First published in Great Britain in 2017 by Osprey Publishing, PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK

1385 Broadway, 5th Floor, New York, NY 10018, USA

E-mail:

This electronic edition published in 2017 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Osprey Publishing, part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

2017 James Kinnear and Stephen L. Sewell

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Every attempt has been made by the Publisher to secure the appropriate permissions for material reproduced in this book. If there has been any oversight we will be happy to rectify the situation and written submission should be made to the Publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

James Kinnear and Stephen L. Sewell have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the Authors of this Work.

ISBN: 978-1-7844-2239-4 (HB)

ISBN: 978-1-4728-2051-8 (eBook)

ISBN: 978-1-4728-2052-5 (ePDF)

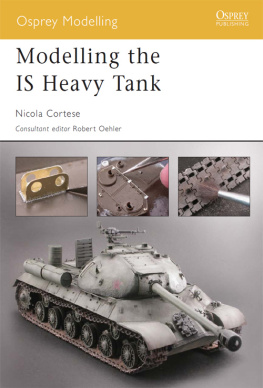

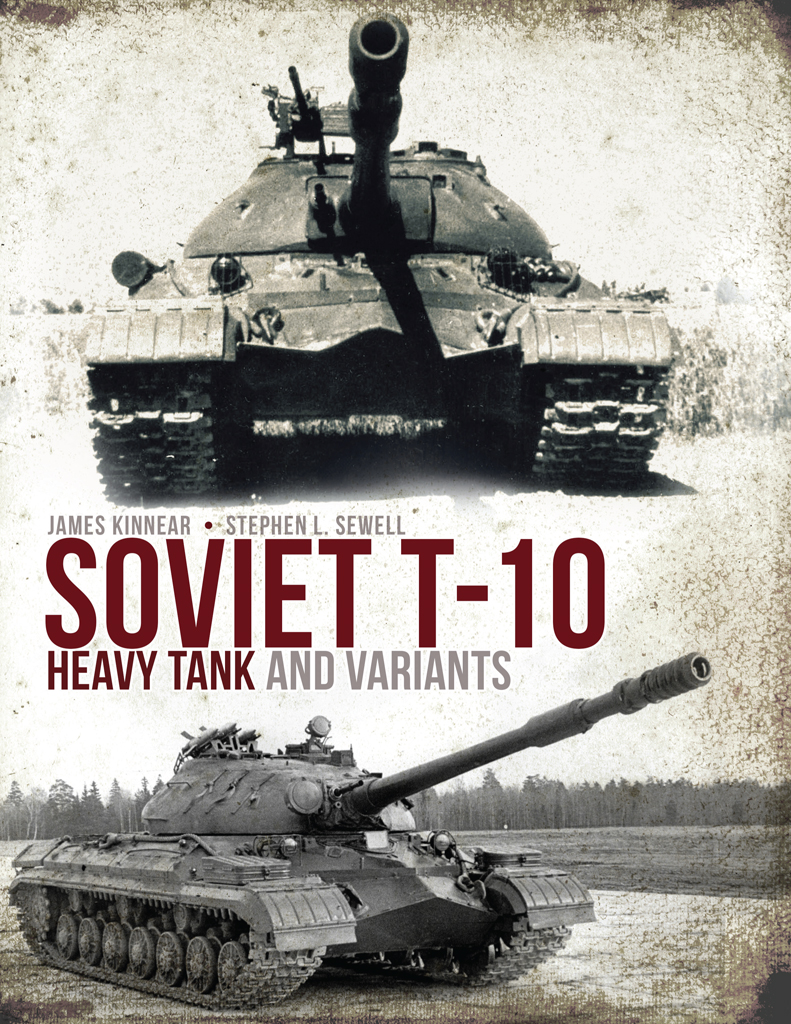

Front cover: Upper, T10M Obiekt-734 (see ).

Back cover, top to bottom: L2 infrared searchlight (see ).

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.ospreypublishing.com. Here you will find our full range of publications, as well as exclusive online content, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters. You can also sign up for Osprey membership, which entitles you to a discount on purchases made through the Osprey site and access to our extensive online image archive.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of many people, primarily located within the Russian Federation and Ukraine, for providing original Soviet and Russian source material and photographs for this book. Source material on the T-10, particularly photographs, proved to be the proverbial hens teeth to find and ultimately extract, but the published results are an accurate recounting of the history of a long-mysterious tank series based on original primary source Russian language material.

