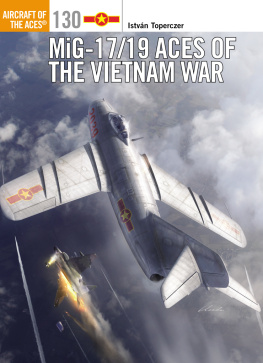

This book is dedicated to the memory of MiG-17 ace Luu Huy Chao (1936-2014)

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by Osprey Publishing

PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK

1385 Broadway, 5th Floor, New York, NY 10018, USA

E-mail:

This electronic edition published in 2016 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Bloomsbury is a registered trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Osprey Publishing, part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

2016 Osprey Publishing Ltd.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-4728-1255-1 (PB)

ISBN: 978-1-4728-1257-5 (eBook)

ISBN: 978-1-4728-1256-8 (ePDF)

Edited by Tony Holmes and Bruce Hales-Dutton

Cover Artwork by Gareth Hector

Aircraft Profiles by Jim Laurier

Osprey Publishing supports the Woodland Trust, the UKs leading woodland conservation charity. Between 2014 and 2018 our donations will be spent on their Centenary Woods project in the UK.

www.ospreypublishing.com

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.ospreypublishing.com. Here you will find our full range of publications, as well as exclusive online content, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters. You can also sign up for Osprey membership, which entitles you to a discount on purchases made through the Osprey site and access to our extensive online image archive.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

T his book is about the young Vietnamese airmen who demonstrated extraordinary courage in aerial combat during the 1960s and early 1970s. They fought a powerful and highly trained enemy and the success they achieved enabled a relatively small number to achieve five or more aerial victories and become acclaimed as aces. But how were these young pilots able to acquire and demonstrate the skills, as well as the physical and mental qualities, needed to achieve such success against a well-equipped and technically advanced foe?

Many began their military service between the ages of 18 and 20. After the rigours of pilot selection and flying training they were between 25 and 30 by the time they reached operational units. These men were immediately involved in aerial combat, which meant that those individuals who survived their early encounters with a dangerous enemy were able to rapidly develop situational awareness, combined with both daring and restraint, to allow them to build up their scores. On both sides there was a mix of experienced and rookie pilots, and when it came to aerial success much depended on being in the right place at the right time. Ultimately, the outcome of the battles fought in North Vietnamese airspace demonstrated once again that there was no substitute for the ability to swiftly size up a situation and act accordingly.

During the Korean War of 1950-53, MiG-15 fighters had operated in North Korean markings from Chinese airfields north of the Yalu River that were declared off-limits to US pilots. When the communist jets came south of the Yalu, however, they were fair game for USAF F-86 Sabres. American fighter squadrons were duly credited with at least seven MiG-15s for every F-86 that was lost. Many of the Sabre pilots were World War 2 veterans who proved to be better trained and more experienced than their Soviet, North Korean and Chinese opponents.

A decade later, North Vietnamese pilots found themselves overwhelmingly outnumbered by modern American aircraft, many of which were again flown by experienced combat veterans. Yet even though the MiG-17s operated by the Vietnamese Peoples Air Force (VPAF) were hardly in the first flush of youth, the design being based upon that of the MiG-15 which had fought in Korea, they were still able to offer a surprisingly stern challenge to the intruders. The gradual escalation of the US bombing campaign gave the MiG pilots the opportunity to gain experience, and they were buoyed by their early successes.

The VPAFs aerial combat strategy was based on an intriguing blend of Soviet technology and the guerrilla tactics so effectively used on the ground by communist forces. This involved close cooperation between VPAF pilots and Ground Control Interception (GCI) and, later, surface-to-air missile (SAM) and anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) units. As a result, American F-4 Phantom II, F-8 Crusader and F-105 Thunderchief crews often had to contend with both SAM and AAA fire before being attacked by North Vietnamese MiGs. US pilots had been trained to believe that aerial warfare would involve radar-guided missile engagements fought beyond human sight at speeds of around Mach 2.0. Now, however, they were having to adjust to a dangerous close-range environment that favoured the quick and the nimble. And it was the MiG-17 with its superior manoeuvrability and turning ability that excelled at the low altitude close-range ambushes and subsonic dogfights that were the hallmarks of the air war over North Vietnam.

Paradoxically, the North Vietnamese were not fully able to exploit the tactics they were forcing their opponents to adopt. Although the VPAF pilots Soviet and Chinese mentors had clearly learned lessons from the Korean War, North Vietnamese pilot training was never as consistent as that available to their Americans opponents. And there were two further handicaps. VPAF pilots were closely linked to their GCI command posts, restricting initiative in the face of the unexpected. And tactics changed from day to day, which confused and hindered the less-proficient North Vietnamese pilots as much as it did the Americans.

From the start, however, the MiG pilots harboured few illusions about their capability and limitations. They knew they lacked the aircraft to waste in fighter-versus-fighter duels so they adopted hit-and-run tactics. As the war unfolded they quickly learned important lessons and were able to develop their tactics accordingly.

