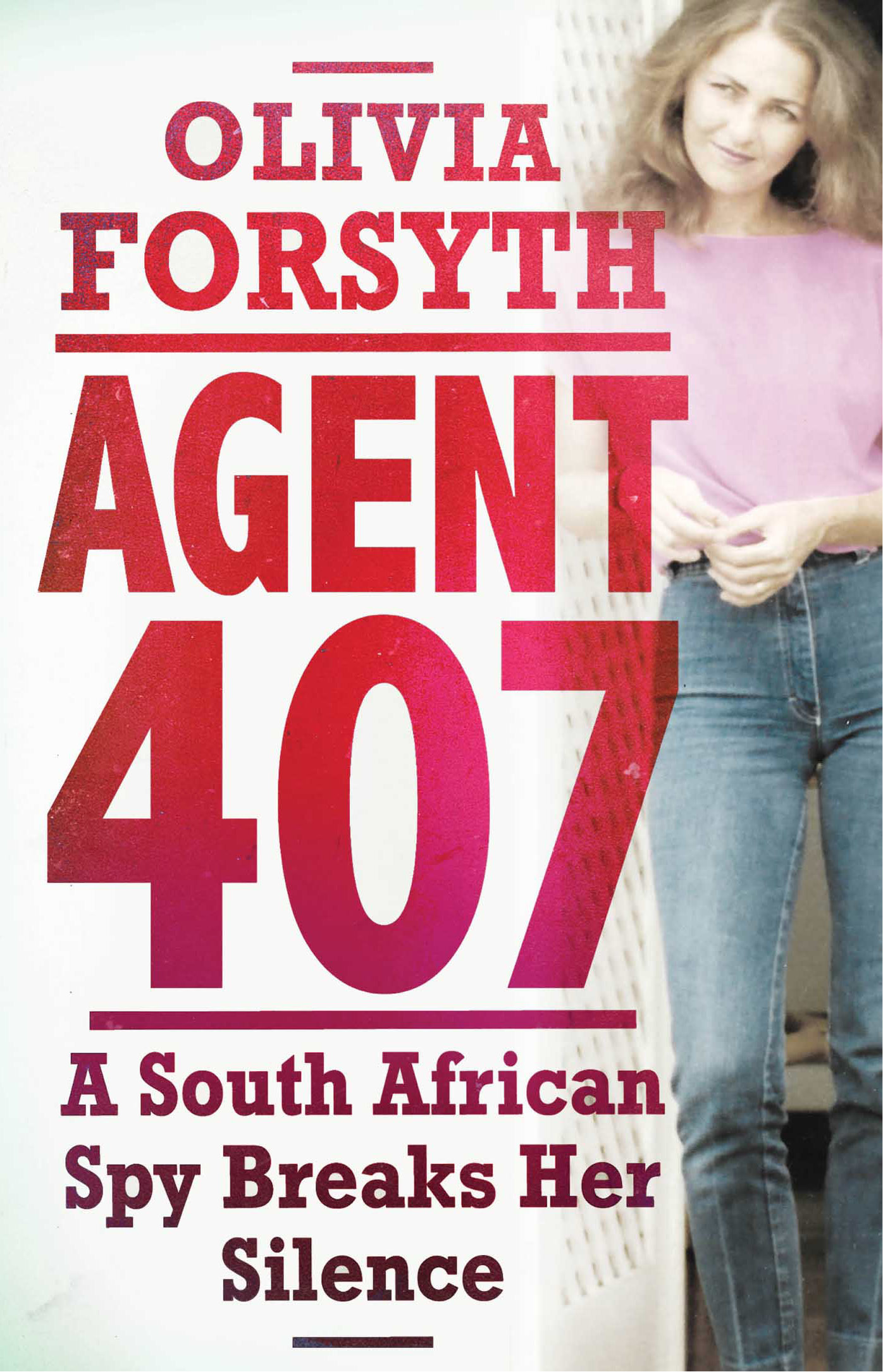

This is the story of Olivia Forsyth, also known as agent RS407, codename Lara, lieutenant in the Security Branch of the South African Police, ANC comrade Helen Bronson, prisoner Thandeka, alias Christine Smith.

I owe it to many people, and to myself, to set the record straight. There have been many versions of parts of the story in the press over the years, many lies overlaid with truths and truths overlaid with lies. Much of the truth is just a palimpsest, an echo that changes even in the act of repeating it, but this is my story. I wish it were an heroic tale, like those of the many good people involved in the struggle for freedom in South Africa who did not hesitate to put themselves in the firing line. But it is just the story of one white South African woman who found herself on the wrong side.

A very good man put his trust in me to write this story well, and I have tried not to let him down.

Chapter 1

Unfinished Business

Ministerial residential complex, Cape Town, December 2000

Not for the first time, my life has a strangely fictional quality, as if it doesnt belong to me. I am leaving South Africa in a few days time, to take my children to live in the United Kingdom. And, also not for the first time, my fortuitous birth in the UK is providing me with an escape route.

