Copyright 2019 by Boyd Varty

Illustrations by Roxy Burrough 2019 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Varty, Boyd, author. | Burrough, Roxy, illustrator.

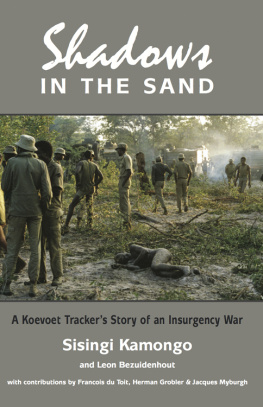

Title: The lion trackers guide to life / Boyd Varty ; illustrations by Roxy Burrough.

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019002731 (print) | LCCN 2019003935 (ebook) | ISBN 9780358100492 (ebook) | ISBN 9780358099772 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780358172154 (audio)

Subjects: LCSH: Varty, Boyd. | Londolozi Game Reserve (South Africa) | Lion huntingSouth AfricaLondolozi Game Reserve. | Tracking and trailingSouth AfricaLondolozi Game Reserve. | Wildlife conservationSouth AfricaLondolozi Game Reserve.

Classification: LCC SK575.S 5 (ebook) | LCC SK575.S5 V 375 2019 (print) | DDC 639.97/9757dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019002731

Cover design by Brian Moore

Cover Illustration by Roxy Burrough

Author Photograph Amanda Ritchie

v2.1019

For my father, who has mentored so many

There are many varieties and specializations among shamans, but generically they were called Ajcuna, signifying he or she who tracks it.

MARTN PRECHTEL , Secrets of the Talking Jaguar

Acknowledgments

It takes a village. This book has been the culmination of many years living on the track of my own life. I have spent a lot of time outside the conventional paths on trails of my own making. While this is a beautifully rewarding path, it can be lonely and it will put you face-to-face with your own doubts. I would not be able to live as a tracker without the incredible support I have received from my family, extended family, and village.

I thank my mother and father for always being an example of making their own path and for endless love and support. My sister, Bronwyn Varty Laburn, has been one of my greatest teachers, and her guidance has allowed me to keep moving forward. My brother-in-law, Richard Laburn, was a critical support in the early phases of the book and continues to be.

Martha Beck provided so much of my education as an inner tracker and I will always be profoundly grateful for the gifts she has given me, including the ongoing encouragement to write and to follow my inner track.

To the shaman who apprenticed me: thank you.

I thank Tamara Day Shriver and Harry Kalmer for their assistance in creating this work as readers, curators, and fellow storytellers.

Koelle Simpson has been a true friend and encouraged me in living the ideas shared between these pages.

I am deeply grateful to Betsy Rapoport for her unwavering support and willingness to help me get my ideas out, as well as for always welcoming me as a weary traveler to her home.

A deep word of thanks to Tess Beasley and Maureen Chiquet, who have given me incredible assistance and provided the sanctuary that has allowed me to live with many unknowns.

I thank Tina Bennett, my agent, for the incredible guidance she provides as a reader, friend, and guide in the world of publishing. Thanks for taking a chance on me early on.

I am grateful to Lisa White, my editor at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, for helping me shape this text.

I thank the owners of Londolozi Game Reserve for being custodians of a unique and sacred place. Londolozi is the home of the restoration, and it would not have been born or fostered without the wisdom of Allan Taylor, John Varty, and my parents, Dave and Shan.

I thank Alex van den Heever and Renias Mhlongo for their friendship and mentorship. Our many hours in the bush together have been a gift I will treasure to the end of my days.

Last, I thank all life trackers the world over. The tracker finds a path where there isnt one, and we need that more than ever.

Prologue

I wake at 3 a.m. from that strange midway zone that comes with jet lag.

Outside the open sliding door of my bungalow, the night is silver with moonlight.

Cool winter air seeps in through the mesh of the screen. A scops owl calls every ten secondsprrr prrrr prrrinto the stillness.

I am home. Home in a physical sense. My body knows this place and these night sounds. After months away in the United States, my childhood in the African bush comes flooding back in sensory memories: the smell of the bushveld at night, the unique tone of moonlight, the eternal feeling that the night is somehow happening inside me as it happens around me.

I hear branches snapping like cap guns as an elephant feeds down in the river. High in the ebony tree next to the cottage, a baboon barks into the night: raaaaahhhh hoooo raaaaahhooo.

Then, a beat of deep stillness followed by a lion roaring back.

The sound of the lions roar is the threshold telling me I have stepped from one world to another. After so many nights abroad filled with artificial light and the hum of appliances, there is no truer sound of being home. The timbre of the call, the way it rolls through the cold night air to find me. Its powerful vibrations shudder the door on its hinges. My heart instinctually skips with excitement.

The renowned writer of the African wilderness Laurens van der Post said of the lions roar that it is to silence what the shooting star is to the night sky. It is like waking from a dream and having the sensation of being pulled back into my body, as if my soul were being pulled from its endless seeking back into myself by the beauty and power and violence of that ancient sound.

Lying in my bed now, I know the lion is out there in the night. Somehow, more deeply than I can rationally understand, I know his presence is important to me.

Something primal in a part of my brain that stretches back through time barges past the groggy jet-lagged traveler and becomes perfectly and instantly present. Something wild in me is waking up.

I have spent the past ten years charting a strange path between worlds, between my home in the South African wilderness and the fast pace of modern life in the United States. I worked first as a life coach in personal development seminars, then as an apprentice to an indigenous healer. My work has given me a front-row seat to the catalog of illnesses long associated with modern life. Over the years, in conversation after conversation, the themes were the same: abuse, isolation, anxiety, depression on the one hand, and on the other hand an innate creativity and desire to effect change. I saw a deep longing in people to give of themselves, to belong once more to each other and the natural world. So many people I spoke to were searching for a life that felt more meaningful. As was I.

In fact my seeking had taken me all over the world. I had immersed myself in the art forms of personal transformation: Zen meditation, psychology, somatic bodywork, and martial arts were just a few. And yet still I felt there was something I was meant to do that I had not yet discovered. I could sense it out beyond my rational life plan. I could feel its faint edges whispering. I was looking for something. I had found pieces of my own authentic life in wilderness, coaching, South Africa, and Americabut how did it all tie together?