unlike arctic hares, jackrabbits possess large ears efficient thermoregulators (Color Plate 6). The challenges of each environment are matched by the unique features of each species.

This pattern is true globally. From the frigid ice floes of the Arctic to the tropical lagoons of the Great Barrier Reef; from the expansive Serengeti savanna to the dense Black Forest of Germany; from the airless slopes of the Himalayas to the soundless depths of the Pacific; from the deathly dry Sahara to the humid and lush jungles of the Amazon, species seem to have been made for the environments in which they reside.

The natural implications of these observations are clear. Going back to William Paley in 1802, scholars recognized that purpose implies design. Design implies a designer. With an analogy to the familiar realm of human design, Paley illustrated his reasoning. For example, if a watch were discovered lying on the ground, no one would explain its origin by the action of wind and rain over millions of years. Rather, they would observe the intricate fit of the parts to one another and conclude the obvious that a designer made the watch for a specific purpose. Similarly, the match between species and their environments suggested deliberate purpose as if, by the purposeful action of a Designer, species were designed for the environments in which they reside.

In technical terms, this view led to very specific conclusions in two arenas. Since species fit their locales so well, it would seem that they were made for their individual habitats that is, that they were created separate and distinct from other species. This implied that species do not become other species a view known as species fixity . Conversely, since species appear to have been made for their individual habitats, it would seem that they have always been in their current locations. Thus, in the arena of geography, the design argument implied the fixity of species locations.

In jigsaw puzzle terms, it was as if each species formed its own isolated puzzle. Environmental clues might decorate the outer edges of each species puzzle. But, rather than connect different species puzzles to one another, these clues seemed to separate the puzzles.

With few pieces in hand, this view was easy to maintain. The absence of obvious connecting pieces between puzzles produced a convincing set of isolated images. Nevertheless, due to the fact that many pieces were still waiting to be discovered, the potential for massive overhaul lingered.

By 1859, Darwin and his contemporaries had discovered many new pieces to these puzzles. Drawing on the growing knowledge in the fields of biogeography (i.e., the geographic distribution of species around the globe), anatomy, physiology, embryology, geology, and paleontology, Darwin began to see connections where prior investigators saw only empty space. Eventually, Darwin proposed that all species evolved from one or a few common ancestors a massive paradigm shift.

Because of the unusual nature of the puzzle of the origin of species, paradigm shifts are inevitable.

Like the 18th century, the scope of species diversity in Darwins day was a fraction of todays variety. In 1859, the scientific community had no knowledge of the majority of species we have now documented. With over 1.6 million

With Darwin barely 100 years removed from Linnaeus foundational work, this fact shouldnt be surprising.