To the memory of my father

BASIL MONTAGUE RICE

(19091982)

and

my great-grandmother

KATHERINE MEIKLEJOHN HERCOCK

ne Reid

(18431918)

last victim of the 1918 flu in Taumarunui

and to all the victims and survivors of

New Zealands worst disease disaster

CONTENTS

This book had its origins in an after-dinner conversation with my father in 1977. I had been reading an exciting little book by Edward Shorter, The Making of the Modern Family (1975) and, as a new parent, had become interested in the history of households and families in the past. We were talking about his childhood in Taumarunui, which was then a raw new railway and timber town in the middle of the North Island, and I asked him to name the most vivid experience of his childhood. Without a moments hesitation he replied, Why, the Black Flu, of course. This rang no bells for me, so I asked, When was that? His reply, as I recall, went something like this:

That was the big flu epidemic at the end of the First World War. I thought everyone had heard about the Black Flu. You wouldnt forget it if youd lived through it. People collapsed and died like flies, even big strong men in the prime of life. In fact it seemed to affect them worse than the weedy types. It came on a ship called the Niagara. Massey and Ward were coming back from some war conference in London, and they didnt bother to quarantine the ship. It went through the country like wildfire. Thousands died in that flu, especially the Maoris. They seemed to get it worse than the rest of us. But I dont remember ever seeing an official death toll. Perhaps they were too afraid to publish the figures.

He then told me how Taumarunui had come to a complete standstill for what seemed like several weeks, with all the shops and pubs shut and nearly every adult in the town laid low with the flu. His family was one of the lucky ones that seemed to be immune. My grandparents spent all day every day visiting their sick neighbours and feeding the convalescents. At first my father went with them. His job was to light the fires each morning in the coal ranges which then heated the water and warmed the houses. He was very proud of his system. Having set the paper and kindling in three houses, he would return to light them, and by the time the third one was lit the first one would be ready for more wood. Then he would repeat the round to add coal, before moving on to the next three houses. Nobody needed to lock their doors at night in those days.

As well as lighting the fires my father also had to look into the bedrooms to see if anyone had died in the night. In my ignorance I asked, How could you tell? Theyd just look as if they were asleep. I will never forget the shock of his reply:

Oh, you could tell all right. In that flu, when they died, the bodies turned black. Thats why your Nanna always called it the Black Flu. In one house I looked into a bedroom and there was the wife, still fast asleep, and her husband dead and black beside her. It was a terrible time. I had to turn it in after that, I just couldnt carry on.

He was only nine years old in 1918.

My mother had been spared such sights. She was a bank managers daughter in Levin, aged ten. The schools were all closed and it was the longest summer holiday she ever had. She remembered the celebrations at the end of the Great War, and showed me the medal her sister had won at the Levin Armistice Sports. But then the epidemic took hold and they were not allowed outside the property until it was over. My mother remembered the strong smell of disinfectant in the bank, and her mother worrying in case her father caught the flu germ from counting banknotes. She also heard her parents whispering about people they knew in the town who had died. But none of their close friends caught it or died.

As soon as possible I went to the Canterbury Public Library and asked to look up the old newspaper files from 1918. Sure enough, November 1918 was full of news about influenza, taking over from the bold headlines announcing the Armistice and the end of the Great War. As I turned the pages the death notices of epidemic victims began to outstrip the war casualties in the Roll of Honour columns. Full-page official notices appealed for volunteers to report to their local block committee, women with nursing experience were asked to report for duty at their nearest temporary influenza hospital, and detailed instructions were given to those nursing flu patients at home: Patient to be isolated in bright, well-ventilated room. Be sure windows open fully. No one except the nurse or attendant to enter room. There were notices from the Health Department declaring the closure of all dance halls, theatres, billiard saloons and places of entertainment until further notice. Other official notices announced the location of inhalation chambers where people could breathe a vapour designed to kill the flu bugs. In Christchurch these appeared to be mostly tramcars stationed at various termini around the city.

