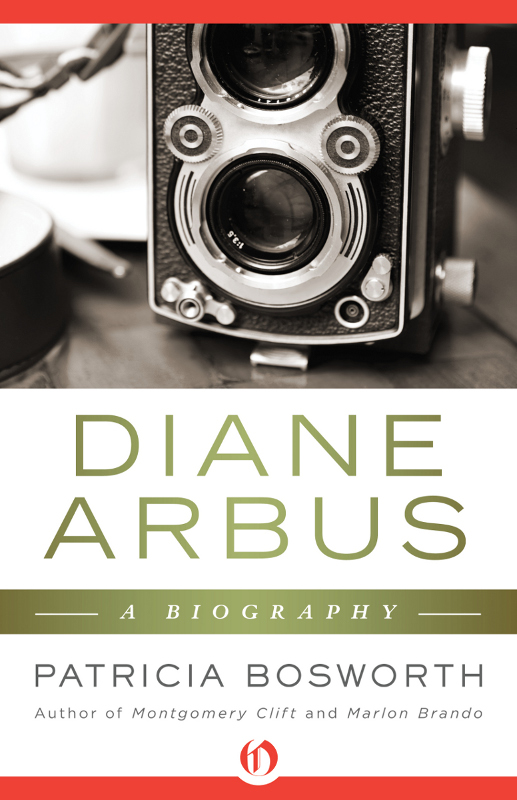

Diane Arbus

A Biography

Patricia Bosworth

For Mel

In memory of my late husband Mel Arrighi without whom this book could not have been written

Preface

DIANE ARBUS UNSETTLING PHOTOGRAPHS of freaks and eccentrics were already being heralded in the art world before she killed herself in 1971. Then, a year after her death, the Venice Biennale exhibited ten huge blowups of her human oddities (midgets, transvestites, nudists) that were the overwhelming sensation of the American Pavilion, as the New York Times art critic Hilton Kramer wrote. Soon afterward, a large retrospective of her work opened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and was both damned for its voyeurism and praised for its compassion; 250,000 people crowded in to see such haunting Arbus portraits as The Jewish Giant and The Man in Hair Curlers. Later the show toured the United States to acclaim and controversy and another retrospective was similarly received when it traveled throughout Western Europe, Australia, Japan, and New Zealand. Arbus gained an international reputation. Subsequently a book of eighty of her photographs was published by Aperture. Its overriding themessexual role-playing and peoples irrevocable isolation from each otherseemed to express the rebelliousness, alienation, and disillusionment that had surfaced in the sixties and flowed into the seventies. The book has since sold more than 100,000 copies.

It is possible that Arbus would not have received such concentrated attention had she lived, although it is generally acknowledged that her rough uneasy style (which combined snapshot technique with the conventions of heroic portraiture) did in any case have a seminal influence. She drastically altered our sense of what is permissible in photography; she extended the range of what can be called acceptable subject matter. And she deliberately explored the visual ambiguity of people on the fringe and at the center of society.

Back in the fifties her images were strictly one-dimensional. I met her then. When I was eighteen I modeled for her. In those days Diane Arbus was a fashion photographer in partnership with her husband Allan. They worked constantly for Glamour and Vogue and various advertising agencies. They hired me to pose for a Greyhound bus ad. It was my first big booking.

I remember thinking, on that hot summer morning so long ago, that my carefully applied pancake makeup might streak my neck. I was terrified that even in my falsies, waist-cincher, crinoline petticoats, and shirtwaist dressthe standard uniform for a John Robert Powers modelI would be told that theyd made a mistake, that I was wrong for the job. However, the moment I entered the Arbus studio on East 72nd Streeta huge, cool echoing place decorated with an enormous green treea barefoot Diane ran over to me with outstretched arms. Good! she declared. You dont look like a model. And then in a conspiratorial whisper: Thats why we hired you.

