All rights reserved.

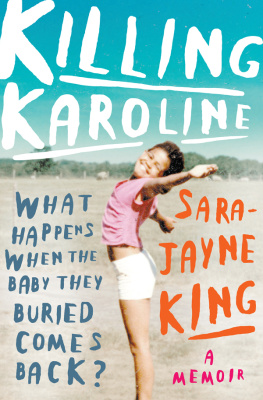

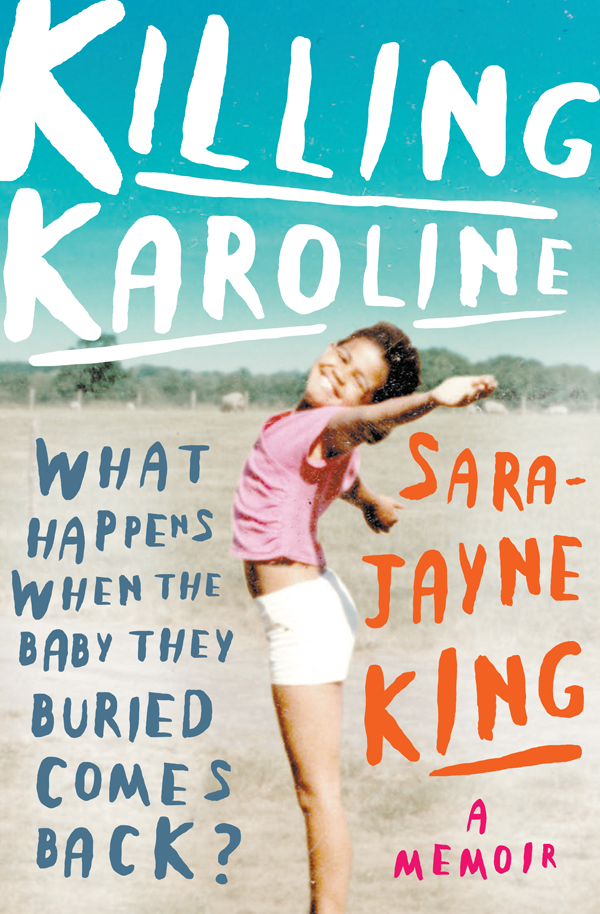

For the battle brave who, despite their wounds, remain unwavering on their journey for self truth.

Cape Town, June 2008

Just dont write a book about it.

He had said it rather weakly, an even feebler attempt at levity in his voice. But the look on his face betrayed him. It was clear he wished it were within his power to stop it whatever it was going any further than it had already. We, all of us, had known that things would never be the same again, but only I seemed prepared for what was happening.

Surely they must have realised that this moment would come one day? Had they never talked about it, about what would happen? Prepared and rehearsed their lines, braced themselves for the return, the resurrection of Karoline? Had he not, over the years, predicted this exact scene, played it over in his mind countless times, as I had?

He continued to stare into his wine glass, as if hoping that the answers would miraculously be found swirling in the remnants of his Shiraz his own vintage or better, that the next two hours of our lives would simply evaporate into time and disappear like so much already had. He would be disappointed. I had been silent, hidden away for so long, but now I had come out of hiding. I had risen from the grave and I had a voice. It wasnt that I had suddenly become brave, but rather that the time had come. A time not determined by me, but by something larger than all of us. There was nothing left to do but this.

There are moments in the short years we are given when that which we may once have considered the riskiest path of all becomes the surest ground on which we can walk. We still see the cracks, feel the tremors of the unsettled earth underfoot, and sense the presence of the fragile and unpredictable and recognise the sense of certainty. The knowledge that this is the path that we must take. And so, with our bootlaces tight, our armour secure, and holding firm to our resolve, we take the first step and even if that on which we walk crumbles to dust, we know , we are sure we are headed in the right direction.

As I stood before him, for the first time in twenty-seven years, I was scared, yes, but mostly angry and, oddly, rather powerful. So what was it that I wanted? Acknowledgement? That age-old antithesis of self-deception? Dont we all just want to be seen? To know that weve been heard, our experiences recognised, the essence of who we are valued and validated? If nothing else, did I not have a right to that at least? And there was really nothing else. But acknowledgement elusive, beautiful, weight-shifting acknowledgement was the stuff of fantasy, because the very reason we had come to be here was the result of a thing conceived in a bed of deception and denial. A refusal, an inability, an unwillingness to see .