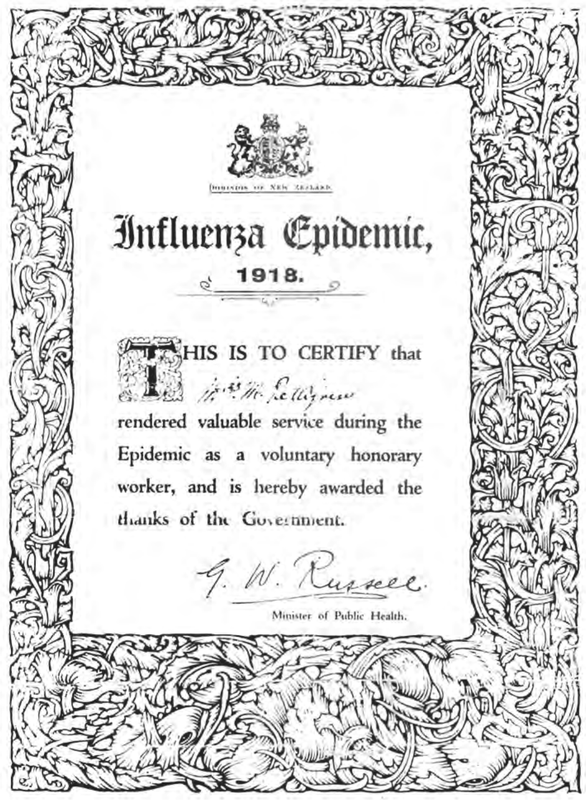

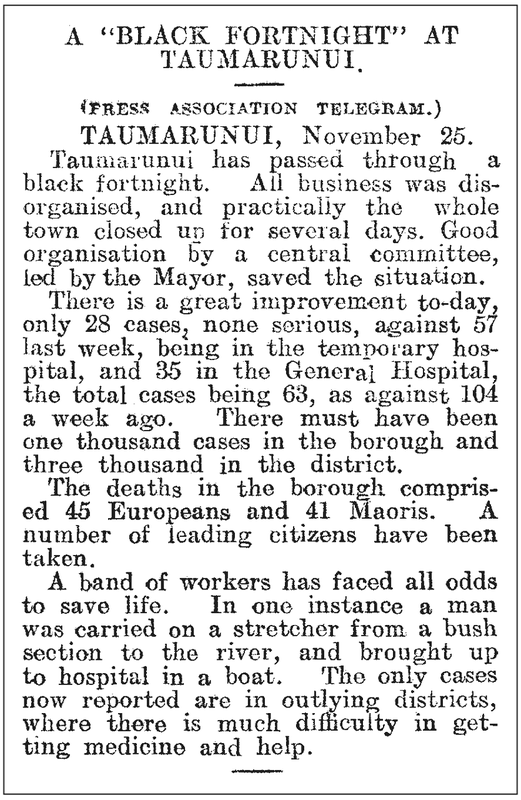

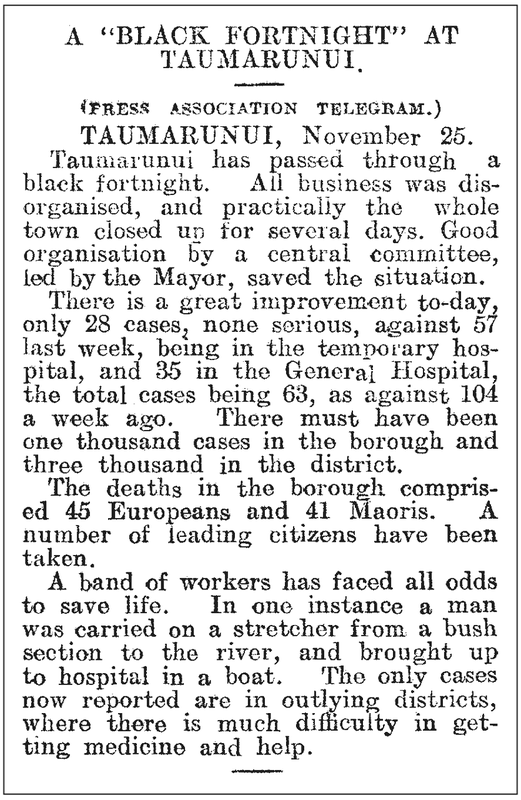

Then I found a column headed Black Fortnight in Taumarunui that confirmed many of my fathers recollections. It seemed to have been one of the worst-affected North Island towns, with 1,000 flu cases in the borough and 3,000 in the surrounding district. A small band of volunteers organised by the mayor had braved all odds to save lives. Presumably that small band included my grandparents. Yet over fifty Europeans had died, and many more Maori deaths were feared.

