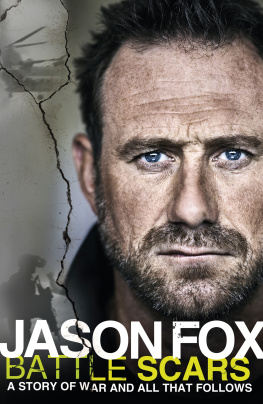

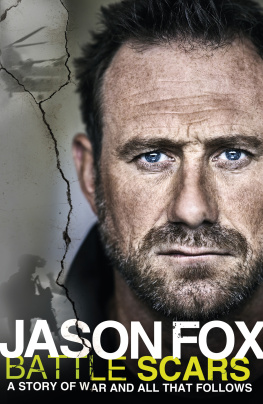

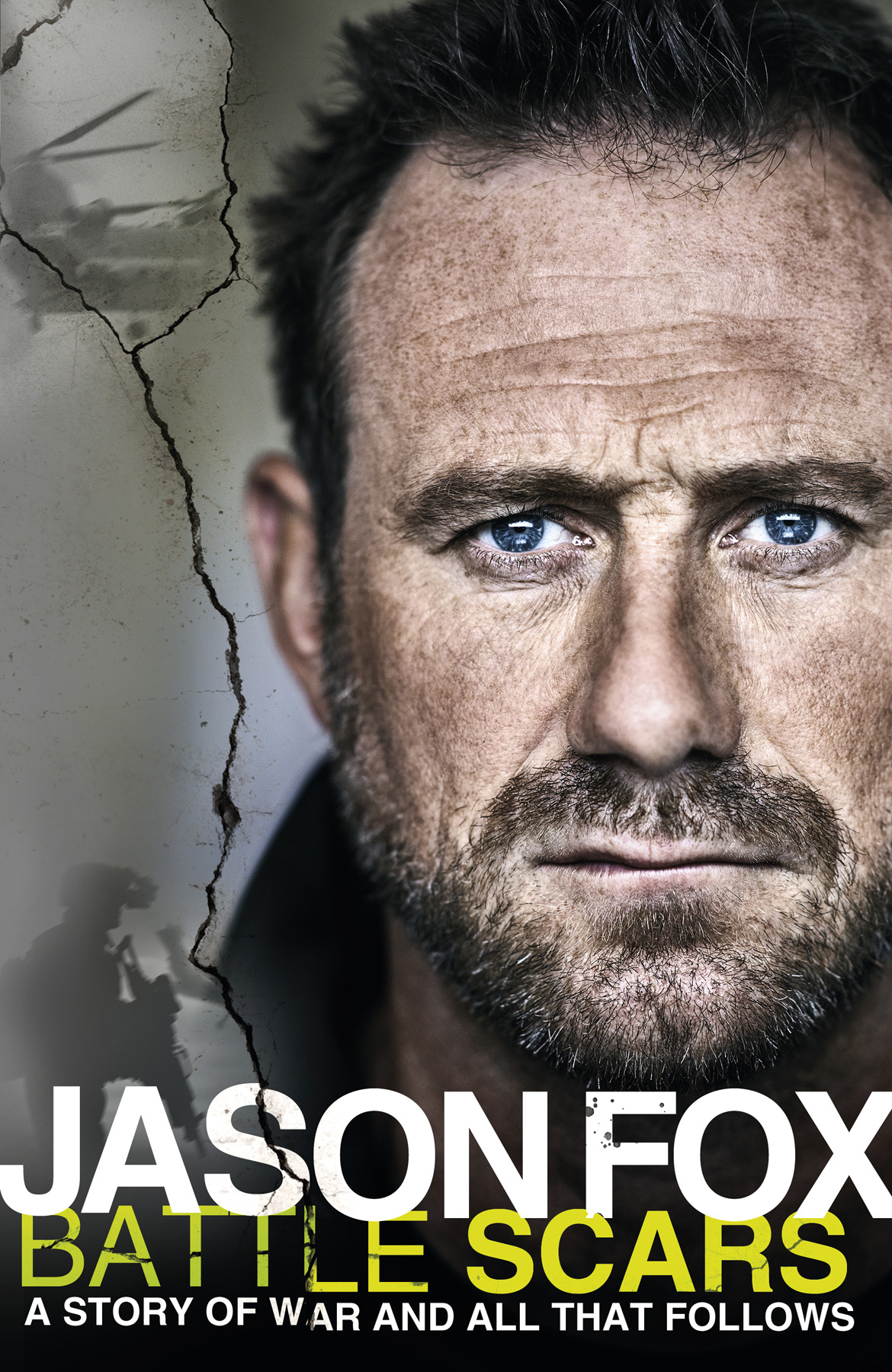

About the Book

Jason Fox served with the Special Forces for over a decade, thriving on the close bonds of The Brotherhood and the death or glory nature of their Missions.

Battle Scars tells the story of his career as an elite soldier, from the gunfights, rescue missions and heroic endeavours that defined his service, to a battle of a very different kind: confronting the psychological devastation of combat that forced him to leave the military, and the hard reality of what takes place in the mind of a man once a career of imagined invincibility has come to an end.

Unflinchingly honest, Battle Scars is a breathtaking account of extreme soldiering: a chronicle of operational bravery, and of superhuman courage on and off the battlefield.

Contents

BATTLE SCARS

A Story of War and All That Follows

Jason Fox

With Matt Allen

For the men and women engaged in their own personal conflicts with mental health issues.

This is my story.

The battles featured here occurred during the past decade in an unnamed warzone.

