Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2016 by Dawn E. Bakken

All rights reserved

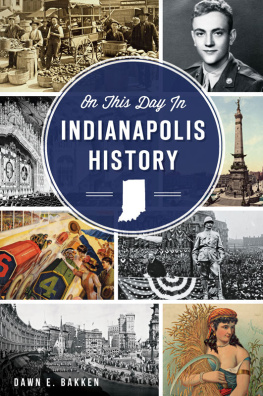

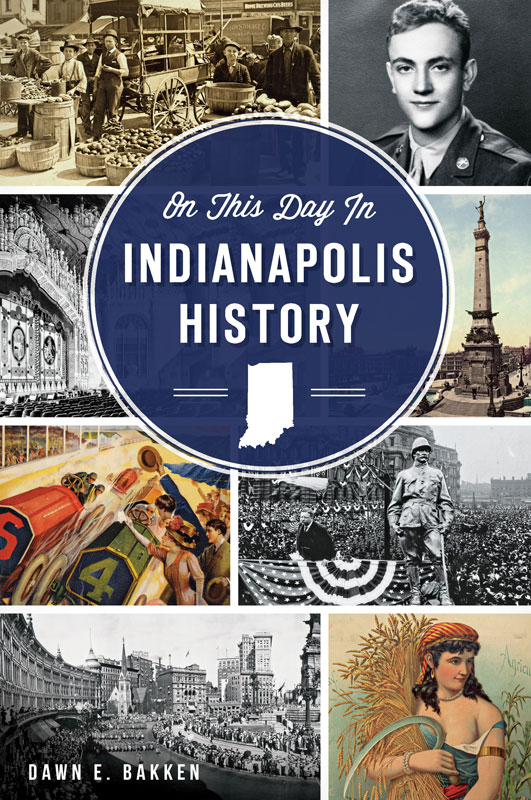

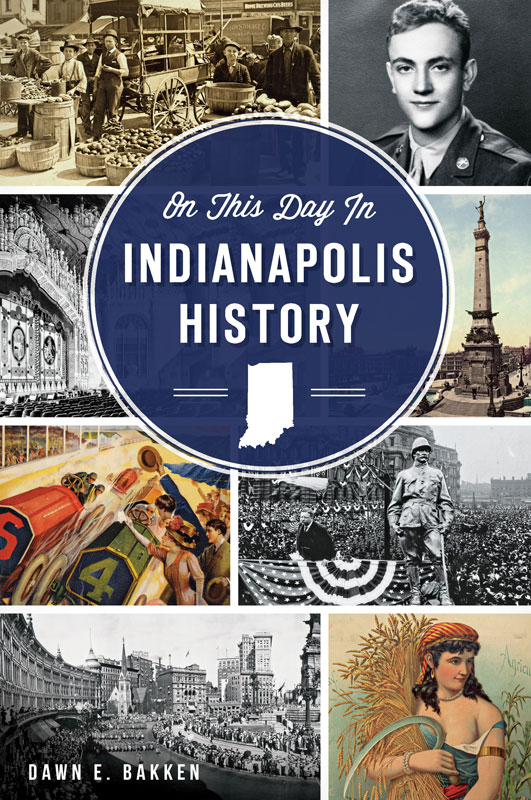

Front cover: City Market, 1908. Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division (LOC); Kurt Vonnegut Jr. Courtesy Vonnegut Family Archives; Soldiers and Sailors Monument, 1904. Courtesy LOC; World War I Farewell Parade, 1918. Courtesy LOC; Indiana State Fair Poster, 1886. Courtesy LOC.

First published 2016

e-book edition 2016

ISBN 978.1.62585.282.3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015954745

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.757.2

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to my parents, Darrell Bakken and Ruth Partridge Bakken, for teaching me a love of history and a love of reading. Both have led me to the job I am thankful to hold. Thanks to all of my colleaguesfaculty and graduate studentsat the Indiana Magazine of History, who have taught me so much about the process of researching, writing and revising history that is pleasurable to read, interesting and academically sound.

The new generation of technically proficient librarians has saved me countless hours of work. Thanks especially to the wonderful people at the Digital Library Program at Indiana UniversityBloomington who digitized the Indiana Magazine of History, to the librarians at the Indiana State Library who have worked with the Library of Congress to digitize historic newspapers from all over the state and to the librarians at Indiana UniversityPurdue University Indianapolis for their digital collections relating to the history of Indianapolis.

