We know much about how personal behaviours, choices and genes influence individual health. This enterprising, well-written and timely book asks a bigger question: What cultural, political, commercial and socioeconomic influences explain the trends over several centuries in New Zealands population health and life expectancy? The authors exploration of major differences in health trends between Mori and Europeans (Pkeh) provides further valuable insights and just when the need for sustainable and healthier ways of living is pressing on us all.

Professor Emeritus Tony McMichael, Australian National University

The history of life and death in New Zealand is of wide interest, both because New Zealand held the record for life expectancy over a long period and because of the experience of the indigenous population. Written in a lively style by internationally renowned scholars, this book provides a convincing synthesis of life expectancy from pre-European times to the present and it will be welcomed by readers around the world.

Professor Dr Johan P. Mackenbach, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam

THE HEALTHY COUNTRY?

A History of Life & Death in New Zealand

Alistair Woodward & Tony Blakely

LIST OF FIGURES

LIST OF TABLES

PREFACE

New Zealand offers unexpected insights into human longevity and, especially, helps to explain the astounding mortality reductions that have occurred in most countries, most of the time, in the last 150 years. For New Zealanders this book is about who we were, who we are now and how we might live in the future. Further afield, we hope our story will attract readers who are curious about the links between location, history, social circumstances, physical environments and health. Stephen Kunitz notes that it is particular realities as much as generalities that matter when trying to decipher trends in longevity; and as a small island nation remote from the mainstream of biological history and human settlement, New Zealand certainly does have its own particularities. We are writing also for students in public health and epidemiology, be they formally enrolled students or (like us) just wanting to learn more. Dont mistake this for a comprehensive textbook. It roams the borders and neglects disciplinary heartlands, but we hope our book adds to the standard treatments with detail, colour, connections and, perhaps, surprise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Sam Elworthy of Auckland University Press prompted the idea for this book over coffee some years ago, and then shepherded us through the process.

The University of Auckland and the University of Otago have generously granted sabbatical time for us to research and write the majority of this book.

The Health Research Council of New Zealand and the Ministry of Health funded the New Zealand Census-Mortality Study and the CancerTrends Study that together contributed many of the data we present in .

We have been fortunate to receive enthusiastic and wise comment on drafts of this book from many of our colleagues and friends: Robert Beaglehole, Ruth Bonita, Linda Bryder, Hera Cook, Caroline Daley, Tahu Kukutai, Richard McKenzie, Tony McMichael, Alison OConnell, Papaarangi Reid, Anthony Rodgers, Diana Sarfati, Richard Taylor, Martin Tobias and Nick Wilson. We also appreciate the comments of two anonymous Auckland University Press reviewers.

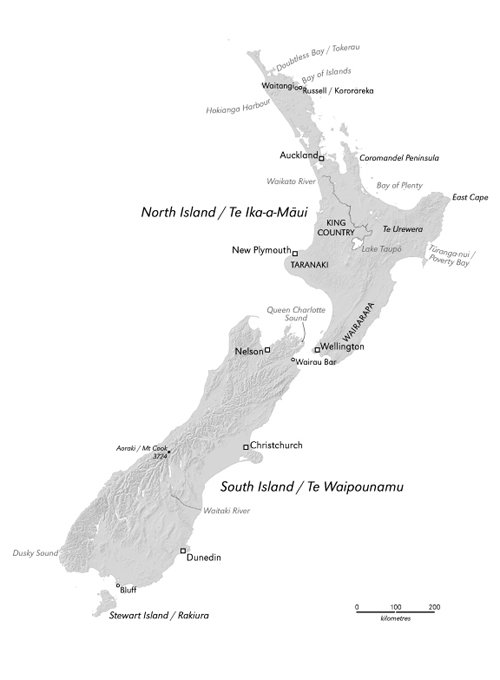

We thank Kate Sloane, who helped with the preparation of the figures and numerous other editing tasks; Ginny Sullivan, for copyediting and indexing; and Igor Drecki for the redrawn map of New Zealand.

Introduction

Was born, is dead.

Let this be said

on stone over my head

or graven on urn

when it is my turn.

Denis Glover, Epitaph

We live in an age of speed and transformation. Since 1965, computer-processing power has doubled roughly every two years. If you were born before 1970, the worlds population has doubled in your lifetime. The press of human activity has overwhelmed the natural environment. If current trends continue, carbon dioxide (CO) levels in the atmosphere will double by the end of the century, and the acidity of the oceans will increase by 150 per cent. These changes are remarkable. But for a species to double actually soon triple its life expectancy over a period of less than ten generations is, simply, astounding. There is no singular and uncontested explanation. Rather, each country achieved its incredible mortality decline at different times, at different speeds and with (somewhat) differing determinants.

Measuring life expectancy is one way of capturing the mortality experience of a population. It also acts as a proxy measure for health more generally. Life expectancy is a sentinel measure of the social, political and environmental undercurrents in a society; it summarises the causes of disease and injury in a single number. Life expectancy takes account of the credits as well as the debits: it embodies all the behaviours, circumstances and interventions that promote health, or detract from it, in both the short and long run.

We are writing as Pkeh (non-Mori) epidemiologists and public health doctors. What interests us is the intersection of social history and medicine, the ways in which diseases are influenced by the environments that people live in, and the impacts of health services and other social interventions. We attempt to bring together biological explanations for ageing with an understanding of how changes in lifestyles and living conditions may affect population health. Coming from public health, we are particularly interested in the big picture view, in what is happening to whole populations.

This account foregrounds what can be measured and compared. Some might object: dont statistical trends provide a rather thin account of the lived experiences of growing up, ageing and dying in New Zealand? We disagree the statistics shed light on important questions of policy and practice. The archaic nature of present arrangements for superannuation, the future spend on health care, employment laws, how to share life opportunities more fairly, environmental constraints on human development, the complex relation of wealth and health, personal decisions on balancing work and other aspects of life a statistical history of life expectancy has something to say about all these matters, and more.

At a personal level, we all reflect from time to time on the number of years that we have left on this mortal coil. This value, the age an individual might live to, is easy to comprehend even if it is, usually, unknowable. At the level of a population, we can choose from a variety of aggregate measures. Life expectancy equates to the average age at death, or expected remaining number of years to live. (See text box opposite.) In this book we refer most commonly to life expectancy at birth, but it is possible to estimate the average years of life remaining at any age.