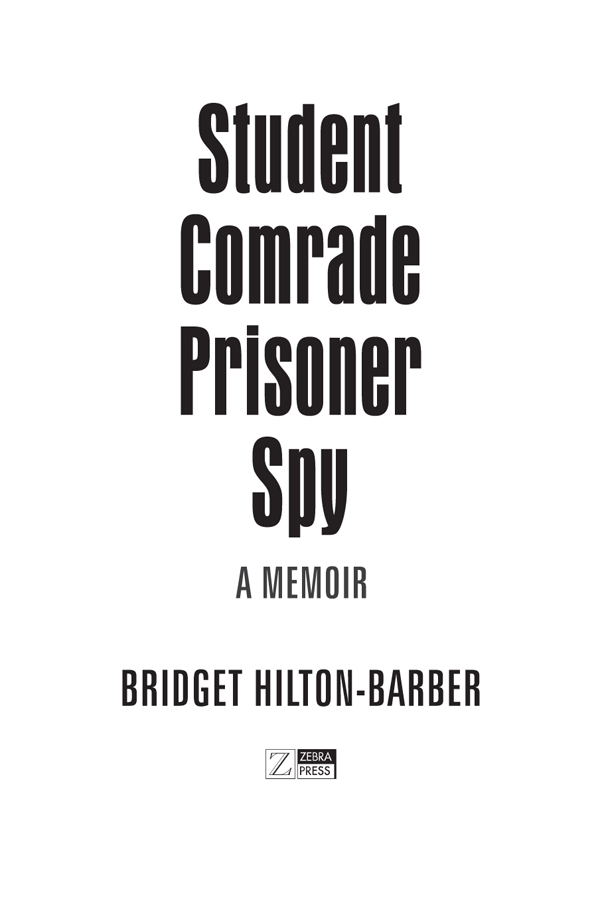

Published by Zebra Press

an imprint of Penguin Random House South Africa (Pty) Ltd

Reg. No. 1953/000441/07

The Estuaries No. , Oxbow Crescent, Century Avenue, Century City, 7441

PO Box 1144 , Cape Town, 8000 , South Africa

www.penguinrandomhouse.co.za

First published 2016

Publication Penguin Random House 2016

Text Bridget Hilton-Barber 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners.

All photographs by Steven Hilton-Barber or from Bridget Hilton-Barbers personal collection.

Lyrics to Suburban Hum reproduced with kind permission of Jennifer Ferguson.

Lyrics to National Madness, by the Aeroplanes, reproduced with kind permission of Michael Rudolph.

Lyrics to Shot Down in the Streets, by James Phillips, reproduced with kind permission of Lloyd Ross.

PUBLISHER : Marlene Fryer

MANAGING EDITOR : Robert Plummer

EDITOR : Lynda Gilfillan

PROOFREADER : Bronwen Maynier

COVER DESIGNER : Ryan Africa

Set in 11.5 pt on 16.5 pt Adobe Garamond

ISBN 978 1 77022 800 9 (print)

ISBN 978 1 77022 801 6 (ePub)

This book is dedicated to Ruth Becker,

great friend and soul sister

Contents

Most things are forgotten over time. Even the war itself, the life-and-death struggle people went through is now like something from the distant past. Were so caught up in our everyday lives that events of the past are no longer in orbit around our minds. There are just too many things we have to think about every day, too many new things we have to learn. But still, no matter how much time passes, no matter what takes place in the interim, there are some things we can never assign to oblivion, memories we can never rub away. They remain with us forever, like a touchstone.

Haruki Murakami, Kafka on the Shore

Prologue

I AM ON THE road to hell. The N from Port Elizabeth to Cradock, paved not with good intentions, in fact barely paved at all, but potholed and crumbling at the shoulders, truncated with an annoyance of stop-and-goes. Its the middle of winter in the middle of nowhere where the mountains are the colour of burnt toast and the flaming-orange roadside aloes hurt my bleary, hungover eyes.

I am researching this book, my book, our book, about the apartheid days, a time when I was a student in the Eastern Cape. When the land was caught in an evil magic, and the security police unleashed their snapping-snarling-slavering dogs: the roadblocks, the round-ups, the raids, the torture and screening centres, the splash rooms, the scrubby badlands behind desolate sand dunes.

I am not just on the road to hell, but flashbacking to the time when this roads signposts read Imprisonment , Poisoning , Disappearances , Murders , Torture . All about me in the burnt-toast mountains hangs the ghastly soundscape of history as people were shocked and helicoptered, dangled over cliffs, beaten into comas, shot in the back, all in the name of racist apartheid.

