CONTENTS

THUNDERCHIEF

W hen the United States intervention in Laos and Vietnam gathered momentum in 1965 the Republic F-105 Thunderchief was the USAFs primary fighter-bomber, having by then entered service with 24 operational squadrons and five training units. The aircraft had originally been purchased as an all-weather strike fighter, delivering tactical nuclear weapons and fighting its way past enemy interceptors on the return journey if it survived the multiple nuclear detonations caused by many similar aircraft. For this mission it had an internal bomb-bay (unlike other contemporary fighters) and a 20 mm rotary cannon, and AIM-9B Sidewinder missiles could also be carried for self-protection.

The F-105s prolonged development delayed its initial operational service until January 1959, but by 1964 it was well established in frontline USAF nuclear alert squadrons in Europe and the Far East. Single-seat versions remained in production until January 1965.

An initial contract for 199 F-105As was awarded in September 1952 and the prototype made its first flight on 22 October 1955. The first two YF-105As flew with interim Pratt & Whitney J57-P-25 engines, but the third prototype and all subsequent F-105s had Pratt & Whitneys J75, which developed up to 26,500 lbs of thrust with afterburner and air-cooling water injection. The J75 made the aircraft the largest and most powerful single-engined fighter of its time. In combat this powerplant was the core of the F-105s success, excelling in reliability and enabling the aircraft to outdistance any rival fighter at low altitude thanks to the jets top speed of 700+ mph. It also gave the aircraft enough muscle to haul 5000 lbs of ordnance and 900 gallons of externally-carried fuel over a 650-mile combat radius. The F-105s large fuel capacity did, however, pose limitations in combat, as a 388th Tactical Fighter Wing (TFW) pilot noted. You are either too heavy with fuel to be manoeuvrable or too short on fuel at fighting weight to make it back home successfully.

Although overall weight in the final operational version (the F-105G) reached 54,600 lbs, the aircraft still used the same engine. And although the J75 developed tremendous power, the Thunderchiefs acceleration from low speed in combat was comparatively slow unless the pilot nosed over into a dive. The F-105 also bled off speed very rapidly in a turn or steep climb.

Chief designer Alex Kartveli, creator of the P-47 Thunderbolt, designed a 63-ft long fuselage for the first production model, the F-105B, using semi-monocoque construction and area-rule to reduce transonic drag. It contained a pressurised cockpit, gun installation, avionics, a 16-ft long weapons bay, fuel tanks and the massive engine and afterburner. Four-petal extending airbrakes were installed at the rear to slow the aircraft for weapons delivery or to enable safe aircrew ejection. The two side petals extended as airbrakes for landing, although a 20-ft diameter ring-slot braking parachute provided most of the retarding force after touchdown. The F-105s fairly conventional structure used panels that were milled to the exact thickness required for optimum strength and lightness.

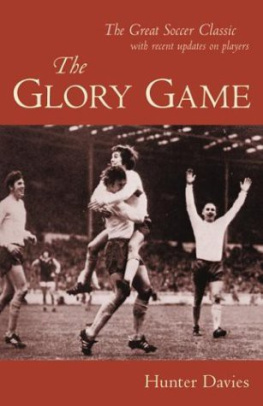

Wearing the yellow tail band of the Kadena-based 18th TFW, which detached Thunderchiefs from its 12th, 44th and 67th TFSs to Korat from February to October 1965, these F-105Ds carry M117 bombs (foreground) and AGM-12B Bullpup missiles for a North Vietnam strike. Seen here furthest from the camera, F-105D 62-4284 became a triple MiG killer in 1967, with two victories being credited to Capt Max Brestel and a third to Capt Gene I Basel. The nearest aircraft (62-4231) was shot down by an SA-2 on 27 October 1967 during the same mission on which Capt Basel claimed his MiG-17. One of four F-105D casualties that day, Col John Flynn, leading the mission as 388th TFW vice-commander, was rolling into his bombing dive on the Canal des Rapides Bridge when the missile struck 62-4231 (USAF)

The wing, swept at 45 degrees, was 385 square ft in area small for such a large airframe and thin for high speeds. It provided stable, fast flight at low altitudes for the tactical nuclear mission in which turning performance was not a priority. However, the wing inevitably limited the F-105s ability to tackle much more manoeuvrable opposition such as the MiG-17s that it would fight over North Vietnam. As one 355th TFW pilot noted ruefully, air-to-air combat is still a turning game. The airplane that turns the best has the advantage.

In order to provide clearance on rotation for the ventral fin beneath the rear fuselage the wing was mid-mounted, requiring a long, stalky undercarriage. This gave marginal clearance for a multiple ejector rack (MER) with up to six 750-lb bombs or a 450- or 650-gallon fuel tank beneath the fuselage. It also meant a long climb up to the cockpit as the canopy was more than 12 ft above the ground the same height as the tip of a static MiG-17s tail! Two pylons could be attached below each outer wing (the undercarriage retracted inwards into the inboard wing space) and the outer pylons were usually used in combat for one or two AN/ALQ-87 electronic countermeasures pods or an AIM-9B Sidewinder. The inboard wing sections contained engine air intakes, uniquely configured with inward-slanting lips.

