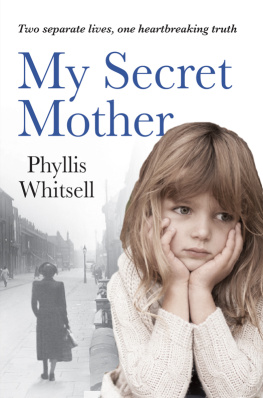

The rights of Phyllis Whitsell to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted, in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior

written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of

binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar

condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Names and personal details have been changed COVER IMAGES: Topfoto, iStockphoto, Trevillion Images

introduction

Letter to Bridget

February 22, 2018

Dear Mum,

It is 61 years ago to the day that you walked into Father Hudsons Home, an orphanage in Birmingham, and handed me over to the Moral Welfare Officer. I cannot imagine what must have been going through your mind when you gave the warm bundle of your nine-month-old daughter to a stranger, and left with empty arms and a broken heart.

I know that youd tried so hard to keep me. After giving birth you refused to give me up for adoption, took me home and did the best you could. For a while it looked like youd tricked fate and stood firm in the face of the authorities who, back then, routinely separated unmarried Catholic Irish girls from their illegitimate babies. We wouldnt stand for it now, but those were different times, brutal times, and it shows me how strong you really were to even try to keep me.

But it wasnt to be.

You were battling terrible odds. Your life had been unbelievably hard; you had terrible experiences growing up in Tipperary, and were left alone and defenceless. You sank into despair, a despair made worse by the comfort you sought from drink and with no chance of a normal happy life. I feel so sad knowing that, underneath the turmoil and drunkenness, was a woman desperately seeking love, desperate to be a mother to her child, but who was simply unable to cope.

Our story began again when I found you, on November 9 1981. I had started my search for you two years earlier at the age of 23. Id been told by my adoptive parents that you had died, but in my heart I never believed them. So I contacted the orphanage in 1979 and spoke to the very same Moral Welfare Officer, Mary McFadden, who had taken me from your arms all those years ago.

I never told you that Id tracked you down after all that searching and found, to my delight and terror, that you had lived less than nine miles from where I grew up, five miles from where I worked as a nurse. Neither did I tell you who I was because I feared I might lose you again, that seeing me and experiencing the guilt, shame and terrible sadness at our parting may have sent you fleeing. I just couldnt risk losing you again, so I didnt say a word. I dont know if that was the right thing to do, but it gave me a chance to get to know the real Bridget, not the Tipperary Mary character you had become in the pubs and streets of the city we shared.

When I discovered you were very much alive and living in Balsall Heath, my head spun with shock, not least by the news that at the time you were on probation for causing criminal damage! I knew I had to see you, though it took months before I came up with a plan. But my courage had temporarily deserted me. I decided that it was important to meet you from behind the safety of my district nurses uniform (though, of course, I wasnt officially your nurse). Id learnt enough about your fragile state of mind and health, to instinctively know that there was simply no other way. My uniform was the passport to you. It helped me to approach you and show you that, above all else, I was there to help.

Id been warned what to expect; the local drunk, the bag lady, Tipperary Mary with a bottle in her hand and a raised fist to the world, and at first you were wary of me, unable to trust a soul, arguing and fighting with a drink or three inside you. Over time, I came to understand so much more about your life, mum. While you never knew that the district nurse who came and tended you for nine years was, in fact, your long-lost daughter, Little Phyllis, as you called me.

While I put cream on your cuts and bruises (earned from nights fighting in dodgy pubs), gently combed your matted hair or helped you shower and dress, you talked to me, telling me of the horrors that lay in your past. These things were so hard for me to hear, yet I yearned for your history because it is mine, too. You told me snippets and anecdotes, sometimes laughing, sometimes swearing, your face twisted with painful recollection, and over time I pieced them all together. The fragments of your story became a living, breathing whole over that life-changing nine years, and through that I grew to know and love you, and I vowed to let the world know what it was that had driven you to the life you now led.

I still remember that day when I first met you. I couldnt stop staring. My eyes travelled the contours of your bruised and swollen face, the lines that showed me youd had a hard life, and I recall the thrill of noticing that we both had the same piercing blue eyes, the same pretty nose. I had never looked like anyone before, as any adopted child or orphan would understand.

But there was something else about your face that was familiar to me, more than just a family resemblance. I later realised with amazement that our paths had crossed very briefly years earlier, when I was working as a nurse in the A&E department of Dudley hospital and you had been brought in with a head injury after a drunken fight. I had no idea who you were at the time but I remember thinking then, that underneath all the bluster and shouting was a very vulnerable woman.

I listened to you for hours over the years when I cared for you. The only times it was impossible to be with you were when you were roaring drunk. On those days Id make my excuses and leave, your pale face appearing at the window as I went, as if to say come back. And so I always did. For years I had the privilege of looking after you, the mother Id never known, the daughter you thought youd lost.

In remembering our time together, I am still struck by your lack of bitterness, despite the chaos you were born into. You never complained. You shouted, you cried even, but you were never bitter, and I admired you for that. I saw clearly how you drank to numb your pain, and I have never blamed you for that either, nor for giving me up.

I have talked about my own life, growing up as an adopted child, and how I came to find you again, in my book Finding Tipperary Mary , but I felt it was now time to tell your life story, leading up to the day when our paths crossed again. While writing I have tried to give you the voice you never had as a child or as a vulnerable young woman. In reliving your life through your words, the stories you told me, and the research I have done here and in Ireland, I have come to understand you better. And the demons that drove you out of Ireland, from which you never seemed able to escape.