But before I can leave there is some unfinished business to which I need to attend.

I have made the decision to write my story. There are a myriad reasons for this: my own catharsis, a strong desire for my children to know the real story about their mother, so that my extended family, friends and acquaintances will know the truth after all the subterfuge, the lies, the cover stories, and the fictional covers. Most of all, perhaps, I am going to write it all down to do as my mother always urged her children when we had transgressed to make an act of contrition.

But if I am going to write my story, there is one person with whom I need to discuss it first, the person to whom I owe my life. His sanction is essential to me, although it is not the primary reason I need to see him. First, I have to tell him the truth about what happened and then I need to ask his forgiveness.

There have been two such people in my life, but one of them was brutally gunned down and murdered. Now there is only one.

Ronnie Kasrils. Comrade Ronnie Kasrils.

When I met him he was chief of staff of Umkhonto we Sizwe, Spear of the Nation, the armed wing of the African National Congress. Now he is a government minister in the South African cabinet. I did think they could have done more for him than assign him the portfolio of Ministry of Water Affairs, but being the good, obedient soldier he was, I knew he would work wherever he was sent.

I had contacted Ronnie Kasrils through a mutual acquaintance, and he had generously and immediately agreed to see me. I was to come to Cape Town, to his residence, for a meeting at 8pm on an evening in December. I was delighted and relieved. I had not been sure how he would respond. Certainly I would not have blamed him if he had wanted nothing to do with me.

As soon as the car stops at the unobtrusive security gate in a quiet, tree-lined street which is the entrance to the ministerial residential complex, a guard emerges from a red roof-tiled guardhouse and approaches. I have not come alone. My friend Susan and her husband Hugh have driven me here. From the passenger seat, I inform the guard of my appointment and he gives us directions and waves us through. The complex, which resembles a genteel, upmarket gated village, with grand houses dotted discreetly around the sculptured grounds, was purpose built by the apartheid government as the official abode for ministers when parliament was in session in Cape Town. In the new South Africa, it still houses ministers, but mostly now the people who live in them are stalwarts of the anti-apartheid struggle.

We drive slowly towards where we think the house is, winding through the beautifully landscaped gardens, but the next thing we know we are lost. We continue driving aimlessly for a while, somehow hoping well see the right place. Then, suddenly, help appears in the peculiar guise of Kader Asmal, who is sitting on the porch of his house, in his pyjamas and dressing-gown, a fluffy white dog on his lap. It is probably a Maltese poodle but the best description I know for this sort of small creature, known for its excitable yapping, is stoep-kakkertjie and it has no appropriate English equivalent that I can think of. Kader Asmal is a much revered stalwart of the struggle and a founder member of the Anti-Apartheid Movement in both Britain and Ireland. He is also now the Minister of Education, having recently, coincidentally, handed the post of Water Affairs to Ronnie Kasrils. It feels strange stopping to ask the great Kader Asmal for directions. He is affable, however, and points Ronnie Kasrilss house out to us, which is in fact close by. We thank him sheepishly and continue on our mission.

At the house, Susan and Hugh wait in the car while I go inside to find out what time I can ask them to return to fetch me. Susan, one of my dearest friends, who now lives in Cape Town, is one of the few people whom I have told the truth, and she is just as excited as I am about this meeting. Outwardly, at least, her excitement is much more evident.

I climb the few steps to the front door and knock. I am somewhat taken aback when the minister himself comes to the door: I had been expecting a bodyguard. His smile and his greeting are genuinely warm and welcoming. He clasps my hand and kisses me on the cheek as if nothing has happened, making me feel more ashamed than ever. The first strangeness is that I am not sure what to call him. Comrade seems the right thing, but also not appropriate now; I feel I no longer have the right to call him comrade, not after the betrayal, and Ronnie feels too familiar. Mr Kasrils is too formal for someone I knew so well, and who knew me so well too.

He walks me to an upstairs room in this modern villa, a large open-plan space that looks like his study or a family room. It strikes me that there does not seem to be anyone around at all, although later in the evening I can hear some movement somewhere in the house, and I hear him talking to someone when he goes to fetch us a pot of tea.

We skirt around a few niceties, make a few bits of phatic conversation. When I find the opportunity, though, I plunge in. I try to recount what happened, attempt to explain why I took the decisions I did. He listens patiently. My explanations sound lame to me, mere hollow words after all these years, and pathetic in the context of the struggle as a whole, but my apology is sincere. I am deeply sorry for the embarrassment I must have caused him, after he had taken a personal risk in trusting me and believing in me. I had not been able to live up to his expectations. Sitting here across from this man, I feel small, humble, emotional.

When I am finished, his reaction astounds me. There are no recriminations, only kindness and understanding (although he does admit that I had caused him great embarrassment).