Finally, thanks to Leslie Olsen of the Childrens Museum of Indianapolis and to Julia Whitehead of the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library and members of the Vonnegut family for their generosity in providing two of my cover illustrations.

INTRODUCTION

In the summer of 1965, just before I entered first grade, my family moved to Indianapolis. We moved into a ranch-style house on the citys west side, and if the wind was coming in the right direction on race day, you could listen to the Indianapolis 500 on the radio from our driveway and hear the sound of the cars in the air. I attended Indianapolis Public Schools until we moved a little farther weststill within the bounds of the city, thanks to Unigovwhere I attended Ben Davis High School. Many of my memories of Indianapolis are from the city of the mid-1960s to late 1970s: Pacers games when the team was still in the ABA; the Indianapolis Indians at Bush Stadium; fireworks downtown on the Fourth of July; the Indianapolis 500 (with my father, from high seats just into the first turn); a bus trip downtown with my mother every December for a days shopping (and lunch at the Tea Room) at L.S. Ayres. The city today is vastly different from the one in which I grew up. But then Indianapolis, in its almost-two-hundred-year history, has undergone much greater changes than those of the last few decades.

Indianapolis was a town invented by the state legislature, and it grew slowly from its frontier origins. Until the 1850s, growth was held back by inadequate roads, a failed canal system and an unnavigable river. Railroads began to transform Indianapolis; the technological progress of postCivil War America furthered the citys growth. By the turn of the twentieth century, Indianapolis was a bustling city that was home to three of the nations most popular authors and to more than sixty factories manufacturing that new sensation, the automobile.

The city, like others in the Midwest, saw urban decay threaten in the 1960s and 1970s. Renewal came about from the work of mayors and local business leaders, members of neighborhood associations, historic preservationists and the owners, promoters and fans of a wide variety of sports. Indianapolis, when it was known for little else, was famous for the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and the Indy 500. By the end of the twentieth century, it was home to major league NFL and NBA teams, its longtime professional baseball team had a wonderful new downtown home, it had become a perennial host for Olympic trials and NCAA tournaments and the Speedway was hosting NASCAR and Formula One races.

The stories in this book are not presented in chronological order. I begin in 1970 and end in 1823. I have written about men and women who played major roles in the life of the city and the state (and sometimes the nation) and people whose names have been lost to history. You will find entries about a statehouse styled after a Greek temple and a roadhouse where John Dillinger and his gang went to drink. I have inevitably left out people, places and events that will be remarked on by some readers. The content, including errors and omissions, may be attributed solely to the author.

JANUARY

January 1, 1970

In one day, Indianapolis went from the twenty-sixth-largest city in the nation to the eleventh, when it became incorporated with Marion County into the political entity known as Unigov. By the 1960s, the county encompassed Indianapolis and a number of independent cities with their own mayors and councils, local ordinances, schools and police and fire forces. Indianapolis mayor Richard G. Lugar proposed a consolidation intended to streamline government, cut costs, improve efficiency and help revitalize the urban center of Indianapolis. The city would be governed by a city-county council, with an executive branch that oversaw administration of the county, and a city-county court system. Some cities, including Speedway and Beech Grove, retained much of their autonomy; schools remained divided between city and township; and many county offices mandated by the state constitution were retained. Urban planners, inside and outside the state, praised the move as a bold rethinking of city government. Within the city and throughout Indiana, reaction differed widely, but decades later, Unigovs basic structure remains in place.

January 2, 1910

Electric Cars Collide in Dense New Years Fog read the Indianapolis Star headline. An interurban car leaving downtown Indianapolis headed to Martinsville had been struck by a city car carrying residents home. Passengers escaped the wreckage of the smaller car, although the driver later died from injuries. The citys first interurban linefrom Indianapolis to Greenwood to Franklin and backhad begun on January 1, 1900. Three weeks later, the Board of Public Works set the ticket price at six for twenty-five cents, with transfers included. By 1904, so many lines and so many cars were coming into and going out of the city that the interurban companies built the Indianapolis Traction Terminal downtown. By 1910, every city within a 120-mile distance from Indianapolis could be reached via a low-priced ticket on a comfortable electric interurban car. Most lines ran ten to twelve trains per day from early in the morning until late at night, and interurban transportation quickly became a preferred mode of travel within central Indiana. Ten thousand people passed through the Traction Terminal on an average day.

Next page