Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Max, who opened my eyes

The creative adult is the child who survived.

provenance unknown

his mother called him WILD THING!

and Max said ILL EAT YOU UP!

so he was sent to bed without eating anything.

That very night in Maxs room a forest grew

and grew

and grew until his ceiling hung with vines

and the walls became the world all around.

Maurice Sendak, Where the Wild Things Are

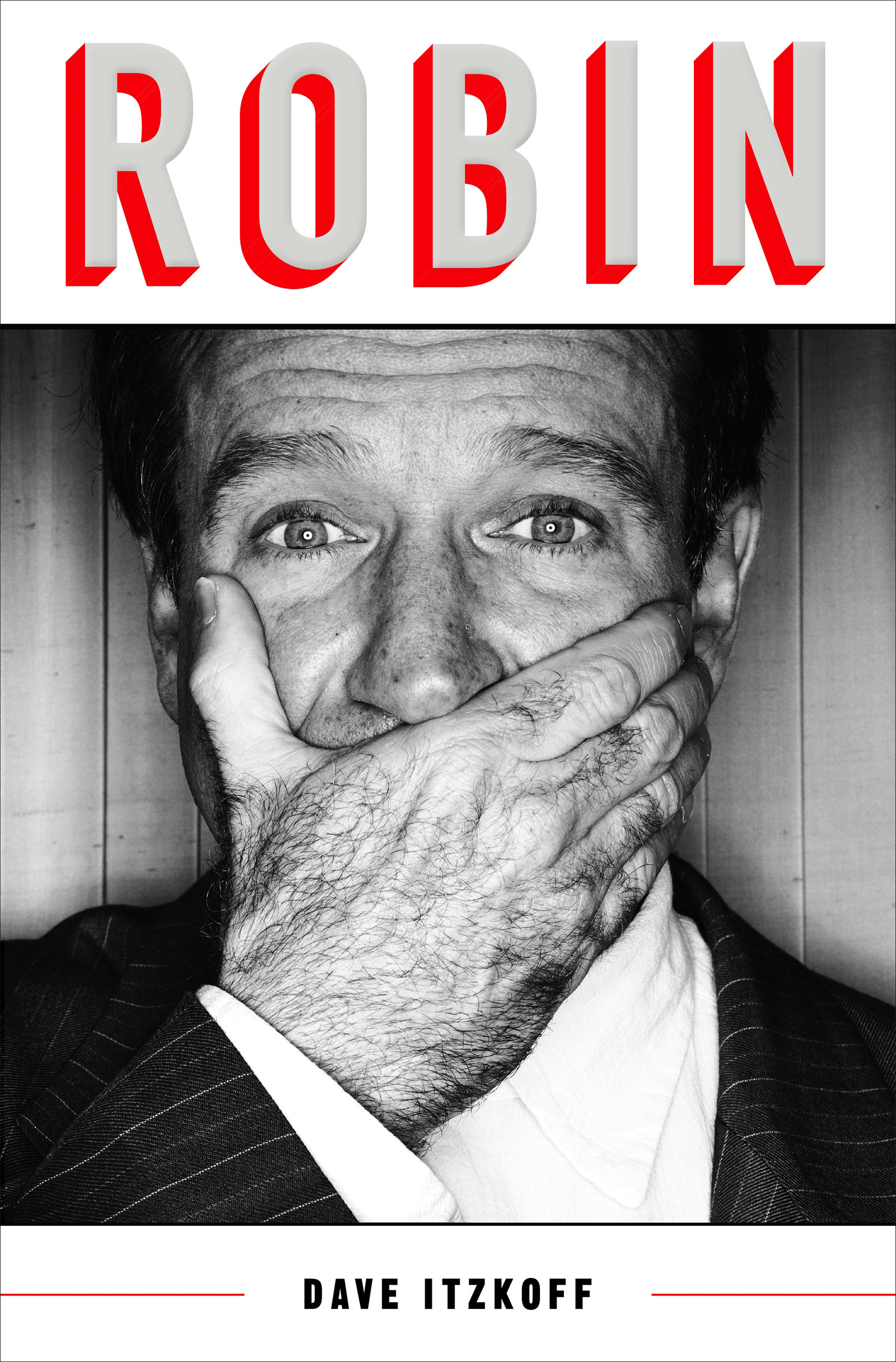

It is the late summer of 1977, and no one in the Great American Music Hall feels like laughing anymore. For hours now, this old, ornate San Francisco theater, which even its admirers have been known to compare to a Barbary Coast whorehouse, has been filling with cigarette smoke. The fetid air has been baking under the lights supplied by a camera crew. The crowd, some six hundred locals dressed in leisure suits and floral prints, are gathered around oak tables, at balconies, and beneath electric chandeliers. They have been sitting here all evening, lured by the promise of free entertainment and the spectacle of a television taping. These are culturally adventurous people in a freethinking city that has lately exploded with comic talent; theyve seen and heard a lot of stand-up already, over the years and on this particular bill, packed with performers whom some of them recognize from the nearby clubs. But the electricity at the top of the show has dissipated as the sweltering night has dragged on. No one has been permitted to leave their seats, not even to go to the bathroom; the atmosphere has gone from stuffy to insufferable in this vast and windowless auditorium. Its hard to imagine a room less receptive to another stand-up comedy act.

