It is almost impossible, by todays standards of celebrity, to comprehend the level of fame that Boris Pasternak engendered in Russia from the 1920s onwards. Pasternak may be most famous in the West for writing the Nobel Prize-winning love story Doctor Zhivago, yet in Russia he is primarily recognised, and still hugely feted, as a poet. Born in 1890, his reputation escalated during his early thirties; soon he was filling large auditoriums with young students, revolutionaries and artists who gathered to hear recitals of his poems. If he paused for effect or for a momentary memory lapse, the entire crowd continued to roar the next line of his verse in unison back at him, just as they do at pop concerts today.

There was in Russia a very real contact between the poet, and the public, greater than anywhere else in Europe, Boriss sister, Lydia, wrote of this time; certainly far greater than is ever imaginable in England. Books of poetry were published in enormous editions and were sold out within a few days of publication. Posters were stuck up all over the town announcing poets gatherings and everyone interested in poetry (and who in Russia did not belong to this category?) flocked to the lecture room or forum to hear his favourite poet. The writer had immense influence in Russian society. In a time of unrest, with an absence of credible politicians, the public looked to its writers. The influence of literary journals was prodigious; they were powerful vehicles for political debate. Boris Pasternak was not only a popular poet hailed for his courage and sincerity. He was revered by a nation for his fearless voice.

From his early years Pasternak longed to write a great novel. He told his father, Leonid, in 1934: Nothing I have written so far is of any significance. Hurriedly I am trying to transform myself into a writer of a Dickensian kind, and later if I have enough strength to do it into a poet in the manner of Pushkin. Do not imagine that I dream of comparing myself with them! I am naming them simply to give you an idea of my inner change. Pasternak dismissed his poetry as too easy to write. He had enjoyed unexpected, precocious success with his first published volume of poetry, Above the Barriers, in 1917. This became one of the most influential collections ever published in the Russian language. Critics praised the books biographical and historical material, marvelling at the contrasting lyrical and epic qualities. A. Manfred, writing in Kniga I revolyutsiya, observed a new expressive clarity and of the authors prospects of growing into the revolution. Pasternaks second collection of twenty-two poems, My Sister, Life, published in 1922, received unprecedented literary acclaim. The exultant mood of the collection delighted readers as it conveyed the elation and optimism of the summer of 1917. Pasternak wrote that the February Revolution had happened as if by mistake and everyone suddenly felt free. This was Boriss most celebrated book of poems, observed his sister Lydia. The more sophisticated younger generation of literary Russians went wild over the book. They considered that he wrote the finest love poetry, in thrall to his intimate imagery. After reading My Sister, Life, the poet Osip Mandelstam declared: To read Pasternaks verse is to clear your throat, to fortify your breathing, to fill your lungs: surely such poetry could provide a cure for tuberculosis. No poetry is more healthful at the present moment! It is koumiss [mares milk] after evaporated milk.

My brothers poems are without exception strictly rhythmical and written mostly in classical metre, Lydia wrote later. Pasternak, like Mayakovsky, the most revolutionary of Russian poets, has never in his life written a single line of unrhythmic poetry, and this is not because of pedantic adherence to obsolete classical rules, but because instinctive feeling for rhythm and harmony were inborn qualities of his genius, and he simply could not write differently. In a poem written shortly after My Sister, Life was published, Boris bids farewell to poetry: I will say so long to verse, my mania I have an appointment with you in a novel. Still though, he glorified prose-writing as being too difficult. Yet the two modes of writing actually shared an intrinsic relationship in his work, regardless of the genre. In his autobiography Safe Conduct, published in 1931, a mannered account of his early life, travels and personal relationships, he wrote: We drag everyday things into prose for the sake of poetry. We draw prose into poetry for the sake of music. This, then, I called art, in the widest sense of the word.

