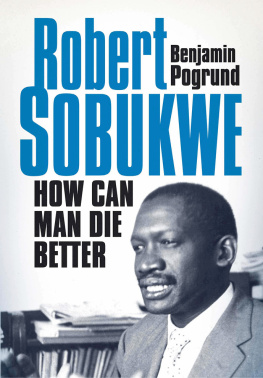

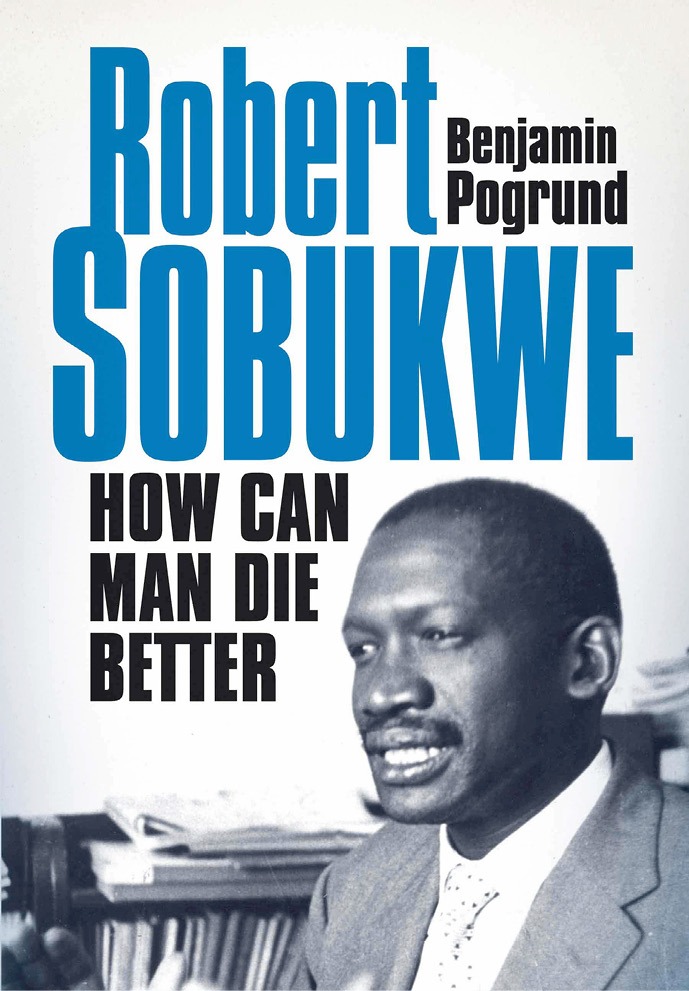

Book Description

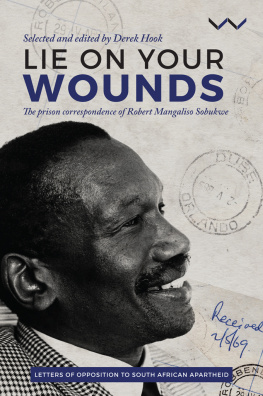

I am greatly privileged to have known him and to have fallen under his spell. His long imprisonment, restriction and early death were a major tragedy for our land and the world.

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU on Sobukwe

On 21 March 1960, ROBERT MANGALISO SOBUKWE led a mass defiance of South Africas pass laws. He urged blacks to go to the nearest police station and demand arrest. Police opened fire on a peaceful crowd in the township of Sharpeville and killed 69 people.

This protest changed the course of South Africas history. Afrikaner rule stiffened and black resistance went underground. International opinion hardened against apartheid.

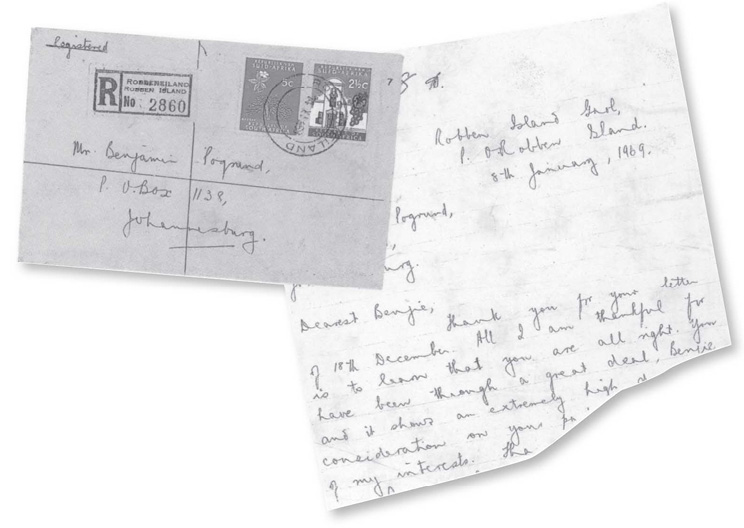

ROBERT SOBUKWE , leader of the Pan-Africanist Congress, was jailed for three years for incitement. At the end of his sentence the government, fearful of his power, rushed the so-called Sobukwe Clause through Parliament to keep him in prison without a trial. For the next six years Sobukwe was kept in solitary confinement on Robben Island, the infamous apartheid prison near Cape Town.

