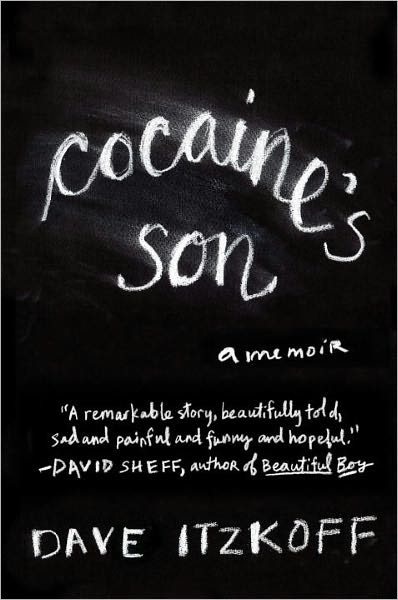

ALSO BY DAVE ITZKOFF

Lads: A Memoir of Manhood

While all of the incidents in Cocaines Son are real, certain dialogue has been reconstructed, and some of the names and personal characteristics of the individuals have been changed. Any resulting resemblance to persons living or dead is entirely coincidental and unintentional.

Copyright 2011 by Dave Itzkoff

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Villard Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

V ILLARD B OOKS and V ILLARD & V C IRCLED Design are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

This work is based on an article originally published in New York magazine on July 24, 2005.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Ice Nine Publishing Company for permission to reprint an excerpt from the lyrics to Duprees Diamond Blues by Robert Hunter, copyright Ice Nine Publishing Company. Used with permission of Ice Nine Publishing Company.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Itzkoff, Dave.

Cocaines son: a memoir / Dave Itzkoff.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-345-52439-3

1. Itzkoff, Dave. 2. Cocaine abuseUnited States. 3. Children of drug addictsUnited StatesBiography. 4. Drug addictsFamily relationshipsUnited States. 5. Fathers and sonsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

HV5810.I89 2011

362.2984092dc22 2010040501

[B]

www.villard.com

Jacket design and illustration: Lynn Buckley

v3.1

For my mother,

who kept us together

When I was just a little young boy

Papa said, Son, youll never get far

Ill tell you the reason if you want to know

Cause child of mine, there isnt really very far to go

ROBERT HUNTER

Contents

He was such an elusive and transient figure that for the first eight years of my life I seem to have believed my father was the product of my imagination. The adult world that I traveled through was populated almost exclusively by women: there were the teachers who trained me on the multiplication tables, the state capitals, and the three branches of government; their aides and assistants; the babysitters, nannies, and housecleaners; the plastic-gloved, hairnetted cafeteria workers who called me Pepito as they ladled out my hot lunches; the school nurse who schemed to deplete me of my saliva with her tasteless wooden tongue depressors; and a jumpsuit-clad handywoman named Celie who spent fruitless hours wading through the school trash to find the loose tooth I threw away, fearing its escape from my mouth meant I was falling apart. There was my sister, who came into existence two years after me; a pair of fragile but living grandmothers, sundry aunts, great-aunts, and cousins. And there was Mom, who sat above them all on this pyramidal structure of progesterone. But there was only one Dad, or so I was told.

It required the combined energies of these many women to discharge the duties normally provided to me by the indefatigable and infinitely resourceful Mom; each had her specialized skills and knowledge, but Mom equaled, encompassed, and surpassed them all. By day, she was not only the Chooser of Clothes, the Maker of Breakfast and the Conveyor to and from School, the Holder of Hands and the Kisser of Cuts and Bruises. She was the Giver of Language, who provided names for the distinctive vagrants who wandered our blockRudolph, with his bright red nose, and Froggy, whose raspy voice carried all the way up from the gutter to our twenty-fifth-story apartment on East Fortieth Street, with what was then an unobstructed view of the East Riverand the Tutor of Numbers, who showed me how the digits of Manhattans streets grew bigger from south to north and from east to west. She taught me that the person whom others called Maddy but whom I knew as Mom were one and the same, and she reminded me that there was another person named Gerry whom I knew as Dad, and that Mom and Dad each had a mom and a dad, too.

By night, she tirelessly rubbed her cool, foul-smelling jellies into my chest when it was filled with phlegm, operated the dials of a mysterious hissing device called the vaporizer, and massaged my feet when the pain from their bones, growing and stretching without my consent, caused me to cry. At dawn, she rose again to implore me not to be frightened by the apocalyptic rumblings of the newspaper trucks roaring forth to make their morning deliveries, backfiring like pistols as they went.

She was my co-conspirator when I sought extra sick days to stay home and watch game shows; she was my chief defender when, as she observed me on my first attempt to purchase my own food at McDonalds, I was pushed out of line by a grown-up female customer. (I told her she was very rude, my mother explained, and for a time I believed this was the most devastating thing a person could be called.) And when she did not feel like dealing with the world, she was my date to a thousand matinees, to movies for which we would always arrive late and then stay in our seats and watch a second time so we could see them in their entirety. Many years passed before I learned that a movie could be watched just once at a theater.

All she asked in return was that I abide, to the letter, by a byzantine system of laws, regulations, and taboos known only to her and forever in flux. Dont play Spider-Man on the weblike netting that extends over the side of our terrace and into the inviting blue sky. Dont leave the dinner table until youve taken five more bites of your foodso determined because I was five years old, and the following year the penalty would go up to six bites. Hand, hand, fingers, thumb! she would call out when we approached the edge of the sidewalk, requesting that we lock digits before she escorted me across the street. Sometimes she would stand with me at a distance from the curb, watching the cars whiz by as the traffic sign changed from WALK to DONT WALK and back. And sometimes, when the sign would blink its final DONT WALK warning, she would get an excited gleam in her eye and clutch my tiny fingers forcefully and exclaim Lets go! and we would race off into the intersection, always making it to the other side just in time.

There was something melancholy about her rules, their preoccupation with the manifold ways that I could be injured and their foreboding certainty that I would be lost the moment she took her eyes off me or a situation arose that she hadnt prepared me for. Even her rules of thumb for shopping at the neighborhood supermarket were a little sad. Dont ever get attached to anything here, she would say. The minute you start liking it, they replace it with something else.

When she really wanted to feel sad, she turned to the hi-fi we kept in our living room. Digging deep into the milk crates she used to house the family record collection, she flipped past the cheerful Sesame Street soundtracks she had accumulated for me and my sister, and a well-worn copy of Free to Be You and Me that promised a new country of green fields and shining seas; past the psychedelic copy of Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band, with its construction-paper insert of a fake mustache and epaulets that I was not allowed to cut into even though the page clearly said CUT HERE ; past the Bette Midler albums and the cast recording of