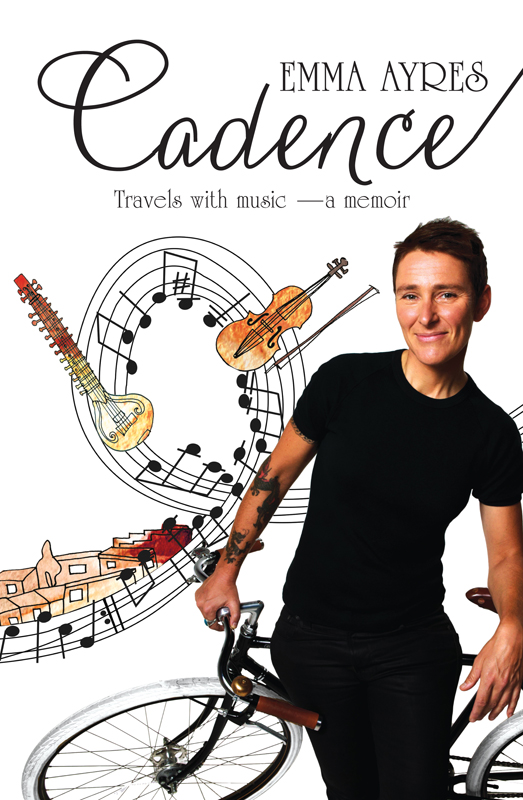

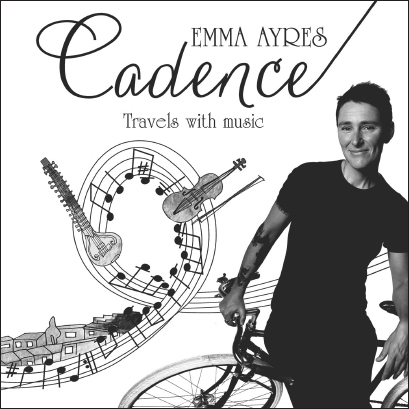

Emma Ayres is a graduate of the Royal Northern College of Music, where she won prizes for chamber music and viola, the Royal Academy of Music and the Hochschule der Knste in Berlin. She has studied with members of the Amadeus Quartet, William Pleeth, Simon Rowland-Jones and Bruno Giuranna.

After playing the viola professionally for ten years, Emma began her radio career in 2001. She worked initially at Radio Television Hong Kong, and after immigrating to Australia in 2003 joined ABC Classic FM. She still plays her viola, and has recently played with the Bombay Chamber Orchestra and the Afghan Youth Orchestra, about which she has made two radio documentaries.

When I was eight years old, my mother asked me the most important question of my life.

Emma, what instrument do you want to play?

A simple question: what sounds do you like? What do your friends play? Who is your favourite music teacher at school? Do you, in fact, particularly care what instrument you play? Or will it simply be a way of passing the time until you find something else to distract you?

Or a question of great depth and difficulty, one that you may not ever be able to answer, a koan; you may as well ask, what language would you like to speak for the rest of your life? What type of people will your friends be? What will evolve to be your fundamental philosophical tenets? Who, indeed, do you want to be in this world?

Seeing as I was only eight, I thought the question was the former.

I want to play the cello.

My mum put me down for the violin.

I hated the violin. My second sister Penny played it and my mum Anne had played it until she was sixteen, when she sold her instrument to buy make-up; the two of them fought bitterly over how long Penny should practise and in my childs mind the violin and the shrillness it brought were hideous.

Most importantly, the violin was not the cello. Jacqueline du Pr played the cello, Mr Fairbanks, the cool teacher at school with the corduroy trousers and the big beard, played the cello; I wanted to join them and play the cello too, I wanted to be the source of its sound. My desired instrument ended up in the hands of my older brother Tim. He gave up after a year.

In England in the late seventies there was a network of peripatetic music teachers who travelled around in each county teaching groups and individuals, all for free. Then, when you could read music and had maybe passed a couple of exams, you could go along and play with the youth orchestra of your standard and start to swim in the universe of music and musicians.

