ADVANCE PRAISE FOR PAOLO MANCOSUS

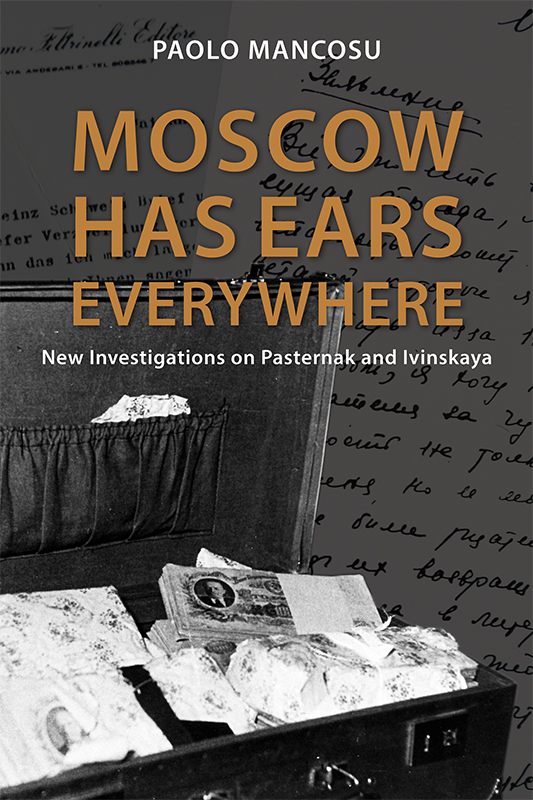

Moscow Has Ears Everywhere: New Investigations on Pasternak and Ivinskaya

Paolo Mancosus richly documented and profoundly moving account of some of the most dramatic episodes in the cultural life of the Cold War period is a major contribution to Pasternak scholarship and Russian studies.

Lazar Fleishman, Stanford University

Paolo Mancosus new book is a treat for the specialist and the general reader. Mancosu has unearthed an enormous amount of new documentary evidence that sheds a completely new light on a story we thought we knew well: Pasternaks persecution following the Nobel Prize award, the arrests of Olga Ivinskaya and Irina Emelianova, and their subsequent release. Mancosu unveils the surprising twists of the story and weaves a rich tapestry describing the political, literary, and private relations among the protagonists. Most important, he gives us insights into their inner livesthe lives of outstanding and ordinary people enmeshed in the cruel hostility of the Cold War. It is a splendid achievement.

Anna Sergeeva-Klyatis, Moscow State University

Professor Mancosus book investigates the postNobel Prize events in Pasternaks life and the repercussions of his confrontation with Soviet power on his beloved Olga Ivinskaya and her daughter Irina Emelianova. It represents a quantum leap in our understanding of those events, both on account of the impressive number of unknown archival sources Mancosu brought to light as well as for the thorough and careful interpretation of those tragic events. Mancosus first-rate study is a must read for anyone interested in the relationship between literature and politics during the Cold War.

Fedor Poljakov, University of Vienna

With its eminent scholars and world-renowned library and archives, the Hoover Institution seeks to improve the human condition by advancing ideas that promote economic opportunity and prosperity, while securing and safeguarding peace for America and all mankind. The views expressed in its publications are entirely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, officers, or Board of Overseers of the Hoover Institution.

www.hoover.org

Hoover Institution Press Publication No. 698

Hoover Institution at Leland Stanford Junior University,

Stanford, California 94305-6003

Copyright 2019 by Paolo Mancosu

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher and copyright holders.

Efforts have been made to locate the original sources, determine the current rights holders, and, if needed, obtain reproduction permissions. On verification of any such claims to rights in the articles reproduced in this book, any required corrections or clarifications will be made in subsequent printings/editions.

First printing 2019

252423222120197654321

Manufactured in the United States of America

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum Requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN: 978-0-8179-2244-3 (cloth. : alk. paper)

ISBN: 978-0-8179-2246-7 (epub)

ISBN: 978-0-8179-2247-4 (mobi)

ISBN: 978-0-8179-2248-1 (PDF)

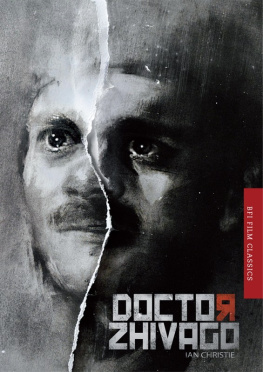

Preface

Doctor Zhivago has been slow in disclosing its mysteries. Only recently have the archives begun to reveal the full complexity of the Zhivago affair. The documents of the Central Committee of the CPSU (Le dossier 1994; Afiani and Tomilina 2001), the Zhivago files recently declassified by the CIA (www.foia.cia.gov/collection/doctor-zhivago; Finn and Couve 2014; Mancosu 2016), and vast holdings in the Feltrinelli archives (Feltrinelli 1999; Mancosu 2013), to name just a few of the major troves of new information, are telling a story that defies belief.

Of all the events related to the Zhivago affair, one stands out as having so far resisted closer scrutiny. I am referring to the events that followed Pasternaks death and that led to the arrests of Pasternaks lover and literary assistant, Olga Ivinskaya, and her daughter, Irina Emelianova. This neglect is especially surprising in light of the wide publicity and international visibility generated by the arrests and sentences of Olga and Irina.

The present book consists of three chapters and a documentary appendix, which stem from three long articles I recently published on the Ivinskaya case. It is not an attempt to tell the story of Boris Pasternak and Olga Ivinskaya, a story already recounted first by Olga Ivinskaya herself (Ivinskaya 1978), then by her daughter, Irina Emelianova (Emelianova 2002), and by more recent authors. Rather, my goal is to present hitherto unknown material that enriches, complements, and at times debunks previous accounts. Given the novelty of the material I am presenting, the book will consist of three chapters (chapters 1 to 3) that analyze and put the new documents in context, followed by a large selection of the documents in the appendix. In the original articles from which the chapters originate (Mancosu and Borokhov 2017; Mancosu 2018a; Mancosu 2018b), the documents were also presented in the original language. Here the documents will be presented only in English translation. Other changes have been made to the original articles to eliminate repetition and ensure a smooth transition between chapters. In addition, I have updated the bibliography, and appropriately modified the narrative, to include references to articles that have appeared since my original articles were written. From the point of view of content, the major change is reflected in section 2.2, which improves the account given in the corresponding section in Mancosu 2018a. A little asymmetry has been preserved in the presentation of the documents, in that the first twenty letters, from 1956 to May 1960, are each accompanied by a commentary that supplements what is said in the main text. This is because those letters often refer to events not treated in the main text and thus require additional context. Also documents 41 and 46 have an individual commentary. By contrast, the context of the remaining letters, dating from June to September 1960, is sufficiently clarified by what is said in the main text. But before I move to a more detailed description of the chapters and the documents, let me give a quick biographical sketch of Olga Ivinskaya.

Olga Vsevolodovna Ivinskaya was born on June 16, 1912, in Tambov. In 1915, her family moved to Moscow. She studied at the Editorial Workers Institute in Moscow, from which she graduated in 1936. In that same year, she married Ivan Emelianov, with whom she had a daughter, Irina Emelianova, born in 1939. In the same year, Ivan committed suicide by hanging himself. In 1941 Olga married Aleksandr Vinogradov. They had a son, Dmitri, born in 1942, who will appear in our story under Mitia. Vinogradov died after an illness in 1945. Olga worked as a literary editor, and she met Pasternak in 1946 in the editorial offices of