Illustrations

(Following the main text)

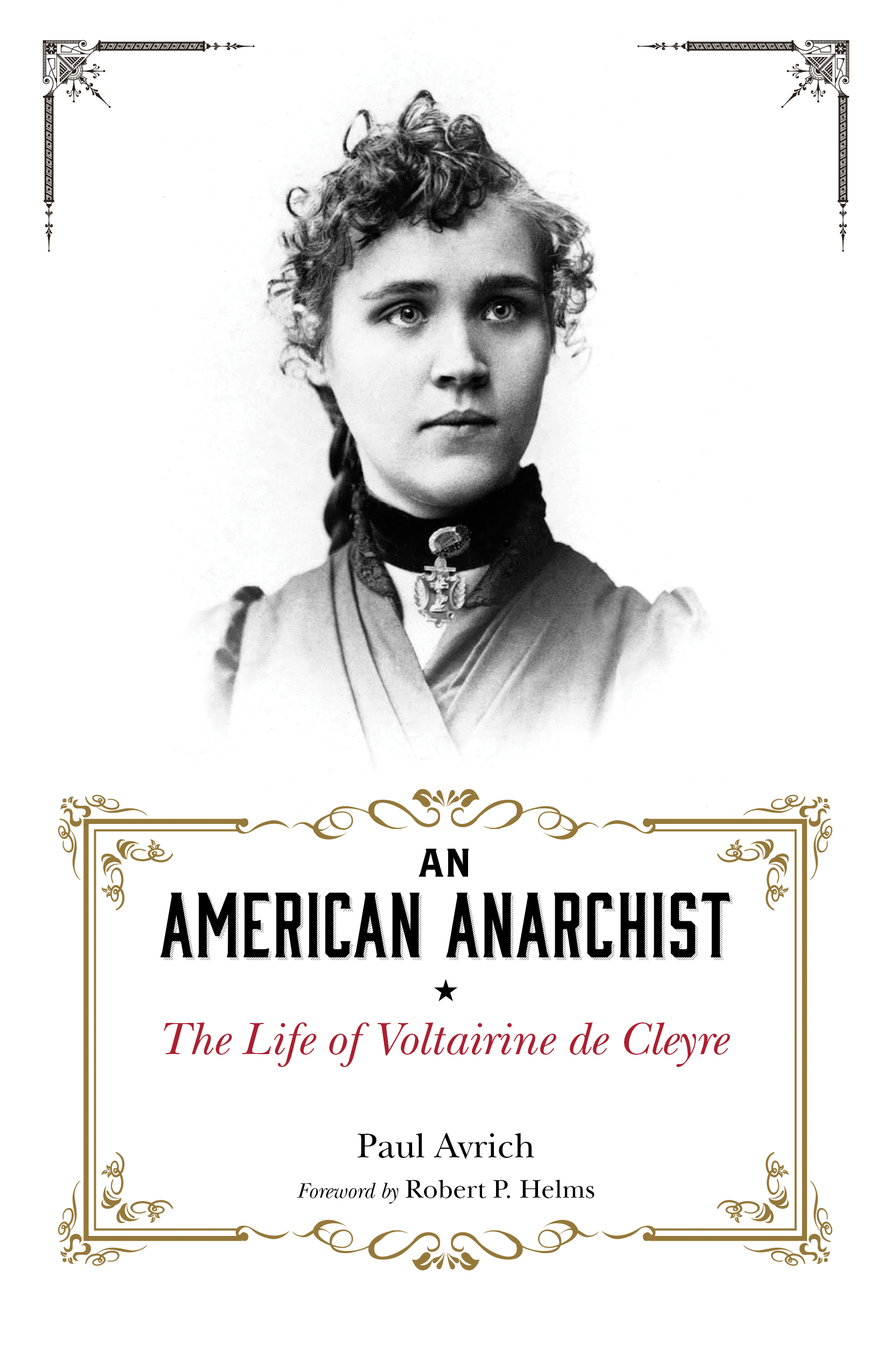

1. Voltairine de Cleyre, Philadelphia, Christmas 1891. Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Research Center)

2. Harriet Elizabeth De Claire. Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Research Center)

3. Dyer D. Lum ( The Freethinkers Magazine , August 1893). Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Research Center)

4. James B. Elliott and Harry de Cleyre. Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Research Center)

5. Johann Most (International Institute of Social History)

6. Harriet Elizabeth De Claire, St. Johns, Michigan. Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Research Center)

7. The Haymarket Martyrs. Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Research Center)

8. Lucy Parsons. Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Research Center)

9. The Haymarket Monument at Waldheim Cemetery (Chicago History Museum, ICHi-037013)

10. Benjamin R. Tucker, Boston, c. 1887. Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Research Center)

11. Voltairine de Cleyre, London, 1897 (Ishill Papers, University of Florida)

12. Peter Kropotkin (Bund Archives)

13. Thomas H. Bell, 1888 (Courtesy of Marion Bell)

14. Voltairine de Cleyre, Philadelphia, August 1898, taken by her sister Adelaide. Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Research Center)