My first violin teacher was Mrs Llewellyn. Every week at school she taught three of us children together, for half an hour. If my own gatekeeper was anything to go by, this musical universe was an eccentric place indeed; Mrs Llewellyn was an extremely tall woman, in her sixties and already bowed with scoliosis, draped with numerous shawls and hair fraying from her thinning bun. I would later go to her home for lessons where she kept a silent husband, a cat called Yorick and a spotty son who played the organ. She was mostly kind, suddenly mean and in that first lesson taught us how to read the notes in manuscript for the four open strings of the violin. G, down the bottom with two extra lines because it is SO low; D, hanging out underneath the stave for shelter; A, all relaxed in the middle and looking up to E, perched on top and very, very screechy. E for screechy.

Afterwards I walked home proudly across the fields with my own violin; well, it belonged to the school, but I didnt care. I also didnt care about the cardboard case, which was falling apart, and the crude instrument and bow, which had been made by Mr and Mrs Skylark in China. And at the time I didnt care that it was not a cello. All I knew was that I had a friend forever.

It was a Friday, which meant Granma would be coming round for dinner. We had fish on Fridays. Casserole on Saturdays, roast something on Sundays, cold roast on Mondays, mince on Tuesdays, sausages on Wednesdays (those two could be swapped), liver on Thursdays and fish on Fridays. Granma came for the fish and the roast. The six of us in our permanently allotted chairs ate dinner silently and afterwards I showed Granma my violin.

Can I play you something, Granma?

No, you cant play anything. You havent learnt to play anything yet.

My mothers brutal reminder had nothing to do with grammar. My first performance and my enthusiasm were shattered before I could even begin. I put my violin back in its case to wait for a time when I could play something.

Perhaps this is a good point at which to state quite bluntly that my childhood was desperately unhappy. I was that child who sat at the edge of the group. Fat, frowning, silent, uncertain and, most important to other children, unhappy-looking. And therefore picked on.

So the fat: well, puppy fat, never mind. But the frowning, that came from an early need to try to work out where happiness lay. It didnt visit us at home very much. There was the small issue of my parents divorce when I was two, after which Anne had had a nervous breakdown and John Ernest George had married the next-door neighbour and moved to Singapore. In the space of two years Mum had gone from being a married, privileged expatriate living in Nigeria, with servants, games of bridge and drunken curry lunches, to working part time as a civil servant and looking after four children (with only four and a half years between us) in the middle of England in a small, dull town. Happiness doesnt have much room to manoeuvre in such conditions. There was a lot to frown about.

The silence was simply a survival mechanism. What does an animal do when all around is doubt, insecurity and risk? It keeps a low profile. My poor mother had the most desperate moods, as she tried to bring us up with only her parents help, very little money, no friends and an enormous, rejected love that would not sit down and surrender. Dad came and visited once a year, for a day. For appearances. That eventually drifted off to maybe once every few years. But still, he was the man, he was the cool guy with loads of money, presents, a car (we never had one) and a day of fun. He never sent birthday or Christmas cards on time, but isnt it extraordinary how full of faith a child can be? My birthday is in February and every morning I would hope that a card might be shoved through the letterbox with one of those exotic Singaporean stamps on it. Id wait until about November, and then start to look forward to Christmas instead. I didnt give that up until I was thirty, when my brother Tim told me that Dad said he couldnt be bothered to call on my birthday. Twenty-eight years. I gave it a good go.

I eventually worked out that if Mum were in a good mood in the morning, she certainly wouldnt be by the evening. In her wretchedness to try to keep things together, we had an order for everything. In the morning we would get up, stand in a line at the top of the stairs and go down, still in line, and have a hot drink. Then, as we took it in turns to wash or be washed, the others would make beds and get dressed. Then we would line up again Liz, Penny, Tim and me in order of age, to have our hair brushed. Breakfast was cooked, always (no tatty cardboard food in our house), and then we walked over the playing fields and railway line to school. We were the only children we knew who came from a so-called broken home. Our home wasnt broken, it was crushed. Crushed by everybody in it wanting to be somewhere or someone else.