Contents

Guide

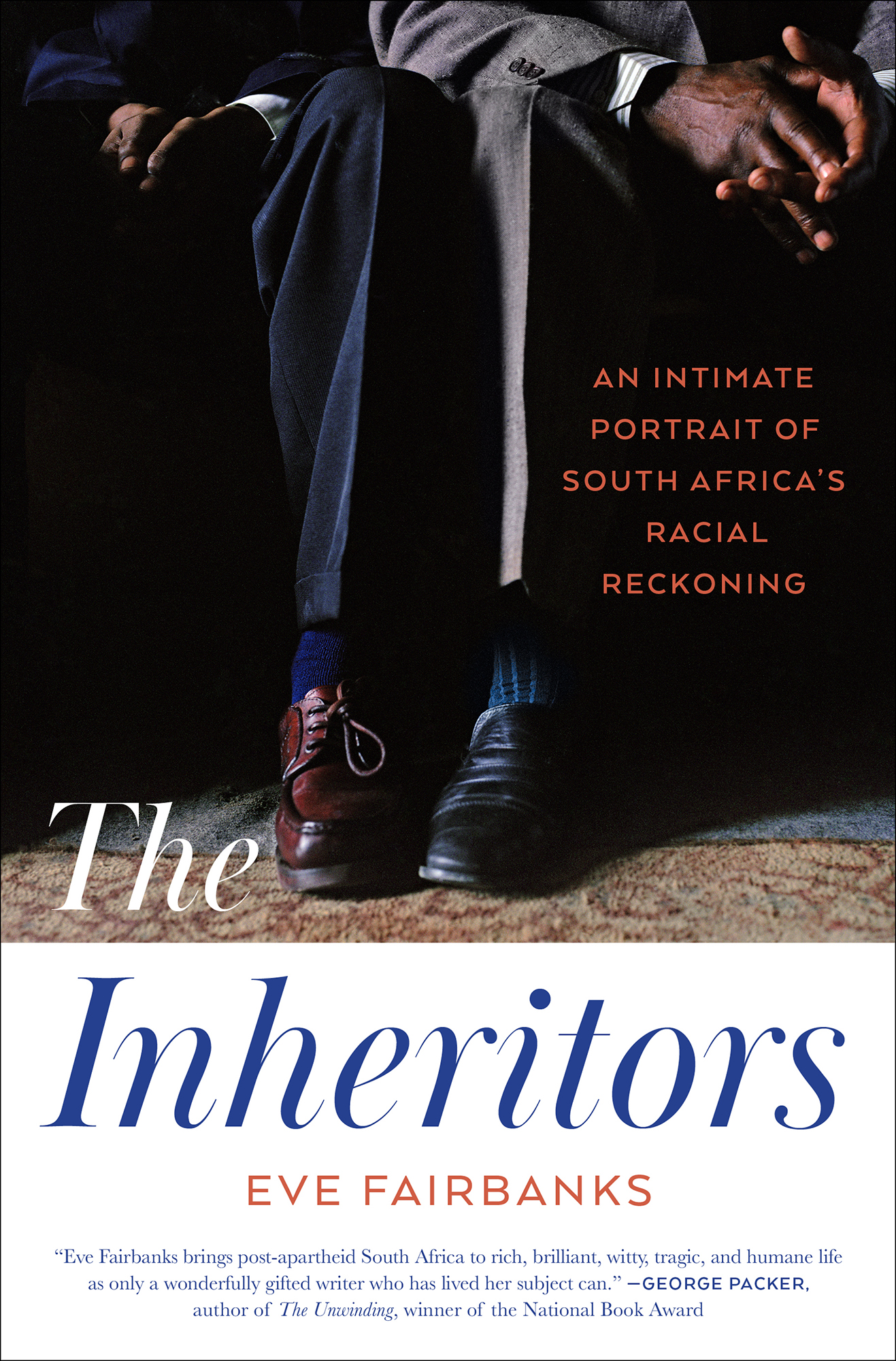

An Intimate Portrait of South Africas Racial Reckoning

The Inheritors

Eve Fairbanks

Eve Fairbanks brings post-apartheid South Africa to rich, brilliant, witty, tragic, and humane life as only a wonderfully gifted writer who has lived her subject can. George Packer, author of The Unwinding, winner of the National Book Award

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2022 by Eve Fairbanks

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition July 2022

Small portions of this book first appeared, in different form, in The New Republic, The Guardian, Moment magazine, and publications of the Institute of Current World Affairs.