15. Voltairine de Cleyre, Philadelphia, 1901. Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Research Center)

16. Leon Czolgosz, Buffalo, 1901 (Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society)

17. Alexander Berkman, 1892. Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Research Center)

18. Emma Goldman, St. Louis, 1912 (International Institute of Social History)

19. Letter of Voltairine de Cleyre to Alexander Berkman, August 7, 1906 (International Institute of Social History)

20. Saul Yanovsky, New York, c. 1910 (Courtesy of Eva Brandes)

21. Yiddish manuscript by Voltairine de Cleyre. Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Research Center)

22. Flavio Costantini, Francisco Ferrer. Barcelona, October 13, 1909 (Courtesy Archivio Flavio Costantini)

23. The Modern School by Francisco Ferrer, translated by Voltairine de Cleyre in 1909 (Tamiment Collection)

24. The Philadelphia Modern School, Radical Library, 1910 or 1911 (Courtesy of Harry and Celia Melman): Mary Hansen (center, holding girls arms), George Brown (right, holding boy), Joseph Cohen (next to Brown, with daughter Emma in front)

25. Harry Kelly, 1922 (International Institute of Social History)

26. Leonard Abbott, New York, c. 1905. Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Research Center)

27. Ricardo and Enrique Flores Magn (International Institute of Social History)

28. Voltairine de Cleyre, Chicago, 1910 ( In Memoriam: Voltairine de Cleyre , Chicago, Annie Livshis, 1912)

29. Voltairine de Cleyre Memorial, Radical Library, Philadelphia, June 23, 1912. Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Research Center)

Foreword to the 40th Anniversary Edition of An American Anarchist

In 1990, I walked into a tiny anarchist bookstore and found a rare copy of An American Anarchist: The Life of Voltairine de Cleyre by Paul Avrich. I knew de Cleyre only as a figure mentioned in Avrichs later book The Haymarket Tragedy . Because I relished Avrichs writing already, because I had the enthusiasm of a recent convert to anarchist thinking, I could hardly wait to read de Cleyres biography.

Avrich presented to his readers the depth and intensity of this intellectual powerhouse who repeatedly made sacrifices and endangered herself in order to stay true to her principles, which she never once compromised for her own safetys sake. De Cleyre pressed her cause when anyone else would have dropped the activism due to poverty and sickness. No one, living or dead, could introduce her as well as Paul Avrich does with this biography, which is as inspiring to readers as Emma Goldmans Living My Life or Ursula Le Guins The Dispossessed . Avrichs books are as readable as novels, and de Cleyres life is what youre about to discover.

De Cleyre remains today one of the most inspiring of all the early-American anarchists, including the notorious few, such as Emma Goldman or Johann Most, and the less known but equally remarkable, like educator Joseph J. Cohen, editor Abraham Isaak, or the almost completely forgotten poet-essayist Viroqua Daniels.

In contemporary descriptions, Voltairine de Cleyre is striking for her intellectual powers, her intense empathy and love for suffering people and animals, and her particular charisma. Her writings carry the entire range of human experience curiosity and profound wonder in her earlier years, then more sorrow and bitterness as she grew older. In an interview, Avrich said de Cleyre was a fascinating person. I read her poetry and stories and found a sadness in her. He succeeded in rescuing this brilliant and compelling person from near non-existence, and because of his work we too are moved by her words, we imagine her voice and self, and we are energized by her courage.

Paul Henry Avrich was born in Brooklyn, New York on August 4, 1931, growing up in the Crown Heights neighborhood with his sister Dorothy. His parents, Murray, the owner of a small dress manufacturing company, and Rose Zapol Avrich, were Jews who had emigrated from Odessa. Avrich was educated in public schools and completed a Bachelor of Arts degree at Cornell University in June 1952, having started there at age sixteen on a scholarship. He then joined the military, which sent him to Syracuse University to study Russian.

In 1959, Avrich was one of twelve American students chosen to go to Russia in a special exchange program, and he spent three months in the archives of the Lenin State Library in Moscow, reading the records of factory workers committees and the sailors uprising at Kronstadt. Here was where he first discovered anarchism, and these early research endeavors in Moscow developed into his doctoral dissertation at Columbia University and then into his pioneering books, The Russian Anarchists, The Russian Rebels , and Kronstadt 1921, which are still definitive texts on anarchism in Russia. Avrich began teaching at Queens College of the City University of New York in 1961 and remained there until his retirement in 1999. Karen Avrich describes her father as an intensely disciplined man, working seven days a week, usually in his small study at the back of the family apartment on Riverside Drive. It was a somewhat Spartan space, holding a plain desk, piles of books and files, and stacks of yellow pages covered in his slanting, looping longhand. There was no television or radio playing, no art on the walls; the window looked out onto a glum section of courtyard. The only occasional distraction, a cat sprawled across the desk, tail swishing deliberately through sheaves of paper.