Antonin Artaud

Titles in the series Critical Lives present the work of leading cultural figures of the modern period. Each book explores the life of the artist, writer, philosopher or architect in question and relates it to their major works.

In the same series

Antonin Artaud David A. Shafer

Roland Barthes Andy Stafford

Georges Bataille Stuart Kendall

Charles Baudelaire Rosemary Lloyd

Simone de Beauvoir Ursula Tidd

Samuel Beckett Andrew Gibson

Walter Benjamin Esther Leslie

John Berger Andy Merrifield

Jorge Luis Borges Jason Wilson

Constantin Brancusi Sanda Miller

Bertolt Brecht Philip Glahn

Charles Bukowski David Stephen Calonne

William S. Burroughs Phil Baker

John Cage Rob Haskins

Albert Camus Edward J. Hughes

Fidel Castro Nick Caistor

Paul Czanne Jon Kear

Coco Chanel Linda Simon

Noam Chomsky Wolfgang B. Sperlich

Jean Cocteau James S. Williams

Salvador Dal Mary Ann Caws

Guy Debord Andy Merrifield

Claude Debussy David J. Code

Fyodor Dostoevsky Robert Bird

Marcel Duchamp Caroline Cros

Sergei Eisenstein Mike OMahony

Michel Foucault David Macey

Mahatma Gandhi Douglas Allen

Jean Genet Stephen Barber

Allen Ginsberg Steve Finbow

Ernest Hemingway Verna Kale

Derek Jarman Michael Charlesworth

Alfred Jarry Jill Fell

James Joyce Andrew Gibson

Carl Jung Paul Bishop

Franz Kafka Sander L. Gilman

Frida Kahlo Gannit Ankori

Yves Klein Nuit Banai

Akira Kurosawa Peter Wild

Lenin Lars T. Lih

Stphane Mallarm Roger Pearson

Gabriel Garca Mrquez Stephen M. Hart

Karl Marx Paul Thomas

Henry Miller David Stephen Calonne

Yukio Mishima Damian Flanagan

Eadweard Muybridge Marta Braun

Vladimir Nabokov Barbara Wyllie

Pablo Neruda Dominic Moran

Georgia OKeeffe Nancy J. Scott

Octavio Paz Nick Caistor

Pablo Picasso Mary Ann Caws

Edgar Allan Poe Kevin J. Hayes

Ezra Pound Alec Marsh

Marcel Proust Adam Watt

John Ruskin Andrew Ballantyne

Jean-Paul Sartre Andrew Leak

Erik Satie Mary E. Davis

Arthur Schopenhauer Peter B. Lewis

Adam Smith Jonathan Conlin

Susan Sontag Jerome Boyd Maunsell

Gertrude Stein Lucy Daniel

Igor Stravinsky Jonathan Cross

Leon Trotsky Paul Le Blanc

Richard Wagner Raymond Furness

Simone Weil Palle Yourgrau

Ludwig Wittgenstein Edward Kanterian

Frank Lloyd Wright Robert McCarter

Antonin Artaud

David A. Shafer

REAKTION BOOKS

For Selma Selmanagi

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448, Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2016

Copyright David A. Shafer 2016

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements

match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Bell & Bain, Glasgow

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780236018

Contents

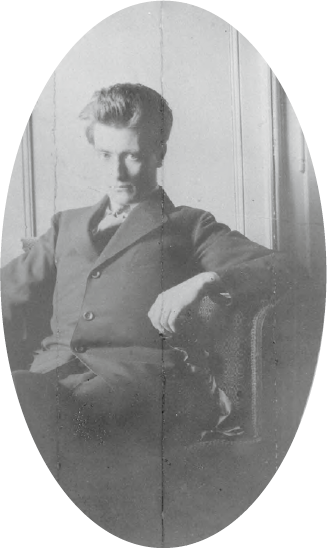

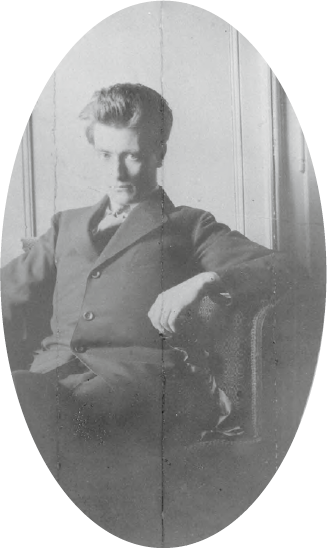

Antonin Artaud photographed in 1920, in the consulting room of his psychiatrist Dr Toulouse.

Introduction

In an interview from 1996, the French cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard averred, Everyone should have a singular, personal relation to Artaud. With him, we are always on a very inhuman level. He has become an impersonal being. What Baudrillard appeared to be saying is that the departure of the corporeal Artaud has led to a transubstantiated reversal; in the process, Artaud has achieved almost mythological status, a conclusion echoed by others, including those closest to Artaud. In April 2012 Artauds nephew, Serge Malaussna, his last living relative, alluded in conversation with me to the existence of two Artauds: the one who lived and the one of our ideas. In other words, Artaud has become something of a palimpsest upon which we inscribe what we want to find in him, and maybe even find in ourselves.

In some respects, Artaud facilitated this in a couple of ways. First, his choice of literary expression was compelling, and at the same time it was head-spinningly confusing. Much of what he wrote was in the service of transcending the boundaries of conventional communication: a cocktail of obtuse symbolism, intentional obfuscation, sexual prudery and weird scatological analogies, followed by references to curses and spells as a chaser and yet, this strange admixture was so well written. Second, in a paper he wrote to accompany an exhibition he organized on the work of the Mexican Surrealist Mara Izquierdo, Artaud noted that, as they travel, objects exchange their properties and metamorphose. Why would it not be the same for him that his peregrinations, whether within this dimension or after his death outside of it, have caused a corresponding alteration of his persona?

It is pretty clear that Baudrillard had no intention of wiping away the occluding mud Artaud seemingly placed intentionally on the window into his thoughts, and I must concur that to study Artaud means respecting the impenetrability of his seemingly Kevlar-shrouded head; but all the same, the more I read, the more I began to find a logic to his thoughts. For purposes of literary clarity, the pre-asylum Artaud is a snap in comparison to the guy who, during nearly a decade of confinement in French insane asylums, had existed alone, in his head. Whether or not he was insane when first institutionalized in 1937, his years in the precariousness of wartime French asylums did no favours to his mental health. The electroconvulsive therapy administered to him in Rodez during the last years of his confinement might have rewired him and prepared his re-entrance into society; but to Artaud this was yet another example of the individuals vulnerability to envotements (spells). While it is tempting to put these references to spells down to his penchant for spiritualism, given the impact of hegemonic forces on him, how else could Artaud make sense of it all?

From start to finish, there is constancy to Artauds writings and ideas; they scream (sometimes literally) alienation and rebellion: rebellion against the stultifying bourgeois values of his youth; the privileging of Western cultural norms, including reason and rationality; and rebellion against the authorities; the power of wealth; and the subversion of nature. Stripped of their bizarre, if not inaccessible, symbolism and verbiage, Artauds ideas are consonant with the ideals of the French revolutionary tradition, challenging domination in general, and bourgeois domination in particular; but whereas nineteenth-century French revolutionaries situated their challenge in the socialpolitical realm, Artauds revolution was over the cultural space of meanings, understandings, representations and signs.