Onto the stage strides a handsome, compact man of twenty-six, unfazed by either the steamy temperature or the irritable audience. Dressed in a brown suit, he is a bizarre sight against the gold velvet curtain of the music hall; a battered white T-shirt is visible beneath his suit jacket, its collar barely holding back a generous tuft of chest hair similar to the shaggy patches spreading up his arms and over his hands. He wears an uncomfortable-looking Russian fur hat on his head, and he is dabbed with sweat as a wide, earnest smile unfurls across his face. To anyone watching, he might as well be Russian, a suspicion seemingly confirmed when he speaks for the first time, over the diminishing applause, and says to the audience in a heavy accent, Thank you for the clap, thank you very much. A roar of laughter erupts from the still-puzzled crowd. The comedians act has not even started, and he already has them in his hands.

Over the span of his set, this young man, Robin Williams, will transform himself into any number of characters: in one moment, he is a fidgety, eager-to-please Soviet stand-up comic; the next, a stoned-out Superman, flying backward and upside-down while under the influence of drugs; in still another, the contorted Quasimodo, as portrayed by Charles Laughton in The Hunchback of Notre Dame . He pauses briefly to talk in his natural speaking voiceits cadence so oddly formal that it sounds like he is playing another roleso he can introduce a mid-act commercial in which he is Jacques Cousteau. Peeling off his coat to expose a pair of well-worn rainbow suspenders, Robin is soaked in his own perspiration by the end of his four-minute presentation. Like the needy alter ego he adopted at the start of the routine, he just wants this audience to like him so badly, and he will assume as many identities as it takes until he has achieved this goal. It is a mission he has certainly accomplished by the end of his act, when every member of that exhausted audience is standing on his or her feet, clapping, whistling, and cheering for more. Many of them ask themselves the same question that millions of TV viewers will wonder when this strange, silly, sweaty mans performance is broadcast a few weeks later: Who was he?

No one knows quite how to describe what they have just seen, and the precise words will elude them for months to come. Sure, it was a comedy routine, but the performer didnt tell identifiable jokes with setups and punch lines. He wasnt a monologist or a put-down man, an impressionist or a close observer of quotidian detail. He was more like an illusionist, and his magic trick was making you see what he wanted you to seethe act and not the artist delivering it. Behind all the artifice, all the accents and characters, all the blurs of motion and flashes of energy, there was just a lone man facing the crowd, who decided which levers to pull and which buttons to press, which voices and facades to put on, how much to reveal and how much to keep hidden.

But who was he? Except for that one stray moment when he had spoken a few tentative words in his surprisingly stately voice and then metamorphosed into a French undersea explorer, Robin had never let the audience see his true self. Some part of him would be present in every role and stand-up set he would play over the next thirty-five years, but in their totality these things did not add up to him. The real Robin was a modest, almost inconspicuous man, who never fully believed he was worthy of the monumental fame, adulation, and accomplishments he would achieve. He shared the authentic person at his core with considerable reluctance, but he also felt obliged to give a sliver of himself to anyone he encountered even fleetingly. It wounded him deeply to think that he had denied a memorable Robin Williams experience to anyone who wanted it, yet the people who spent years by his side were left to feel that he had kept some fundamental part of himself concealed, even from them.

Everyone felt as if they knew him, even if they did not always admire the work he did. Millions of people loved him for his generosity of spirit, his quickness of mind, and the hopefulness he inspired. Some lost their affection for him in later years, as the quality of his work declined, even as they held out hope that hed find the thingthe project, the character, the sparkthat had made him great before, as great as he was when he first burst into the cultural consciousness. And when he was gone, we all wished wed had him just a little bit longer.

The house, on the northeast corner of Opdyke Road and Woodward Avenue, was unlike any other. The giant old mansion, nearly seventy years old, stood lovely and lopsided in its asymmetrical design, with its roofs and lofts of varying heights and chimneys that reached into the sky. Here in Bloomfield Hills, a wealthy northern suburb of Detroit where top executives of the automobile industry spent their evenings and weekends in rustic comfort with their wives, children, and servants, the unusual dwelling was more home than a family needed. It sat on a country estate that spanned some thirty acres of former farmland, with a gatehouse, gardens, barns, and a spacious garage that could hold more than two dozen cars. It even had its own name, Stonycroft, a harsh and daunting moniker for a tranquil, out-of-the-way setting. There were few neighbors for miles around and no distractions to disturb its residents from their serenity, aside from the occasional slicing at golf balls that could be heard from a nearby country club. More often, the chilly residence echoed with its own emptiness while its current tenants left many of its forty rooms mostly unoccupied, unheated, and unused. But on its highest floor, spanning the vast width of the house, was an attic. And in the attic there was a boy.