Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Dedicated to the memory of my grandparents Aubrey Gladwin and Lalage Bagley Gladwin, and the millions like them who perished in the Spanish flu pandemic of 191819.

It was the beginning of the rout of civilisation, of the massacre of mankind.

H. G. Wells, War of the Worlds

The Captain looked suddenly tired. Sometimes I think, Mr. Benson, that the very air is poisoned with the damned influenza. For four years now millions of rotting corpses have covered a good part of Europe from the Channel to Arabia. We cant escape it even when were 2,000 miles out to sea. It seems to come as it did on our last trip, like a dark and invisible fog.

Herbert Faulkner West, HMS Cephalonia: A Story of the North Atlantic in 1918

Fly this plague-stricken spot! The hot, foul air

Is rank with pestilence the crowded marts

And public ways, once populous with life,

Are still and noisome as a churchyard vault;

Aghast and shuddering, Nature holds her breath

In abject fear, and feels at her strong heart

The deadly fangs of death.

Susanna Moodie, Our Journey up the Country

A S THE SUN sank over a windswept Yorkshire churchyard in September 2008, a battered lead-lined coffin was reburied hours after being opened for the first time in eighty-nine years. The familiar words of the burial service resounded through the twilight as samples of human remains were frozen in liquid nitrogen and transported to a laboratory with the aim of saving millions of lives. Medical researchers had exhumed the body of Sir Mark Sykes (18791919) in order to identify the devastating Spanish flu virus which killed 100 million people in the last year of the First World War. Sir Mark, a British diplomat, had succumbed to Spanish flu during the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, dying in his hotel near the Tuileries Gardens. Like many victims of Spanish flu, Sir Mark had been fit and healthy, a man in his prime at just thirty-nine years old.

Sir Marks remains had been sealed in a lead-lined coffin, befitting his status as a member of the nobility, and transported to Sledmere House, the Sykes family seat in east Yorkshire. Sir Mark was buried in the graveyard of St Marys church, which adjoined the house. If his body had not been hermetically sealed by a thick layer of lead, his life might have passed quietly into history. But an accident of chemistry meant that the lead dramatically slowed the decay of Sir Marks soft tissue, giving scientists investigating the H5N1 bird flu virus a unique opportunity to study the behaviour of its predecessor. One theory of the cause of the 191819 epidemic was that it originated with an avian virus, H1N1, which is similar to H5N1. Researchers believed Sir Marks remains might hold valuable information about how the influenza virus leapt the species barrier from animals to humans.

In 2011, there were only five useful samples of the H1N1 virus around the world and none from a well-preserved body in a lead-lined coffin. H1N1 had already been sequenced by scientists using frozen remains found in Alaska, but many questions remained about just how the virus killed its victims and the way it had mutated by 1919, when it killed Sir Mark Sykes.

Professor John Oxford, the eminent virologist who led the team investigating Sir Marks remains, told reporters that the baronet died very late in the epidemic, when the virus had almost burnt itself out. We want to get a grip on how the virus worked both when it was at its most virulent and when it was coming to the end of its life. The samples we have taken from Sir Mark have the potential to help us answer some very important questions.

After a two-year process of gaining permission from the Diocese of York to carry out the exhumation, involving a special hearing presided over by a High Court judge, Professor Oxfords team, wearing full bio-hazard kit and accompanied by medical experts, clergy, environmental health officers and Sir Mark Sykes descendants, finally exhumed his grave. After a short prayer, the gravestone was removed and the coffin uncovered inside a sealed tent before researchers wearing protective suits and breathing apparatus opened the casket. After so many months of preparation, it was a tense and exciting moment. But the investigation seemed doomed to failure. A crack was discovered in the top of the lead lining, meaning that the chances of finding a pristine sample of the virus were remote. The coffin had split because of the weight of soil over it, and the cadaver was badly decomposed. Nonetheless, the team were able to extract samples of lung and brain tissue through the split, with the coffin remaining in situ in the grave during this process to avoid disturbing the body any further. Although the condition of the cadaver was disappointing, a study of the tissue samples taken from the remains eventually revealed valuable genetic imprints of H1N1 and its condition when Sir Mark died.

