Newtown Park camp in Wellington, which housed the Second Contingent and elements of other contingents prior to their departure for South Africa. After rain, the camp became a muddy quagmire and in 1901 Volunteer corps members infuriated Premier Seddon by parading down Lambton Quay in a protest at the quality of camp rations. A LEXANDER T URNBULL L IBRARY , 1/1-006666-G

This book is dedicated to my wife, Cho Young-hae, whose unwavering support, encouragement and patience over many years has made it possible.

Contingent members ride onto Queens Wharf in Wellington to board their troopship for South Africa. A LEXANDER T URNBULL L IBRARY , 1/2-110815-F

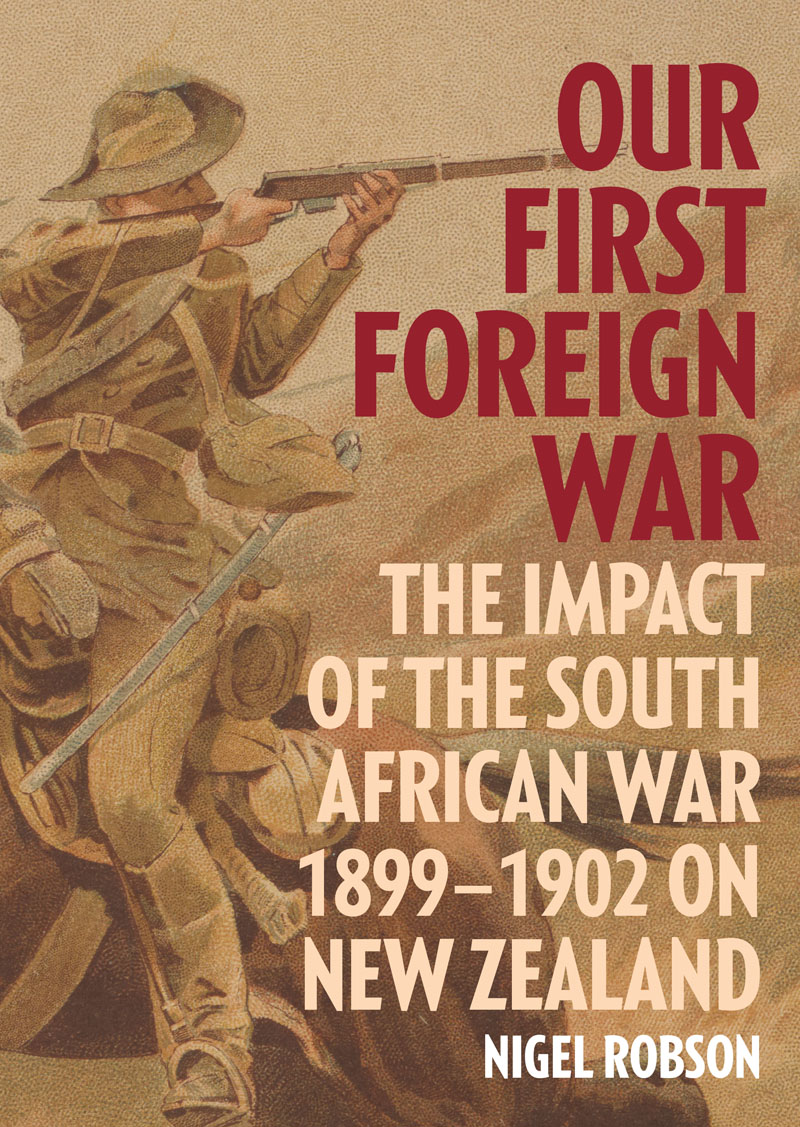

CONTENTS

1. The flag that floats over us

Patriotism and South Africa

2. Rally to the call of home and country

Domestic reaction to the war

3. An especially fine lot of fighting-men

The performance of New Zealand soldiers during the South African War

4. Loyalty to the British Empire

Mori responses to the South African War

5. Yelling yahoos in yellow

The behaviour of New Zealand soldiers during the South African War

6. Maimed, crippled and completely broken

The human cost of the war

7. These wars will always be popular

The economic impact of the South African War

PREFACE

O n a busy street in the Wellington suburb of Johnsonville, a wrought-iron street lamp stands incongruously as a reminder of a largely forgotten war. Awkwardly wedged between a medical clinic and a real-estate agent, its design is in stark contrast to the architecture of its surroundings. Although its concrete base is chipped, its marble tablet discoloured and its three original glass globes long ago replaced by a single four-sided lantern, the lamp nonetheless hints at its former grandeur. Its unveiling on an autumn day in 1905 presented a very different spectacle.