In particular, thanks must go to Andrey Aksenov, Aleksandr Koshavtsev, Yuri Pasholok and Igor Zheltov in Russia, Sergei Popsuevich in Ukraine, and Steven Zaloga in the US, all of whom provided what material they had available to ensure completeness of this work. Thanks also go to Sergei Netrebenko and Evgenniy Ivanov for the provision of invaluable original source research material.

The artwork for this book was provided by Andrey Aksenov and the drawings by Aleksandr Koshavtsev.

NOTE ON THE TRANSLATION OF THE RUSSIAN LANGUAGE

The Russian alphabet has more characters than the Latin based English language, while the Russian language is also grammatically complex and subject to varying translation depending on context, gender and time period. Therefore it is not always possible to directly translate Russian terms or names into English. For instance, Iosef Kotin the tank designer has a given name that starts with a Russian letter with no English equivalent, such that he might be called Zhosef, or Iosef (Joseph). Further, Russians are historically formal in addressing each other and use the patronymic (the fathers given name) as the middle name part of a persons formal address. Kotins father was Yakov (Jacob), a name that also starts with a letter not in the English language alphabet. So Kotin becomes Zhosef Yakovlevich Kotin, abbreviated to the awkward English translation Zh. Ya. Kotin. Therefore for ease of reading in English, the authors have simplified the translations, such as in the case of Kotin omitting the patronymic and naming him Iosef Kotin. Similarly, designations such as Obiekt, again with a specific Russian letter in the middle with no English equivalent, have been simplified as Obiekt, and so on.

Further, there are inherent difficulties in consistency when detailing production plants, for which the Russian term is Zavod or Fabrika. The Leningrad Kirov Zavod (LKZ), where heavy tanks from the KV to the T-10 were built, is often referred to colloquially as the Kirovsky Zavod (the Kirov Plant), as all Russians know its location as being in Leningrad, now St Petersburg. Meanwhile, the Chelyabinsk Kirovsky Zavod (ChKZ) in the Urals, which was established after the evacuation of the machine tooling and personnel from the original Kirov Plant in the autumn of 1941, was renamed Chelyabinsk Tankovy Zavod (ChTZ) from 15 May 1958. This is why plant references are often conflated, and often the plant drawings are themselves misleading, as for instance ChKZ stamps were used long after the plant was renamed ChTZ. The ChKZ and ChTZ plants are one and the same, the designation changing only according to the date concerned, and T-10 production spanned the years when the changes were made.

The authors trust this the simplification of translation and terminology for ease of reading in English is acceptable, and no slight is intended by dropping the patronymic from the names of those Russian nationals mentioned in the book.

Osprey Publishing supports the Woodland Trust, the UKs leading woodland conservation charity. Between 2014 and 2018 our donations will be spent on their Centenary Woods project in the UK.

www.ospreypublishing.com

CONTE NTS

I NTRODUCTION

The T-10 was the last series production Soviet heavy tank, the last of the Stalin heavy tank family which began with the IS-85 (IS-1) introduced into service in 1943, followed by the wartime IS-122 (IS-2), and preceded directly by the post-war series production IS-3 and IS-4 heavy tanks, which were both technically advanced but had proved troublesome in service.

When introduced into service in 1953, the enigmatic T-10 represented a return to the classic Soviet heavy tank, with a combat weight of under 50 metric tonnes. The T-10 series was relatively obscure in service, and, as with the IS-4, was not exported outside the Soviet Union. Although considered a major threat to NATO tank forces, continuing as it did the genealogical line started with the IS-3 in 1945 that had been such a shock to Allied forces at the 1945 Allied Victory Parade in Berlin and had prompted major heavy tank development programmes in the US, UK and France, the T-10 also represented the end of an era. The high cost of manufacture and considerable maintenance requirements of the T-10 were well known at the time of its service, while the years under Soviet Premier Khrushchev were difficult for the T-10 as the rocket enthusiast Khrushchev was against all gun tanksand heavy tanks in particular. While he may have been biased towards rocket technology that the Soviet science of the day was unable to deliver in a timely manner, he was right about heavy tanks. The arrival of the T-62 MBT (Main Battle Tank) only a few years after the original T-10, and the imminent service introduction of the T-64 MBT with powerful next generation armament and new ammunition types, made the T-10 and heavy tanks in general effectively redundant. The T-10 tank was gradually withdrawn from service in the 1970s; however, the T-10 series was only officially removed from service by Decree of the President of the Russian Federation in 1997. As such, the T-10 outlived the Soviet state that had created it.