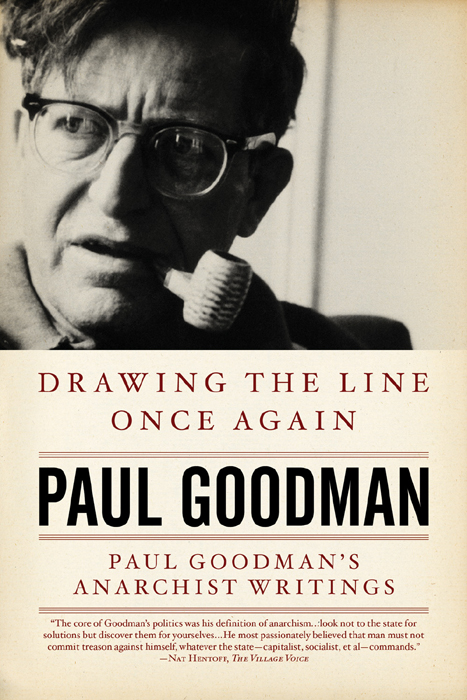

Drawing the Line Once Again

Paul Goodmans Anarchist Writings

Paul Goodman

Edited by Taylor Stoehr

Drawing The Line Once Again: Paul Goodmans Anarchist Writings

Drawing The Line Once Again 2010 by Sally Goodman

Introduction 2010 by Taylor Stoehr

This edition 2010 by PM Press

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted by any means without permission in writing

from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-60486-057-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2009901375

Cover: John Yates

Interior design by briandesign

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PM Press

PO Box 23912

Oakland, CA 94623

www.pmpress.org

Printed in the USA on recycled paper.

Contents

Preface

W hen I met Paul Goodman in 1950 I was eighteen, and he was thirty-nine. I was a callow youth from the Midwest, much in need of mentoring, and he was a bohemian guru with a little band of disciples already following him around, and the author of many books, some of them still to be in print half a century later. I saw Goodman only five or six times that spring before going back to Omaha, but for the next ten years he did guide me, at first in a few crucial letters of advice, then only through his writings, which I began to collect and study in a way that I studied nothing else.

I say this to orient new readers of Goodman, some of whom I assume will be at the age I met him and perhaps as much in need of counsel as I was. Although it weighed heavily in my own case to have met him in the flesh, what ultimately counted most, both then and later in the 1960s when I reconnected with him, was not his physical presence but his lucidity and common sense. He used to say it was the obvious that people never seemed to notice, plain as the nose on your face. That was what was so irresistible about him. As if in dialogue with Socrates, you felt you were in touch with your own wisdom, like a kind of memory, for the very first time. Our mutual friend George Dennison once said that he was an angel of mind whose feats of memory and analysis seemed like familiar descriptions of a much-loved home.

Goodman had no charisma, whether face-to-face or in front of a faceless audience. But you soon forgot about the figure he cut, because his words lit up your own mind, you listened and you were thinking those thoughts yourself. They were rarely something youd want to write down or memorize. For me and others who gathered round him in those days there was no lesson to be learned and stored away, rather an attitude toward life and the world. You could get it into your own bones. And because writing is a way of thinking, and he was a writer to the core, you could get it by reading his books. I have met many other people who had the same experience, including not a few who never laid eyes on him.

There are several avenues by which one might approach what I am calling Goodmans attitude. It was the primary tendency in the Gestalt therapy he was just beginning to practice at the time I met him, and was also at the heart of the artists life he had chosen for himself. For me, however, Goodmans anarchism best exemplifies this deep-going attitude. I have included two succinct summaries of it in the pages that follow The Anarchist Principle and Freedom and Autonomy but to get the feel of this habit of mind, which he sometimes called the habit of freedom, I suggest reading through the more expansive essays printed here. As he believed, character is revealed in a writers style, expressed in the very rhythms of speech, and of course character is the source of any deep-going attitude.

Curiously, one finds in these longer selections a number of passages where Goodman repeats himself, not merely in idea or attitude but verbatim, quoting himself without quotation marks, as if it couldnt be said better than he had already said it a trick he developed early in his career, along with footnotes referring readers to his other writings. In later years such cloning was helpful in meeting multiple demands on him from editors and publishers, but it also highlights what Im trying to get across here: once we are familiar with his voice, everything Goodman says seems reminiscent of some other portion of his work. Havent I read this paragraph before? Goodmans tone changed dramatically after 1960, once he was no longer writing only for his friends in the San Remo bar, but his attitude remained the same throughout the twenty-five years represented by these essays. Near the end of his life he said that he hadnt changed his political ideas since I was a boy. This was true.

My own earliest encounter with the anarchist attitude came by reading The May Pamphlet side by side with its imagined spelling-out in The Dead of Spring, an expressionist novel he published in 1950. When Goodman gave me a copy, hot off Dave Dellingers Libertarian Press, I didnt realize what a providential act that was to be. I was a baffled teenager stumbling through the rites of adulthood in the U.S.A. smoking, driving, drinking, punching a clock, matriculating, marrying, and wearing a uniform for me, in that order. The hero of The Dead of Spring was working his way through different rites of passage, but in the end he arrived at the same crisis, what Goodman called The Dilemma, formulated by the Prosecuting Attorney at Horatios trial for Treason Against the Sociolatry:

You have tried to live as if our society, the society of almost all of the people, did not exist. [O]ur society is the only society that there is in what society can you move if not in our society? If one conforms to our society, he becomes sick in certain ways. But if he does not conform, he becomes demented, because ours is the only society that there is.

In 1950, I was too nave to truly comprehend what the opposite crime, treason against natural societies (as it was termed in The May Pamphlet), might mean for someone setting out on these paths, but what I did intuit, almost wordlessly, was that the world I was entering was founded on lies and hypocrisy. Much as I loved my home and the family friends, teachers, and neighbors I knew as a boy, I was aware that almost every adult I met was masked, and no matter how smiling a face might be put on it, their lives were venal and empty. In The Dead of Spring, Goodman had called their condition The Asphyxiation. I had gotten a strong whiff of that self-betrayal festering in my parents generation and was afraid that I, too, was infected.

Goodman amazed me because he did not live this way. As far as I could tell, he had no secrets, no reticence, no shame. Whatever scary implications such an open life might have for a shy and embarrassed young fellow like myself, it was better than suffocation in conformity and complacency. There was another way to live one that presented something to believe in, pursuits to follow wholeheartedly, countering the fear that there was nothing worth doing.

I began by paying attention to how he behaved in his family, among his friends, in public spaces, and face-to-face with me, but it was not until I had returned to the Midwest and read The May Pamphlet and The Dead of Spring that I had any insight into what had bowled me over during our initial encounter. My misgivings about the adult world were embodied in what he called treason against natural societies: every one knows moments in which he conforms against his nature, in which he suppresses his best spontaneous impulse, and cowardly takes leave of his heart. It was precisely such moments of self-betrayal that had led to the great wars of the century, long prepared in the averted eyes and uneasy smiles of parents whose children would die in them.