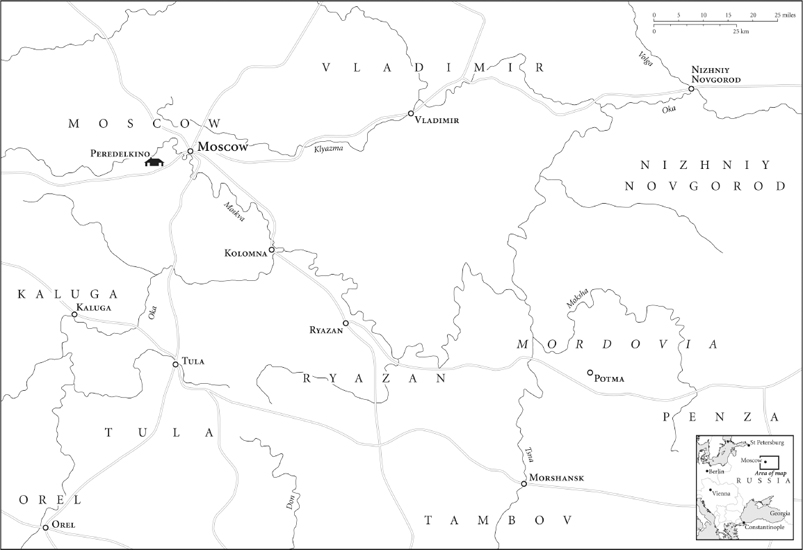

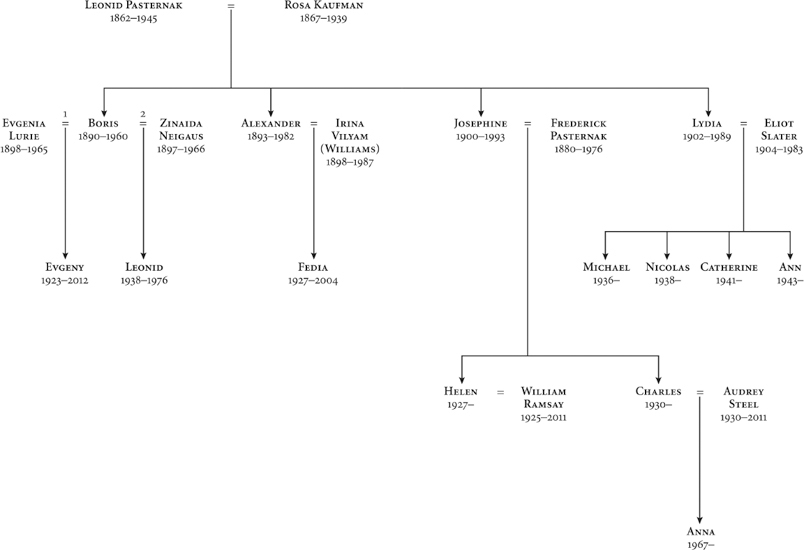

It was in 1935 that Pasternak first spoke of his intent to fulfil his artistic potential by writing an epic Russian novel. And it was to my grandmother, his younger sister, Josephine Pasternak, that he first confided his ideas at their last meeting at Friedrichstrasse station in Berlin. Boris told Josephine that the seeds of a book were germinating in his mind; an iconic, enduring love story set in the period between the Russian Revolution and the Second World War.

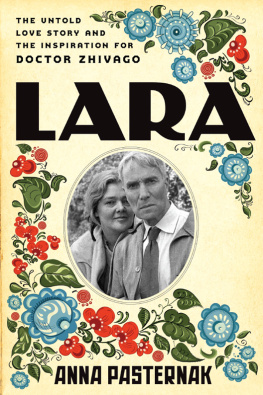

Doctor Zhivago is based on Boriss relationship with the love of his life, Olga Vsevolodovna Ivinskaya, who was to become the muse for Lara, the novels spirited heroine. Central to the novel is the passionate love affair shared by Yury Zhivago, a doctor and poet (a nod to the writer Anton Chekhov, who was also a doctor) and Lara Guichard, the heroine, who becomes a nurse. Their love is tormented as Yury, like Boris, is married. Yurys diligent wife, Tonya, is based on Boriss second wife, Zinaida Neigaus. Yury Zhivago is a semi-autobiographical hero; this is the book of a survivor.

Doctor Zhivago has sold in its millions yet the true love story behind it has never been fully explored before. The role of Olga Ivinskaya in Boriss life has been consistently repressed both by the Pasternak family and Boriss biographers. Olga has regularly been belittled and dismissed as an adventurous, a temptress, a woman on the make, a bit part in the history of the man and his book. When Pasternak started writing the novel, he had not yet met Olga. Laras teenage trauma of being seduced by the much older Victor Komarovsky is a direct echo of Zinaidas experiences with her sexually predatory uncle. However, as soon as Boris met and fell in love with Olga, his Lara changed and flowered to completely embody her.