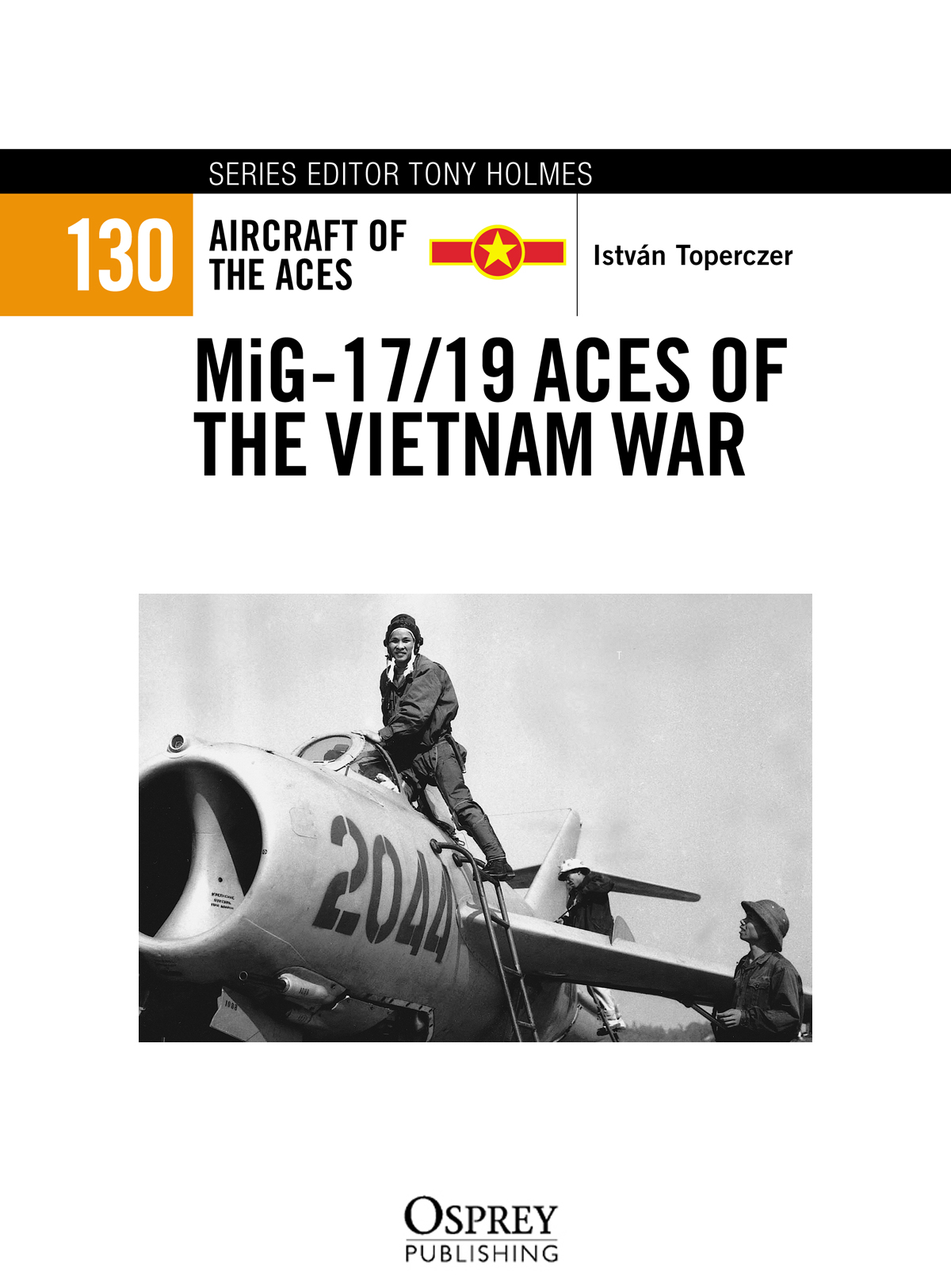

The VPAF created its first MiG-17 unit, the 921st Fighter Regiment (FR), on 3 February 1964 after its pilots had received training in China. The second unit, the 923rd FR, followed on 7 September 1965. In February 1969, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) decided on the creation of the 925th FR to be equipped with Chinese-built MiG-19 fighters. These three units played a major role in the war, as well as helping their pilots to develop the qualities needed to become aces between 1965 and 1972.

The North Vietnamese MiG-17 aces came from different generations and were active during different periods of the air war. During 1966-67, the group of MiG-17 pilots that comprised Le Quang Trung, Nguyen Van Bay, Luu Huy Chao and Vo Van Man achieved the five victories qualifying them as aces in 12 to 24 months. The next generation, with pilots like Nguyen Phi Hung and Le Hai, was able to reach the same status in six to 12 months during 1967-68.

The MiG-17 aces claimed a combined total of 34 aerial victories, comprising eight F-105 Thunderchiefs, 16 F-4 Phantom IIs, seven F-8 Crusaders, two C-47s and an AQM-34 Firebee drone between 1965 and 1972. Although three MiG-17 pilots Phan Van Tuc, Bui Van Suu and Hoang Van Ky did not manage to achieve the five aerial victories to qualify them as aces, they were collectively responsible for a further 12 American losses.

Next page