eBook co-published in 2012 by:

Helion & Company Limited

26 Willow Road

Solihull

West Midlands

B91 1UE

England

Tel. 0121 705 3393

Fax 0121 711 4075

email: info@helion.co.uk

website: www.helion.co.uk

and

30 South Publishers (Pty) Ltd.

16 Ivy Road

Pinetown 3610

South Africa

email: info@30degreessouth.co.za

website: www.30degreessouth.co.za

Copyright Leon Bezuidenhout, 2011

eBook Leon Bezuidenhout 2012

ISBN 978-0-620474-79-5

ISBN 978-1-908916-13-6 (eBook)

Design and origination by 30 South Publishers (Pty) Ltd.

Front cover photo Herman Grobler

Back cover photo Kallie Calitz

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, manipulated in any retrieval system, or transmitted in any mechanical, electronic form or by any other means, without the prior written authority of the publishers except for short extracts in media reviews. Any person who engages in any unauthorized activity in relation to this publication shall be liable to criminal prosecution and claims for civil and criminal damages.

Dedicated as a monument to those in the Namibian bush war without any memorial

the 128 black Namibian Koevoet policemen who died in action or from wounds

*

Kuyofa abuntu rusale izibongo, yizona eziyosala emanxiweni

People will die and their praises remain;

it is these that will be left to mourn for them in their deserted homes

From the praises of Dingane, Zulu king

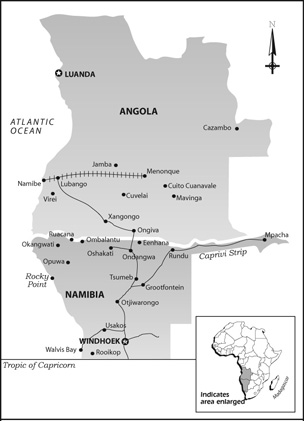

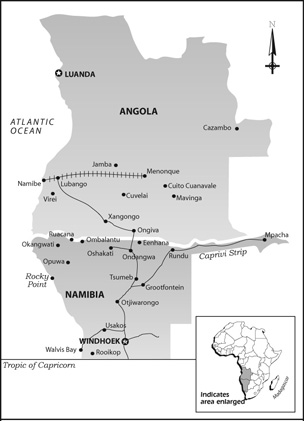

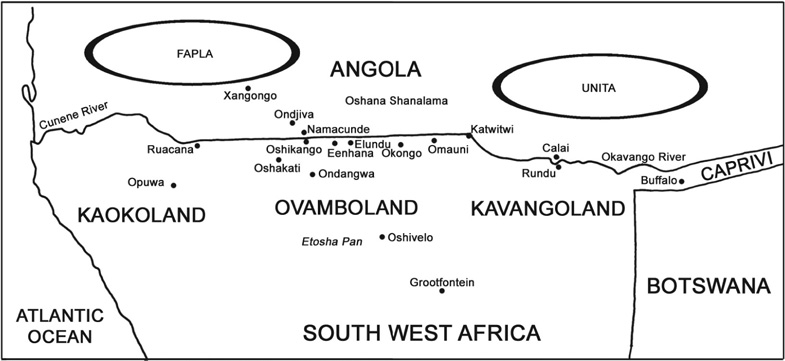

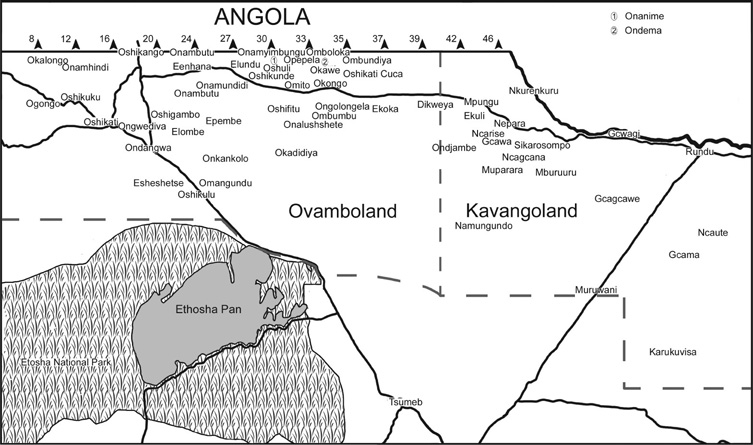

SOUTHERN AFRICA

Contents

The co-author, Leon Bezuidenhout, is grateful to the following:

Francois du Toit, who introduced me to the people at Vingerkraal as well as to the incomparable Sisingi Shorty Kamongo. For sharing a few of his stories. He has many more.

Kallie Calitz, a brave man, for his photographs and input.

Marinda Conradie, for the English translation of the Herman Grobler story, her advice and suggesting the title for this book.

Rustus Mbundu, for his contribution about his involvement at the battle of Opepela.

Sakkie Kaikamas, Casspir driver who shared a story or two.

Jacques Myburgh for allowing us to use his account of 3 April 1989.

Ilse van Staden, for the maps.

Leopold Scholtz, historian, author and journalist, for his foreword and critical perspective.

Alec Wainwright, for his critical reading and advice.

Theo de Jager, for helping solve the bull riddle.

Hendrik Engelbrecht; I would have loved to have met him, but he died while I was tracing him. I should have tried harder.

My wheelchair-bound friend, Sisingi Shorty Kamongo, an exceptional and talented human being, a man among men.

During the past years, a host of personal reminiscences have been published by people who fought in the Border Warsome in book form, others on the Internet. At the highest level former minister of defence, General Magnus Malan, put pen to paper, as did the chief of the defence force in the latter half of the 1980s, General Jannie Geldenhuys. The others are troops, all of them from the South African army, people who tell of the endless patrols, the flies, the heat, the boredom, or of the fear, blood and guts of conventional crossborder operations in Angola.