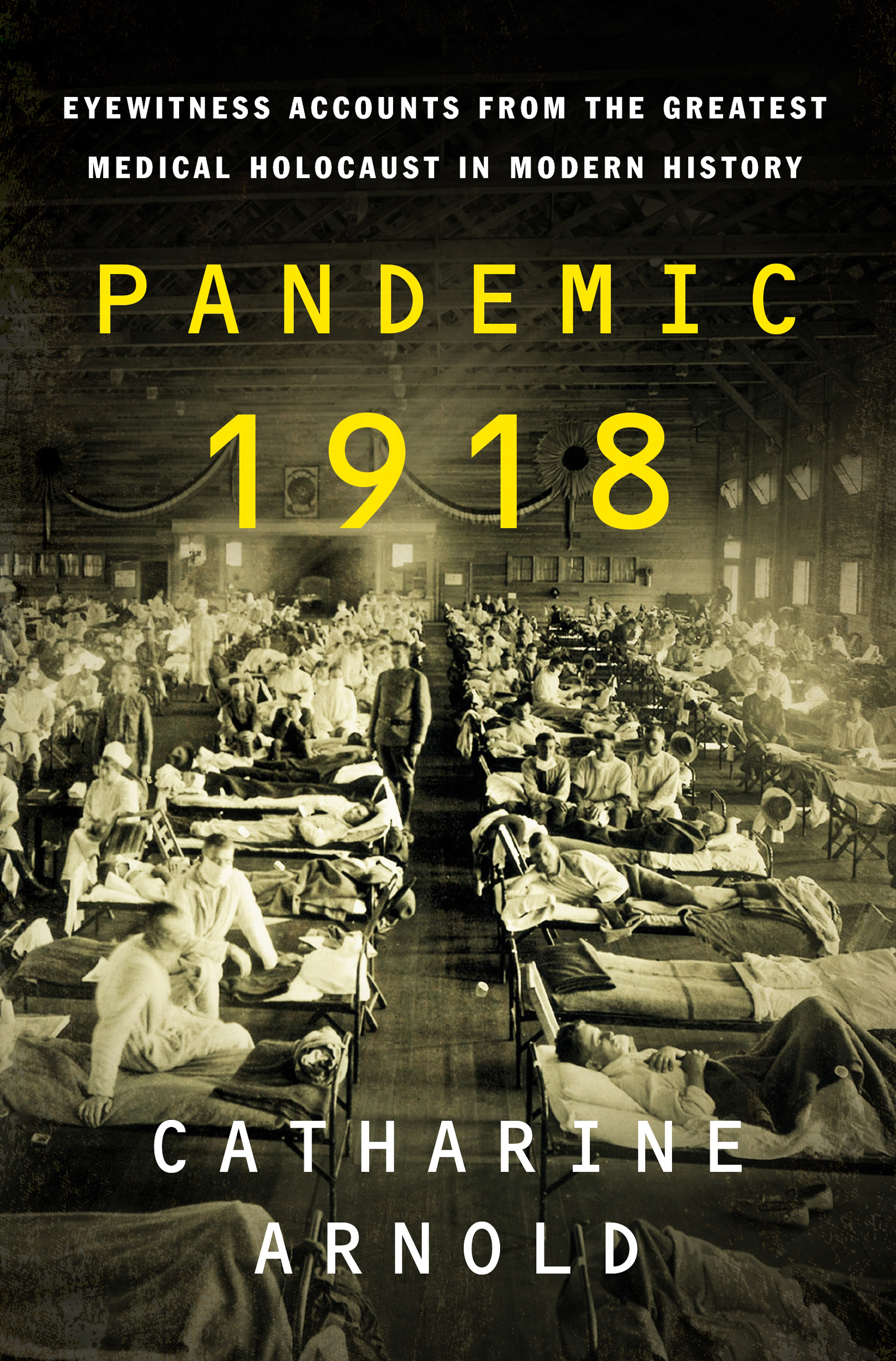

The exhumation of Sir Mark Sykes body represented just one attempt to find an explanation for the deadly disease that had devastated the globe during the last year of the Great War. In three successive waves, from spring 1918 to summer 1919, the phenomenon that became known as Spanish flu killed an estimated 100 million people worldwide. The disease was not classified as Spanish flu, or the more fanciful soubriquet Spanish Lady, immediately. The shape-shifting creature that was Spanish flu was a slippery beast, difficult to define beyond the common characteristics of acute breathing difficulties, haemorrhaging and fever. As it progressed, many doctors and civilians would wonder whether this apocalyptic disease was actually influenza at all.

In terms of national identity, there was nothing inherently Spanish about Spanish flu. At first, in the early months of 1918, the majority of doctors believed they were dealing with nothing more serious than a particularly aggressive outbreak of common or garden influenza. But as the epidemic continued, and King Alfonso XIII of Spain fell victim along with many of his subjects, this virulent strain of influenza was discussed freely in the Spanish press. Debate of this nature was possible as Spain was a neutral country during the First World War. Elsewhere, in Britain and the United States, censorship made such speculation impossible beyond the pages of medical journals such as The Lancet and the British Medical Journal. Under DORA, or the Defence of the Realm Act, newspapers were not permitted to carry stories that might spread fear or dismay. As the term Spanish flu entered the language in June 1918, The Times of London took the opportunity to ridicule the disease as little more than a passing fad. By the autumn of 1918, when the deadly second wave of Spanish flu was hitting populations worldwide, the implications of the disease proved impossible to ignore. The United States recorded 550,000 deaths, five times its total military fatalities in the war, while European deaths totalled over two million. In England and Wales an estimated 200,000, 4.9 per 1,000 of the total population, perished from influenza and its complications, particularly pneumonia.