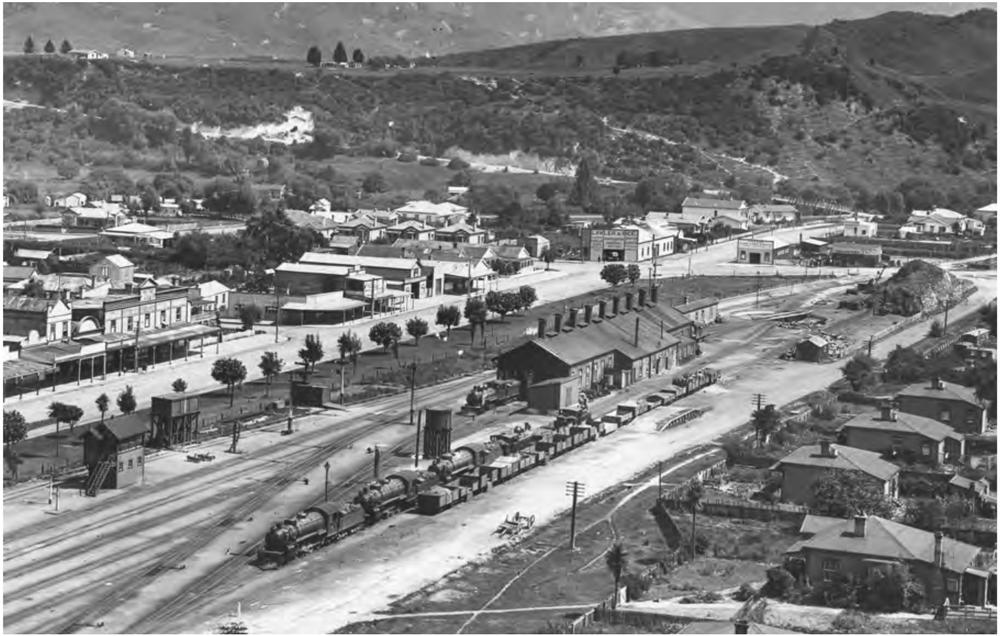

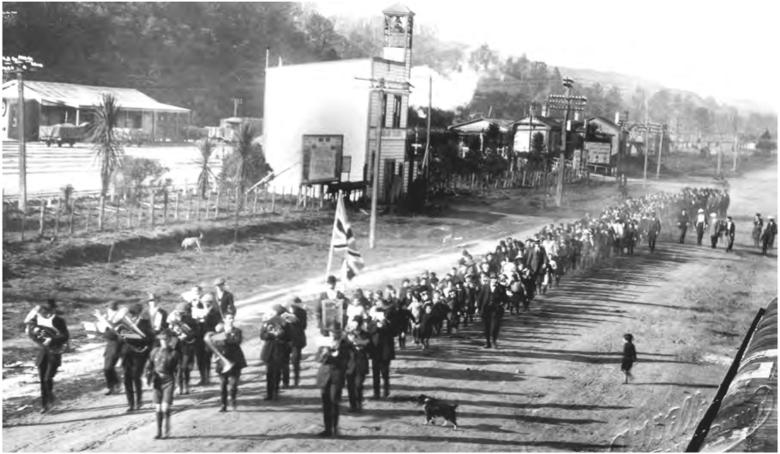

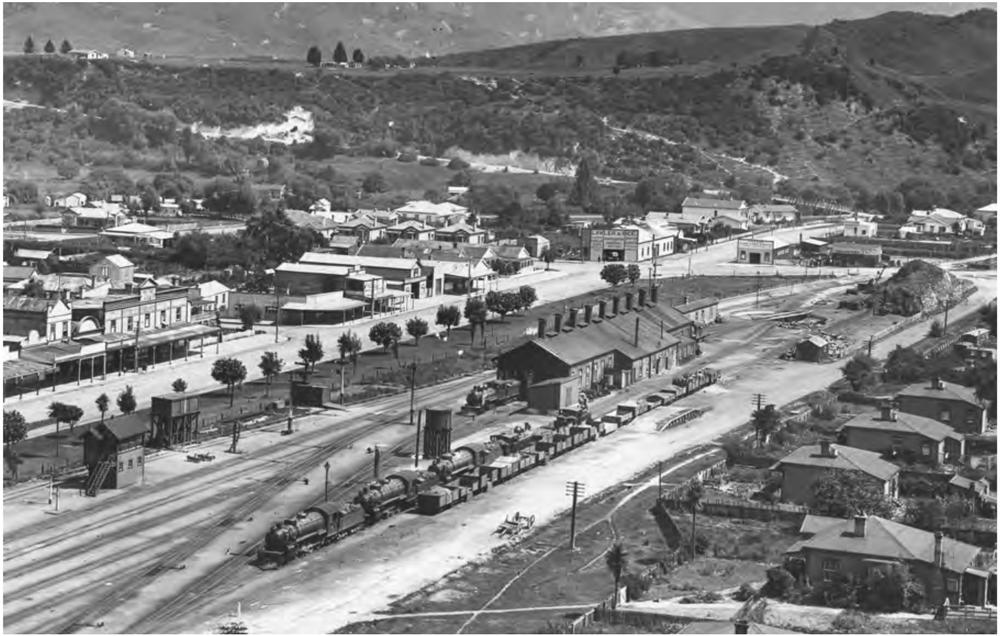

Taumarunui, 1912: view northwest across the railway engine shed. Lawler and Rice, general engineers, on Hakiaha Street. Maori pa on plateau in background.

Authors collection

There were similar stories from many other towns, of volunteers setting up temporary hospitals and soup kitchens, of relief parties motoring out to visit the nearest Maori pa and finding dozens of people dead or dying, of tragic deaths leaving a whole family orphaned, or soldiers returning from the war to find a mother or brother dead from the flu. I was curious to know just how many people had died, but the newspapers had very few figures. It was as if there had been an official ban on such depressing details. Burials for the four main centres, however, indicated hundreds if not thousands of deaths in the space of only a few weeks. Auckland had