THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Random House Childrens Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

For picture credits, please see .

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN9781101931462 (trade) ISBN9781101931479 (lib. bdg.) ebook ISBN9781101931486

Random House Childrens Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

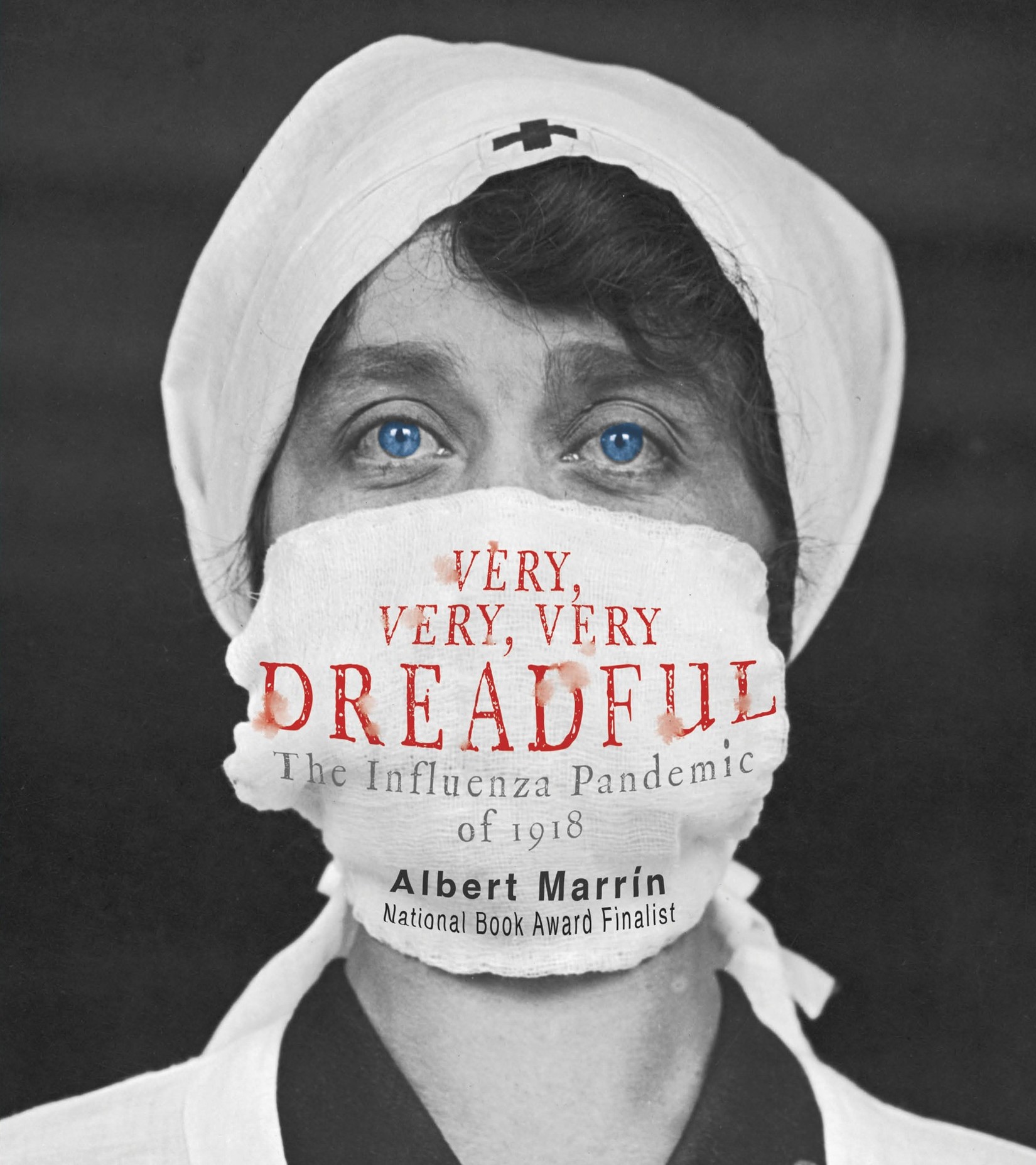

This may serve to describe the dreadful condition of that day, though it is impossible to say anything that is able to give a true idea of it to those who did not see it, other than this, that it was indeed very, very, very dreadful, and no such tongue can express.

If you are in the business of infectious disease epidemics, you cant ignore the 1918 fluits the great-granddaddy of them all.