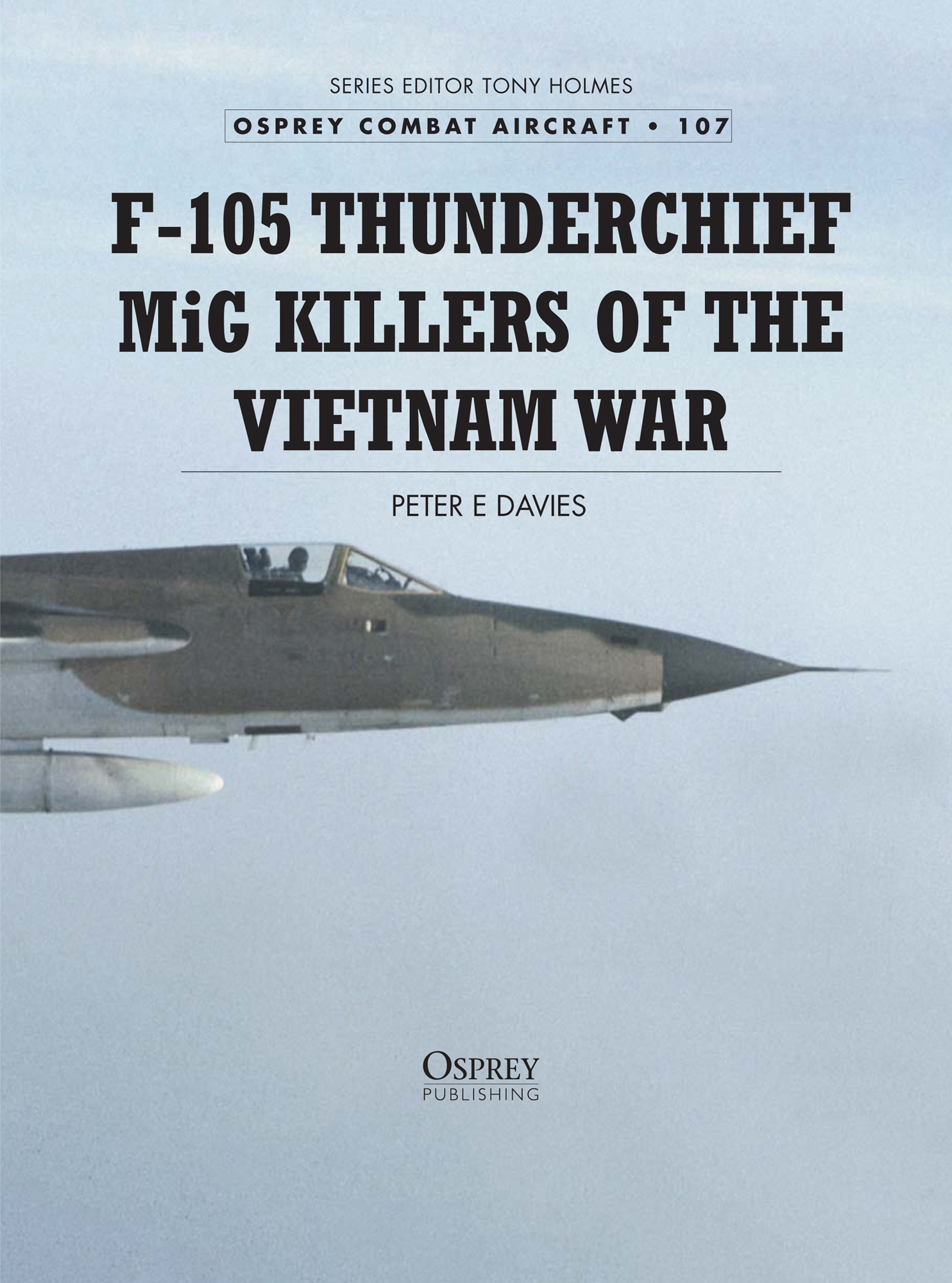

The 4th TFW introduced both the F-105B and F-105D to frontline service. In August 1965 it joined the 18th and 23rd TFWs and 41st AD in deploying Thunderchiefs temporarily to Takhli and Korat, in Thailand. Many of the 4th TFWs 334th TFS F-105s had been camouflaged by then, retaining blue fin bands with white stars, but 61-0105, later the mount of MiG killer Col Bob Scott, was still silver. The limited MiG activity at that time obviated the carriage of AIM-9B missiles (USAF)

Flight controls included ailerons, which operated with five-section spoilers above each wing for roll control at subsonic speeds. At higher speeds the spoilers provided all the roll control. Fowler training-edge flaps were used for takeoff and landing, and for additional lift during manoeuvring flight or, used individually, to assist with roll control. The one-piece horizontal tail was mounted low to avoid wing turbulence and the vertical fin had a rudder operated, like the other control systems, by hydraulic power from three separate systems.

For its original nuclear strike mission no protection was required for these systems, so their supply lines were run virtually parallel in the aircrafts lower fuselage. In combat this would result in many losses when hydraulic lines were hit, so another, physically separated, back-up system was added later. A Republic-designed pilot recovery system, modifying the flying controls to prevent their loss after hydraulic damage, was demonstrated at Takhli Royal Thai Air Force Base (RTAFB) in April 1967 and gradually retrofitted to all surviving F-105s.

F-105D

Weapons delivery avionics in the noses of the 75 production F-105Bs, delivered to the 4th TFW from June 1959, consisted of an MA-8 fire-control system using an E-50 sighting system (in conjunction with an E-34 radar ranging system) and an E-30 toss bombing computer. By the time the B-model entered frontline service the USAFs attention was focused on the all-weather F-105D using the R-14 North American Search and Ranging Radar System (NASARR). A 15-inch nose extension housed the R-14A radar scanner in a larger radome, replacing the E-34. Its Doppler inertial capability gave the pilot constantly updated information on his location, and it became a vital, if somewhat temperamental, navigational aid in poor visibility.