On his release Sobukwe was banished to the town of Kimberley with very severe restrictions on his freedom. He died there nine years later in February 1978.

This book is the story of this South African hero the lonely prisoner on Robben Island. It is also the story of the friendship between Robert Sobukwe and BENJAMIN POGRUND , whose joint experiences and debates chart the course of a tyrannical regime and the growth of black resistance.

Title Page

ROBERT SOBUKWE

HOW CAN MAN DIE BETTER

BENJAMIN POGRUND

JONATHAN BALL PUBLISHERS

JOHANNESBURG & CAPE TOWN

Dedication

For

Miliswa, Dalindyebo, Dedanizizwe, Dinilesizwe,

Jennifer, Amanda, Daniel, Gideon

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

This reissue in paperback of t he biography of Robert Sobukwe contains the same text as the original edition published in 1990 in Britain, and then in the United States and South Africa. Events have moved on since then and some people who are quoted in the text are no longer alive. But the story remains the same and is brought up to date in the new Epilogue.

The text was originally written in London, to where I emigrated in 1986 after the closing down of the Rand Daily Mail by its commercial owners, Anglo American Corporation, under pressure by the South African government. The Mail paid the price for being too successful in exposing apartheid evils. After eight years in London I went to the United States as editor of an international newspaper based in Boston. In September 1997 I came to Israel as founding director of Yakars Center for Social Concern to promote dialogue across lines of division.

The memory of Robert Sobukwe is strong and I am more grateful than ever to all those who have helped, then and now, to keep it so by sharing their experiences and views about this gentle, parfit man. As I said in the original edition, I owe particular thanks to Randolph Vigne, who read the text and offered a host of informed and constructive comments; to Hamilton Zolile Keke, who was always cheerfully willing to share his knowledge; to the late Dennis Siwisa, who read the text and who was a source of invaluable information. And I again thank Veronica Zodwa Sobukwe, not only for many years of friendship but also for her support in the writing of this book and for reading the original text. Simon Richardson was an authoritative and co-operative editor and his imprint remains on the text.

I again wish to thank Humphrey Tyler for permission to publish his report on the Sharpeville shooting; Jan Tystad for allowing reproduction of a report he wrote for Dagbladet , Oslo; The Times , London, for permission to publish excerpts from a column by Nicholas Ashford (an admired friend who died on 10 February 1990); and The New York Times in regard to a column by Anthony Lewis.

Jonathan Ball, the head of Jonathan Ball Publishers, has believed in this book from the start and has supported several reprintings and now this new edition.

Despite the help and goodwill of so many people, I bear full responsibility for the information and views for what is, ultimately, a personal view of Bob Sobukwe.

Finally, my gratitude to my wife, Anne, for sharing so much with me and Bob, and for lovingly sharing the adventures of life with me in the years since then.

Benjamin Pogrund

Jerusalem

2006

The story is told in War of Words: Memoir of a South African Journalist by Benjamin Pogrund, foreword by Harold Evans, published by Seven Stories Press, New York and London, 2000; M&G Books, Johannesburg, 2000.

Preface

Preface

Then out spake brave Horatius,

The Captain of the Gate;

To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late.

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of the Gods?

Thomas Babington Macaulay:

Lays of Ancient Rome, Horatius

As the sky began to lighten on a late summers morning in South Africa, Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe left his home in Soweto to walk to the nearest police station. He was going to demand that he be arrested.

Six other men were with him. Three more joined them during their walk of 4.5 kilometres. All were blacks. Each newcomer received a salute, right hand raised, the palm open, and a sonorous greeting iAfrika Zulu and Xhosa for O Africa! Each responded with the same salute and the cry, Izwe Lethu Our Country.

Workers on their way to trains and buses to get to jobs in the city of Johannesburg looked at them with curiosity; some greeted them, others hurried to be away from them.

An hour later, by 7.30 a.m., Sobukwe and the small group were at the Orlando police station, a single-storeyed building, the walls and roof made of corrugated iron. They halted outside the high wire-mesh fence and waited for others to arrive. They were uncertain about how many might come. Eventually, about 200 men gathered there, with a cluster of women to wish them well.

It was Monday, 21 March 1960. For Sobukwe, it was the day that South Africa was to be transformed by what he had termed positive action against the pass laws.

Until abolished in July 1986, these laws were the basic method used by white authority to control the countrys black majority. The laws determined where blacks could live and work, and even what work they could do. Every black adult, both men and women, had to carry an identity document the pass. Officially, it was known as a reference book. Blacks, however, called it the dompas Afrikaans for stupid pass.

The pass had to be carried at all times, to be instantly produced when demanded by a policeman. Failure to have the pass available courted instant arrest, prosecution and a fine or jailing. Even more important, the pass contained details of a black persons status: whether he was allowed to be in a particular area or city. A person found where his pass did not specify he was allowed to be was also subject to immediate arrest.

In 1958, the number of convictions of blacks under the various control laws considerably less than the number of arrests was 396,836. This was an average of 1,087 on each day of the year, weekends included, in a total black population of less than eleven million. The pass laws were responsible for about one-third of the criminal convictions of black people.

The pass laws were hated as the tangible evidence of black subjugation, and for their ravaging effects on the lives of millions upon millions of people.