The names and locations featured in those operations have been redacted to protect the security of those involved and the practices of the British Special Forces. Some of the people involved in my struggle with mental health have also been disguised to protect their anonymity.

For my loved ones at home, the Killed In Action and survivors of war, everything else has been described as it happened

1

Is this my time?

Not here.

I want to go home.

I should be so lucky.

And were back there now, the place where it all started.

The sky erupted. Bullets with a blossom. Vivid puffs of phosphorescent green that sparked in the desert terrain below and sharpened into small dots, arcing towards our helicopter through a hazy, pea-soup blur. The trippy, spectral visuals were tracers, their surreal glow created by the night-vision goggles, the NVGs, strapped tightly across my face. Pop, pop, pop! Hundreds of them, more muzzle flashes in lime, more shooters, more rounds, speckling the ground a thousand feet down, suddenly zipping closer as I sat somewhere under the Chinooks whumping rotary blades. We had been spotted by a large group of enemy fighters, a couple of hundred at least, and their angry response was a rowdy launch of little lead wasps, each one approaching with an increasing velocity and brightness as they screamed by in their incandescent fury.

Anticipation grabbed at my chest. I was being wind-blasted from the air rushing through our windows, every glass pane on board smashed in to cool the oppressive desert heat outside air conditioning, British military-style. The heavy smell of aviation fuel had clung to my nostrils for a while, but as the helicopter descended ever more rapidly, an all-too-familiar stench took over. Sweet and pungent, the desert environment had a whiff all of its own: a weird blend of human and animal sewage, vegetation, dirt and body odour, the filthy essences mixed into an intensely rich and warm perfume. I could almost taste the habitation, the stink of mud buildings, the straw roofs, animal feed, dirty water and tangy manure. The rot and detritus cooked in the hot daylight, and even at night-time the smells never stopped wafting across the sand. During missions that involved a slow approach by land, there was an almost undetectable change in smell as we advanced, and my senses were often attacked subtly by aroma, kilometre by kilometre. But dropping rapidly out of the sky in a helicopter delivered a swift shock to the system and the odours blasted and tingled the hairs in my nostrils.

After several years of working in arid warzones, this reaction had become a trigger point, a warning I was moving into trouble. In the military we referred to those instinctive feedback loops as combat indicators, a sensual sign of looming conflict. On the ground, one of these triggers might have been something that didnt look quite right at the side of the road, a dug-up mound of earth maybe, or a hint of some recent enemy activity such as the not-so-subtle planting of an IED by an amateur. It was always a subconscious alarm bell, and my body and senses seemed to come alive with the realization Im in a helicopter, Im surrounded by teammates, and know that smell a fight was coming. Goosebumps prickled my skin; Kylie Minogue sang softly, sweetly, into my earphones, my iPod Shuffle delivering a surreal soundtrack to a night-op turned to hell when it could have easily thrown out something more befitting of the vibe, like the angry riffing of Iron Maiden or AC/DC. And then, a blast of pain hammered at my legs, an intense throbbing that seemed to begin in my kneecaps and wrenched at my thighs.

Oh no.

No.

No, no, no. Please not a hit.

I peered down nervously and squinted into the gloom, but I hadnt caught a bullet or shrapnel splinter. Instead, the stress of incoming fire had tweaked my bodys sympathetic nervous system, the fight-or-flight response, and Id instinctively grabbed at my knees, my fingers locking around the quad muscles in a white-knuckled grip as I painfully clutched at the flesh. Blowing away a sigh of relief, I pulled back and tried to reassure myself that everything was going to be OK. Im not going to cop a round not on this job. Weirdly though, there was no release from the throbbing sensation in my legs, even once Id grabbed at the barrel of my gun for comfort. I winced. It wasnt my knees Id been clutching in terror: Id been squeezing the soldier next to me, and hed been squeezing me. We looked at each other, realizing that a surreal moment of accidental tenderness had briefly unfolded, the pair of us kitted out in body armour, ammo, shock-and-awe weaponry. We had been touching each others thighs and giggled nervously like it was a weird first date. Two soldiers about to land in the middle of a gunfight, rounds pinging past us, our helicopters dropping into the heart of a village brimming with enemy fighters armed with AK-47 machine guns and rocket-propelled grenade launchers, both of us feeling embarrassed at a split second of unintentional intimacy. It seemed funny for a second or two unless you really thought about it.

A shout went up from the back of the chopper.

Three minutes!

The call was echoed down the line of waiting fighters, from ramp to cockpit, every voice reaffirming to the next man that it was Go Time. Three minutes during which nobody should be in any doubt that a proper scrap was about to kick off. Three minutes until we landed. Three minutes of helplessness, of not being in control of anything. With the Chinooks ramp slowly opening, I could assess our situation more clearly: Toyota Land Cruisers had pulled up underneath us, heavy machine guns mounted on the rear, the shooters on the back blowing the grainy green sky to ribbons. In response, our gunner popped off rounds, dragon-breath bursts looking to strike the targets below, but we were moving too quickly and it was almost impossible to hit anyone as we swooped down to 500 feet. I took a split second to check over my kit one final time: gun, ammo, radio; a frantic pat-down that always took place whenever we were about to execute a mission. I switched my iPod headphones for the standard-issue earpiece that linked every soldier working on the ground.

The buildings ahead sharpened in my night-vision goggles. The sturdy-looking huts, made from mud and straw, seemed to tumble over one another, unplanned and built seemingly without thought. Their edges were stacked along uneven lines and confusing alleys, and I could never understand how the rows stayed together. But the buildings robustness under fire made them architectural wonders to me; sometimes the walls were several feet thick and it was often hard work to blow in the perimeters if ever we had to breach a compound.