The rest of the day passed swiftly. We went on location (another first for me), driving to Ardsley Acres, a small town less than fifteen miles from Manhattan, and stopping at a dead-end road where weeping willows surrounded a pond. Until it got dark I posed, together with a male model who played my date, in front of an empty Greyhound bus, while between takes Diane fussed with my hair and murmured encouragement. It was Allan who took all the pictures (I learned later that he and Diane alternated shooting). She addressed him as boy and he called her girl, and they had an assistant, Tod Yamashiro, a young Japanese photographer from Chicago, who kept loading their cameras. The three of them seemed to have a warm, joking relationship, and by the end of the afternoon I was laughing and joking, too. Driving back to the city, I felt exhilarated as Diane plied me with gentle questions and then listened to my answers with such intensity I believed I had never spoken so articulately or been so well understood. (Later I discovered that Diane consistently had this effect on people. When you were talking with her, she made you feel as if you were the most important person in the world, says her old friend Stewart Stern.)

I worked for Diane twice after that, I think, and then when I became a journalist I continued to see her occasionally. Wed run into each other on the street and have long, rambling conversations. Once we sat in a coffee house while she told me shed left fashion and was doing her own thing, photographing strangers on Coney Island. Another time, riding together on the up escalator in a department store, she informed me that shed won a Guggenheim, which would enable her to travel around the country photographing events and celebrations. She had just photographed a beauty contest at a nudist camp in Pennsylvania, she said. I subsequently recognized one of the pictures from that take when I saw it along with other of her portraitsa woman with a cigar, kids dressed as grownups, grownups dressed as kidsat the Museum of Modern Art. They were part of a 1967 show called New Documents, a crucial exhibit because it marked the end of traditional documentary photography and introduced a new approach to picture making, a self-conscious collaborative one in which both subject and photographer reveal themselves to the camera and to each other. The result is a directness that pulls the viewer smack into the life of the image.

By 1978 Diane Arbus stature as a preeminent photographer was unquestionedshe was linked to Walker Evans and Robert Frank in importanceand yet nothing had been written about her life, although it was obvious that behind her pictures lay a strange and powerful person.

She once said, A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you the less you know. I set out to probe this secretto explore her mysteryto illuminate if I could the sources of her vision. However, when I met with Doon Arbus, Dianes oldest daughter and the executrix of the Arbus estate, she told me she could not contribute to any biography that touched on her mothers lifethat the work speaks for itself. Dianes former husband Allan decided not to contribute, as did their younger daughter Amy and certain close friends including the late Marvin Israel.

I did find a great many people who were more than willing to help me piece together Dianes worldsthe mercantile world of Russeks Fifth Avenue (her familys department store), the glittering world of fashion, and the dark world of freaks and eccentrics she was so irrevocably drawn to.

From the very beginning Diane Arbus brother, the distinguished poet Howard Nemerov, gave me his complete cooperation and support. I visited him at his home in St. Louis and we corresponded regularly. I have also gathered copious reminiscences from the rest of Dianes family: her mother Gertrude Nemerov, her sister, Rene Nemerov Sparkia, her brother-in-law Roy, her sister-in-law Peggy Nemerov. I interviewed cousins, aunts, uncles, and many of the people who worked at Russeks; I talked to Dianes school friends from Fieldston, Phyllis Carton (now Contini) and Eda LeShan, as well as to teachers like Elbert Lenrow and Victor DAmico who first recognized her special visual talent.

Some of the most significant conversations I had were with the women who were close to Diane Arbus, like her god daughter May Eliot and her photography teacher Lisette Model. I owe a special debt to Charlie Reynolds, a photographer who shared Dianes love of circuses and magic, and to Neil Selkirk, who has printed all of Dianes work since her death. With regard to her work, although the Arbus estate did not give me permission to reproduce any Diane Arbus photographs, I was able to document in my book the evolution of many of her images, often by speaking to those subjects still alive. My gratitude to them for their time and recollections. And thanks to those collectors who have kept some of Arbus earliest un-published attempts with a camera and allowed me to study them. Special thanks to gallery owner Lee Witkin who directed me to much source material and who also lent me a rare Arbus portfolio to pore over.

Next page