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Lewelin Polanco

Jacket design by Natalia Olbinski

Jacket photograph by Marc Shoul

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-4767-2524-6

ISBN 978-1-4767-2529-1 (ebook)

My inheritance has become for me like a lion in the forest.

Jeremiah 12:8

A Note on Usage

M OST S OUTH A FRICANS USE THE lower case for the adjectives black and white, as in black South African voters or a white farmer.

To refer to some South Africans as black was an innovation by Steve Biko and others in the countrys 1970s Black Consciousness movement. Though skin color long dictated the way people moved and lived in South Africa, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the more commonly used adjectives were European, African, Bantu, anda bit laternon-white.

Biko believed the apartheid government treated South Africans as a mass when it suited themas in when it denied everyone who was not European the full right to voteand divided them when it suited them, too. It divided people who spoke Bantu languages from South Africans of Indian descent and so-called colored people, or South Africans of mixed racial heritage. And it sought to divide those who spoke Bantu languages further by tribeinto the Zulus, the Sothos, and so on, to whom it apportioned separate territories.

In his writings advocating that his fellow black South Africans embrace the word black and become proud of it, Biko mostly used the lower caseas did the African National Congress, South Africas leading black-liberation movement, and most subsequent black South African thinkers and writers. When white government leaders began to use black and white, they typically used the upper case to underscore their contention that Black and White people, in South Africa, were cultures as distinct, long-standing, and defining as the Persian or Chinese peoplesseparate tribes that might have commerce with each other but could never really become one nation. To capitalize the words White and Black was the apartheid governments attempt to seize back some semantic power.

I thus use white and black in the pages that follow, unless a quoted passage deployed a different usage or the person with whom I spoke wanted me to do otherwise.

Prologue

S HE SET OUT AT NIGHT . That was how it worked in Soweto: black people woke before dawn because it took hours to get to work on the buses to the formerly white-only city. From as long as she could remember, Malaika would hear men and women rising at 4:00 a.m. to stoke coal fires to make tea. The walls of the shack she lived in with her grandmother, her mother, her auntwhom she called her sisterand her uncles were made of sheets of corrugated iron and the shacks were so close to each other she could hear the people living three homes away waking up, their grumbling and the clattering of their pots.

Shed always try to go back to sleep. But when she was eleven, she had to start to wake up at that time, too. Her mother enrolled her in a formerly all-white school across the ridge, and the bus ride took two hours. When she got up from the blanket on the floor she used as a bed, the stars had already set, and the haze leaking into the shack from her neighbors fires made her trip over her grandmothers still hot stove, burning her arms.

But it was worth it, she told herself. In the dark she clipped her hair, packed her backpack, put on her uniforma black skirt and a bright turquoise sweater with a pink-and-purple crest embroidered on the breastand waited for one of her uncles to walk her to the bus stop.

If she couldve had one wish, it wouldve been to walk with Godfrey, her favorite of her mothers brothers. The other two uncles who lived with her played dice on the streets to earn pocket money and seemed to her, already, to have the manner of grandfathers, grumpy and cynical.

But Godfrey was sober, beautiful, ageless. He never looked, she thought, like a Soweto man. He worked hard, but whenever hed come home hed bring a different aura into the shack. He wore new shoes and gorgeous dress shirts with a few buttons left open at the top to expose his velvety chest. And he was kind, getting down onto the floor no matter what he was dressed in to talk and laugh with Malaika. His laugh was like the electric lights they often didnt have; when Godfrey laughed, she could forget the power in the shack only worked some of the time.

Her country, South Africa, only integrated racially in 1994, when she was two years old. There had always been a primary school for black childrenwho were kept out of white neighborhoods by the most rigid system of racial segregation the modern world has ever knowna fifteen-minute walk away. But her mother implied the point of going to the formerly white school, now that she could, was to be more like Godfrey when she grew up: empowered, loose, and free. Godfreys job took him to places with amazing things. When hed come home, hed bring bags full of food, pretty jewelry, and candies with creamy centers the hawkers in Soweto didnt sell. She knew, because she had tried them all. Where did you get those? she would ask him.

In Never-Never, Godfrey would laugh.

That was where he told her he worked. Never-Never. He said the furniture was made of chocolate there and the gutters flowed with liquid gold. She wasnt sure whether to believe that, but it had to be a wonderful place if it made Godfrey so happy. Being with him made her forget the reason she needed a chaperone in the street. Walking in Soweto wasnt safe, people said. Muggers could crouch behind the thigh-high piles of trash along the way and attack little girls. Her new school actually sent a bus to Soweto that took black students directly to its doorstep, but Tshepiso, her sister, was so ashamed of the familys shack she refused to let the other kids on the school bus see them picked up there.