Dr. Donald Burke, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 2004

Monday, March 11, 1918. Fort Riley, north-central Kansas. On a vast windswept plain covering more than 20,000 acres, scores of barracks, staff buildings, warehouses, repair shops, stables, and tent cities dotted the grounds. Rumor had it that ghosts roamed the parade ground on nights of the full moon, when coyotes howled. Fort Riley was home to the Seventh Cavalry, the unit that, forty-two years earlier, Colonel George Armstrong Custer had led to fight the Sioux and Cheyenne during the Indian wars.

That late-winter day in 1918 dawned cold and gray. Army recruits shivered, for, one wrote his folks, barracks and tents were overcrowded and inadequately heated, and it was impossible to supply the men with sufficient warm clothing. To make matters worse, sand blown by gale-force winds stung bare skin and got into eyes and mouths, crunching between teeth. It had, some said, the faint smell of manure. Though Fort Riley had scores of motor vehicles, the U.S. army still used thousands of horses and mules to haul supplies. The animals left manure all over, which cleanup squads raked into piles, waist-high, for burning every few weeks. Two days earlier, work details had burned several hundred tons of the stuff with fuel oil. The fires gave off a foul yellowish haze, the wind scattering the powdery ashes into the sleeping quarters and mess halls.

Fort Riley, Kansas. (c. 19181919)

Recruits had swarmed into Fort Riley because their government sent them there. A savage war had been raging for nearly four years, since July 1914. Then called the Great War or the World War, today we know it as World War I or the First World War. Mainly, it was a struggle for power in Europe and for overseas colonies, raw materials, and markets. Two groups of nations fought. On one side stood the Central Powers, led by Germany and including Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire, ruled by the Turks. Opposing them were the Allies, primarily the British Empire, France, Russia, and Italy. Though waged chiefly in Western Europe, the war spilled into nearly every corner of the globe.

Neutral at first, American public opinion gradually tilted in favor of the Allies. With the worlds largest economy, the United States needed to trade its manufactured goods to prosper. But when Britains Royal Navy blockaded Germanys seaports, cutting off overseas supplies of food and raw materials, Germany retaliated, unleashing its submarines to keep vital supplies from reaching the Allies. After German U-boats (undersea boats, or submarines) torpedoed American cargo ships, Congress declared war in April 1917.

Even though the United States was the worlds industrial leader, its 378,000-strong army was tiny compared to the millions of men fielded by the European powers. A latecomer to the war, the United States was embarrassingly short of modern weapons, many of which it had to buy or borrow from the Allies. Americas chief advantage was its manpower. Within days of the declaration of war, the nation set about creating an army of more than 4.7 million men, the largest in its history until then. Basic infantry training would take place in thirty-two camps across the country, and in dozens of facilities where specialized skills such as artillery, military engineering, and flying airplanes would be taught. Fort Rileys training area, called Camp Funston, held 56,000 recruits, making it the largest camp in the country.

Among the recruits was Private Albert Gitchell, a mess cook. Before daybreak on March 11, 1918, Gitchell awoke feeling achy, his throat raw, as if scoured with hot sandpaper. Too sick to prepare breakfast for his company, he dragged himself to Hospital Building 91. The orderly on duty took the privates temperature and promptly put him to bed with a bad cold. But then a strange thing happened. Moments after Gitchells head hit the pillow, Corporal Lee W. Drake appeared with the same complaint. Others quickly followed. By noon, 107 men had been admitted to the hospital with bad colds. And that was just the beginning: within two weeks, a total of 1,127 men had been stricken. Upon closer examination, doctors decided they had an influenza outbreaka local flare-up of an infectious diseaseon their hands.

Influenza! Influenza! Just let the word slide off your tongue; it has such a mellow sound. Yet its history is anything but mellow. The name comes from the Italian influenza coeli, meaning influence of the heavens, for Italian scientists in the 1600s thought meteors, comets, and the position of the planets shaped events on Earth. A century later, English speakers borrowed the Italian word; flu is simply a shortened form of influenza. The French called it la grippe, from gripper, to grasp or hook, because the infection grabs hold of its victims.

Influenza outbreaks were usually an annual winter event in the Northern Hemisphere. Always a nuisance, flu sickened many but was gone after a few days of misery. Before 1918, most people, including physicians, were blas about flu, accepting it as an expected part of life, to be endured, along with taxes and toothaches. Influenza, the New York Times reported in 1901, has apparently become domesticated with us.

The diseases early symptoms resemble those of the common cold, only more severe: fever, cough, runny nose, muscle aches, fatigue. Harvey Cushing, a brilliant brain surgeon, caught