So what was it that I wanted? Acceptance? George Orwell once wrote that Happiness can only exist in acceptance. Did that mean my happiness rested on their acceptance of me? I had been unhappy for so damn long, did I dare risk putting something so precious into the hands of those who had already been the cause of so much of my sadness?

What was it that I wanted ? Control perhaps? That was possible. For the first time ever, for just a brief moment, I felt like I held the reins, that I was taking back command. I could ruin him if I wanted, I thought. But I knew I wouldnt, and that angered me even more.

What was it that I wanted? Revenge? There was a time that I thought I did. But what would that revenge be? How? Revenge was a fantasy and one that, in reality, rarely delivered on its promise. And so instead I tried hard to look bored, to manifest my resentment into overt indifference; show him I couldnt have cared less. I wanted the tension to be palpable.

I wandered around the apartment, his apartment musing at the predictability of it all. The expensive artwork, the mood lighting, the cream carpets and white leather sofas that made the place look like a show home. A faade. It was so him . Not that I knew him, but I needed something on which to hang the disdain Id been carrying with me ever since Id walked through the door. I yawned widely, hoping I was managing to convey the appropriate level of boredom and apathy. If Id been braver, Id have lit a cigarette. It was clearly a non-smoking house. I was desperate for a glass of wine, or something stronger, but I hadnt had a drink for close to a year.

Inwardly, I began to seethe, especially when he began to tell me about his plans for landscaping the roof garden, the convenience of being so centrally located, and surely it wasnt appropriate to play music? I was incensed. I sat and thought of how hed welcomed me into the apartment, pulling me into a polite embrace. No, it was all far too presumptuous; who the hell did he think was?

And there it was. Because the irony of it was that this man, into whose life I had entered some twenty-seven years before, this man whom I needed to hate, but also needed to be acknowledged by, was, in a place and a time, my father . Whatever the truth was, it was this man whose name appeared in black and white on my birth certificate. But this man had killed me. This man and the woman who had carried me in her belly had killed me , and they had killed Karoline.

CHAPTER 1

Whats in a name?

I didnt become my parents child in the traditional way. Neither one of them was in the delivery room when I was born on 1 August 1980 at Sandton Clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. Neither had watched me take my first breath or cut the gristly cord attaching my umbilicus to the womb from which I had been expelled. They didnt even give me my first name. Karoline.

Instead, the people I call Mum and Dad became my parents by way of a couple of signatures scrawled on a piece of paper, rubber-stamping my status as their child. Literally, a rubber stamp, administered by a clerk at Reigate County Court in Surrey, England, on 20 January 1981. That was nearly six months after I had been born and four months since they had collected me from the adoption agency in London, where moments before, a woman my biological mother and her husband, the man whose name appeared on my birth certificate, had given me away. At just seven and a half weeks old, they had left me in the arms of strangers and walked away. Because of the colour of my skin.

I was supposed to have been called Emma, after the protagonist in the Jane Austen novel. In the years prior to my ill-fated conception, way before I was born with a large, black question mark over my head and long before I was signed by a magistrate into my adoptive parents lives, that was the name that had been picked out for me by my adoptive father, Malcolm. He had been reading the book while on honeymoon with my adoptive mother, Angela, and had been taken with the name. A smart and opinionated man, he likely had it in mind to raise a similarly intelligent, forthright daughter and was no doubt inspired by Austens leading lady, despite her being described by Austen herself as a character she suspected no one would much like. As it was, the book, which had served as inspiration for the name of the daughter they did not yet have, was left on the beach one day and had been urinated on by a dog. By the time of my birth and adoption some nine years later, my parents had long given up hope of having a daughter and so had bequeathed the name instead to one of their pet goats. So it was that I, when I came to live with them at age seven and a half weeks, came to be known as Sarah. Sarah Jane, perhaps in honour of Austen herself. I disliked the name for years. Incredibly plain, I often thought. Didnt suit me. It was nowhere near unique enough, glamorous enough, exotic enough, me enough. I felt I should have been a Perdita or a Zara, or at the very least a Jennifer. A name, perhaps, that was hard to spell. But my parents were not frivolous people, so it was unlikely I would ever have been bestowed anything quite as colourful.