Arriving from the city by special train, Sir Joseph Ward, a senior Cabinet minister and member of the House of Representatives (MHR) for the Southland electorate of Awarua, addressed the crowd that had gathered for the occasion. While New Zealands governor, Lord Plunket, and Premier Richard Seddon forwarded their apologies for not attending, among those present were Defence Department officials, William Field, the MHR for taki electorate, the chairman and members of the Johnsonville Town Board, school cadets, and members of the public, including the parents and brother of Leonard Retter, the local blacksmith in whose honour the very handsome acetylene lamp paid for by public subscription had been erected.

Five years earlier and 11,000 kilometres away, war had broken out in South Africa. The conflict, which continued until 1902, pitted the combined military forces of the United Kingdom and contingents from other nations of the British Empire against those of the two Boer republicsthe South African Republic and Orange Free State. One of many young New Zealanders eager to take part, Retter enlisted in the Seventh Contingent in April 1901. Nine months later, he was among 23 Seventh Contingent men who lost their lives during a desperate Boer night attack on New Zealand positions on a hillside in Orange Free State.

It was the biggest single loss of life by New Zealand troops during the war, and its significance was reflected in the Johnsonville unveiling ceremony. Yet, today, comparatively few New Zealanders are familiar with what occurred at Langverwacht (or the Battle of Bothasberg, as it was then known), and most have little more than a cursory knowledge of the war in which it took place. In my own case, I have no clear recollection of when I first heard of the Boer War, as the conflict was commonly known during my childhood, but it was sometime in the late 1960s or early 1970s.

Once a week, my grandmother would visit our home and, if I was lucky, she would ask my mother to retrieve a battered leather suitcase from its place in a cupboard beyond my reach. Inside were the remaining possessions of her husband, a First World War veteran who had survived the horrors of the Western Front only to die in a car accident in 1941. Lifting the suitcases lid was like being transported back in time. Neatly arranged within were the three service medals of the grandfather I had never known, dulled by time, but still suspended from their brightly coloured ribbons. Beside them were a pair of enamelled cufflinks, bought in Egypt in 1916 and made in the form of sarcophagi, a faded French flag souvenired from a Paris street on Armistice Day 1918, and my grandfathers stitched Medical Corps Red Cross sleeve patch.

After my grandmothers death, I became custodian of the suitcases contents and, as time passed, slowly expanded the collection. At the time, it was not difficult to acquire military items brought back to New Zealand by veterans, but the oldest item in my collection came neither from France nor Egyptit was a book on the Boer War published in 1900. Its spotted pages featured patriotic engravings, including depictions of British soldiers gallantly taking Boer positions at the point of a bayonet. As a child, I considered neither the accuracy of the images nor the books repeated references to the Boer War, a title that both downplayed British involvement and implied that the responsibility for the death and suffering that occurred lay solely with South Africas Boer population. The war now goes by a number of names, but in an attempt to correct this bias I have chosen to refer to it simply as the South African War.

The Calvinist Protestant Boers were descendants of Dutch settlers who had emigrated from Europe to the Cape of Good Hope in the mid-seventeenth century and were later joined by French and German Huguenots. Although these settlers mainly spoke Dutch, over time the Boers developed their own language, Afrikaans, which combined Dutch with elements of other languages in the region. The early Boer settlers established Kaapkolonie (Cape Colony), which was administered for approximately 150 years by the Dutch East India Company. Concerned by the prospect of France securing a foothold in southern Africa, the British first took control of Cape Colony in 1795 following the Battle of Muizenberg, before returning it to the Boers in 1802 and then resuming control again in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

Although some Boers had moved northwards in the eighteenth century, in 1834 the British increased resentment among the Boers by abolishing slavery in the colony. This, together with the imposition of the English language and British law, saw thousands of disaffected Boers embark on Die Groot Trek (the Great Trek), a migration to the north-east. This took them into regions that were largely uninhabited due to what indigenous Africans call Mfecane (the scattering)the chaos and devastation caused by Zulu attacks on other African tribes living in the area. Nonetheless, the Boer migration increasingly brought them into contact, and sometimes conflict, with the indigenous African population. In 1843 the British annexed the Boer republic of Natalia, which became the British colony of Natal. In 1852 the Boers established the Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek (the South African Republic), followed by the adjoining Oranje Vrystaat (Orange Free State) in 1854.

Next page