I have left the dregs of the whisky at my cousin in PE and I am worn down from what she calls a hondnaaipoesfok hangover. Its appropriate to travel the road to hell with a hangover from hell, I guess a real sonofabitch. Ever since I can remember, wrote Laurens van der Post in The Lost World of the Kalahari , I have been struck by the profound quality of melancholy which lies at the heart of the physical scene in Southern Africa. I recollect clearly asking my father once: Why do the vlaktes and koppies always look so sad? He replied with unexpected feeling: The sadness is not in the plains and hills but in ourselves.

I am not the only person on the road to hell. Behind me, and hell be behind me all the way from the Port Elizabeth turn-off to Cradock to Cradock itself, is the most grim-faced truck driver I have ever seen. He is concrete-jawed, hollow-eyed, his brow an anxious concertina. At every stop-and-go he just stares straight ahead. He doesnt acknowledge me. Even when I get out at one, shivering in the miserable winter as I give him a desultory thumbs-up, he just stares straight ahead.

The road to hell is suitably hellish. I nearly get mugged in Cookhouse at a garage off the highway. As I drive into the forecourt my car is surrounded by a gang of feral tik-head okes, guys they used to call Bushies in the bad old days half-coloured, half-Xhosa. As my windows darken, I put foot and drive away, heart thumping, adrenaline pumping.

The final stop-and-go is just before Cradock and Lingelihle township, on the outskirts of which stands the monument to the Cradock Four, soul epicentre of my book in many ways. Four giant perpendicular slabs for four men who were murdered by the Eastern Cape security police in 1985 . They were beaten, set upon by dogs, stabbed, doused with acid, burnt. Its a peculiar monument, stark and Stalinist, windblown, empty but full of stories about embezzlement and mismanagement. Stinking of whisky and thinking of the sadness of the Cradock Four, I sit doleful in my car, reflecting. None of the widows ever remarried, you know. And then the truck driver behind me gets out of his cab, and as he walks towards the scrub for a pee, I catch a glimpse of his T-shirt. It says: 1 295 days without smiling.

PART ONE

BURNING WOMAN

1

Train to Rhodes

Y OU DO REALISE you can never live at home again, says my mother, Tana, cheerily as she puts me on the train to Grahamstown in February 1982 . I am crying. Well, except of course for the holidays, she adds, and thrusts into my curled-up, tear-stained paw her well-worn copy of Robert Carriers Gourmet Cooking . Youll find the basics of everything in here.

It is on the insistence of my parents that I am getting on the train to Rhodes. I wanted to take a gap year and travel like other school friends but for once they put their foot down. Education is everything. Pick a subject and go.

The youngest of three, my middle brother, Steven, will meet me at the other end. Brett, the oldest, has just come out of the army and just in time too; national service has been extended to two years.

Mercifully, I havent been able to find a place in res I am already a rebellious young thing and cant bear the thought of teddy bears on lacy pillows, Garfield posters, frilly nighties, all that pink girly kitsch. My style is incense holders and antique tins, posters of classic movies. My blonde hair is long and curly, ungovernable, and I generally wear hippie-style Indian dresses, cotton shirts and long skirts from the Oriental Plaza in Fordsburg. I have pierced ears and my forearms are covered in bangles, my fingers in rings, and on my feet I wear shiny black Chinese slippers.

Okay then, poppet, says my father, David, as he cheerfully opens the bottle of wine theyve brought along in celebration of my departure for my new life. My parents are already looking far too relieved and have an unnerving glint in their eye.

Our gathering on the platform is a small, white huddle, collectively somewhat anxious. Sending children far away in difficult times. It is 1982 , after all. Apartheid South Africa is ruled by an oppressive white regime. A greatly divided nation, its leader is the finger-wagging Groot Krokodil, P.W. Botha, whose bald head and shiny face with fleshy jowls atop a thick neck fills our TV screens to warn us of die rooi gevaar , die swart gevaar , any and every kind of gevaar . Everything is a danger and communists and blacks are the worst. We have a sinister minister of law and order, Louis le Grange, whose name will leave a horrible stain in the history books. Blacks live in separate areas and must carry a passbook. Obviously, they cannot vote. There are few amenities in their drab, crime-ridden townships, while whites are protected and coddled in comfortable suburban enclaves.

Next page