the biggest death toll, just over a thousand, and there were so many bodies that special trains had to be arranged to take the coffins to Waikumete Cemetery.

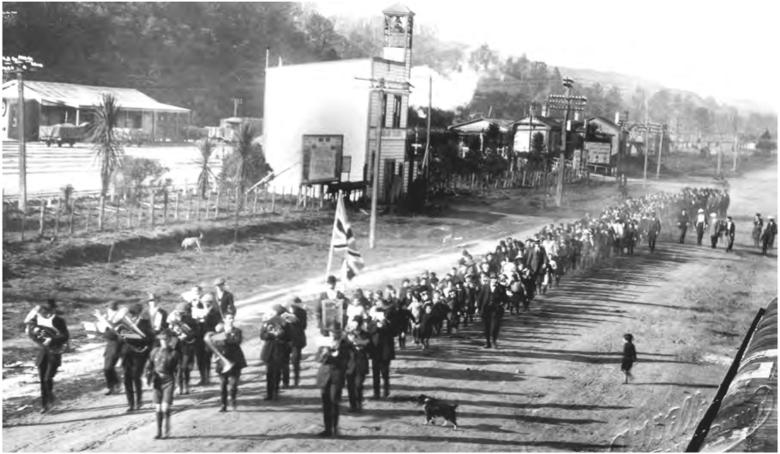

Taumarunui, 12 November 1918: Armistice parade on Hakiaha Street, childrens section. Fire station and railway station in background.

Photo by A. Willis, courtesy of Ron Cooke, Taumarunui

How had I not heard about such a major event in New Zealand history? I could not recall hearing about it at school, and though I had taken a course in New Zealand history as part of my degree it had been mostly concerned with politics and made no mention of a great epidemic. All my subsequent research and teaching had been in European history.

A brief report from The Press, Christchurch. North Island newspapers gave more detailed reports on the flu in Taumarunui.

A quick check of standard textbooks turned up only a terse two-line statement in Keith Sinclairs