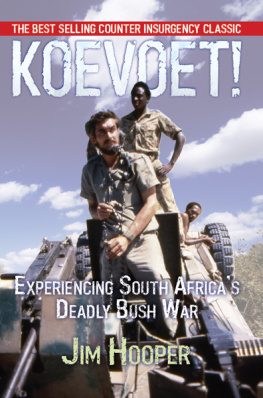

The stories of some SWAPO members have also been recorded. However, there are two important lacunae in this literature. Firstly, there is one unit on the South African side from which not a single member has told his story: the South African Polices special counter-insurgency unit, known as Koevoet. The writer Peter Stiff has, it is true, written a book about Koevoet, based on interviews with ex-members, but that is that. Secondly, not a single black member of the then security forces has dared to present his story to the world.

In this book, Sisingi Kamongo, nicknamed Shorty, fills these two lacunae. Kamongo, who hails from the Kavango, was a black member of Koevoet who fought in the 80s in Ovamboland and the Kavango against SWAPO insurgents. For the first time, the public may now view the war through the eyes of a black man on the South African side.

Kamongo has indeed a story to telland what a story. His remarkable memory is proven by the statistics of the various fights he describes and from the verbatim quotes of radio conversations. More importantly, he explains why he fought on the side of the South African racists, and against SWAPO, which was, after all, recognized by the United Nations as the only legitimate representative of the Namibian people.

Kamongo does not spare his readers. He tells of the contacts, the sweat, blood and guts. Without him spelling it out expressly, his story illustrates the blunting effect on feelings which every war has. He relates very honestly the human-rights violations which he and fellow members committed against SWAPO prisoners. But he also makes clear that the political propaganda against Koevoet was highly exaggerated, that it was a very disciplined unit, that those guilty were strictly, and sometimes summarily, punished. He places this propaganda in the context of war, of the crimes SWAPO itself continually committed and the bitterness this created with him and his comrades. (As a matter of factand Kamongo does not go into itbut SWAPOs crimes against its own supporters in exile have been excellently documented.)

Kamongo does not hide his bitterness against the then South African government. Though he and his fellow black members of Koevoet often put their lives on the line (he himself was thrice wounded severely), they were paid a small salary of just R280 a month together with head money for insurgents killed or captured. And when SWAPO took over, they had to flee for their lives to South Africa, with no help from the South African government, without recognition, with nothing. Today they live in poverty, Kamongo in a wheelchair because of his wounds.

To what extent is Kamongos story simply a question of self-justification? This is a legitimate question. Memoirs like those of Generals Malan and Geldenhuysand othersalways contain an element of that. There can be no doubt that Kamongo tries to justify his actions, and undoubtedly some people will not be convinced by it. So be it.

But this does not detract from the fact that his is a dramatic story, which is told factually and soberly, without too much commentary. After reading this book, everyone is entitled to think what he wants about Kamongo and his case. But what nobody can deny is that Kamongos story is worth telling, even less so that he has done it well. I am glad that I made Sisingi Kamongos acquaintance by reading the manuscript. It was an enriching experience.

Leopold Scholtz

Brussels

March 2011

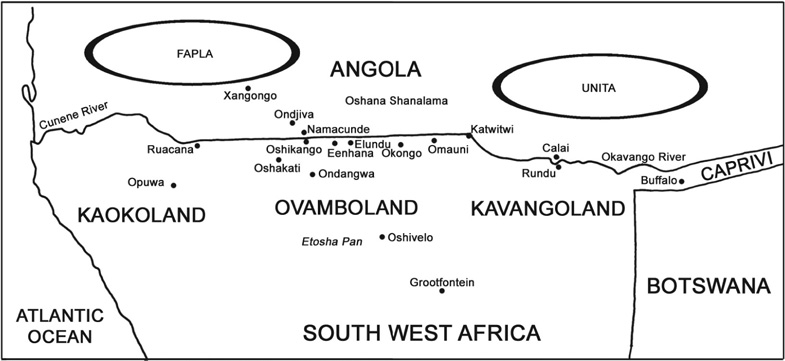

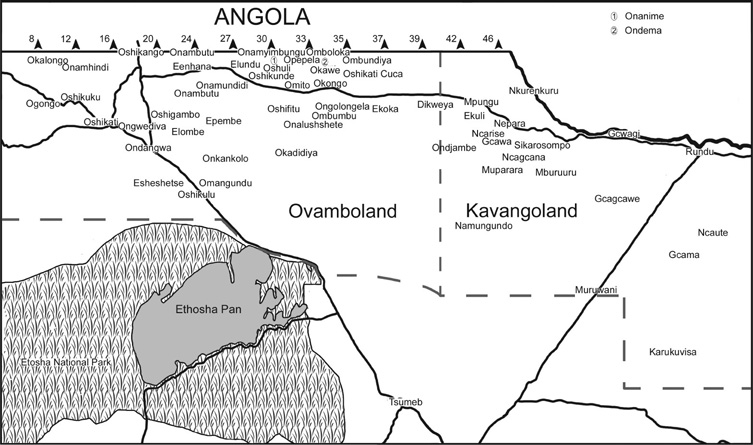

ANGOLA AND NAMIBIA

Ilse van Staaden

Ilse van Staaden

by Leon Bezuidenhout

Shadows in the Sand is the story of Special Sergeant Sisingi Shorty Kamongo, a Koevoet tracker in the Namibian insurgency bush war. The appendices include accounts from Koevoet combat team leaders, Francois du Toit and Herman Grobler; the story of a (previously) inexperienced SADF Ratel gunner, Jacques Myburgh, who gives his account of a day spent in action with Koevoet in April 1989, is also included.

Next page