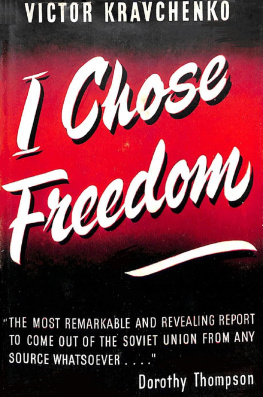

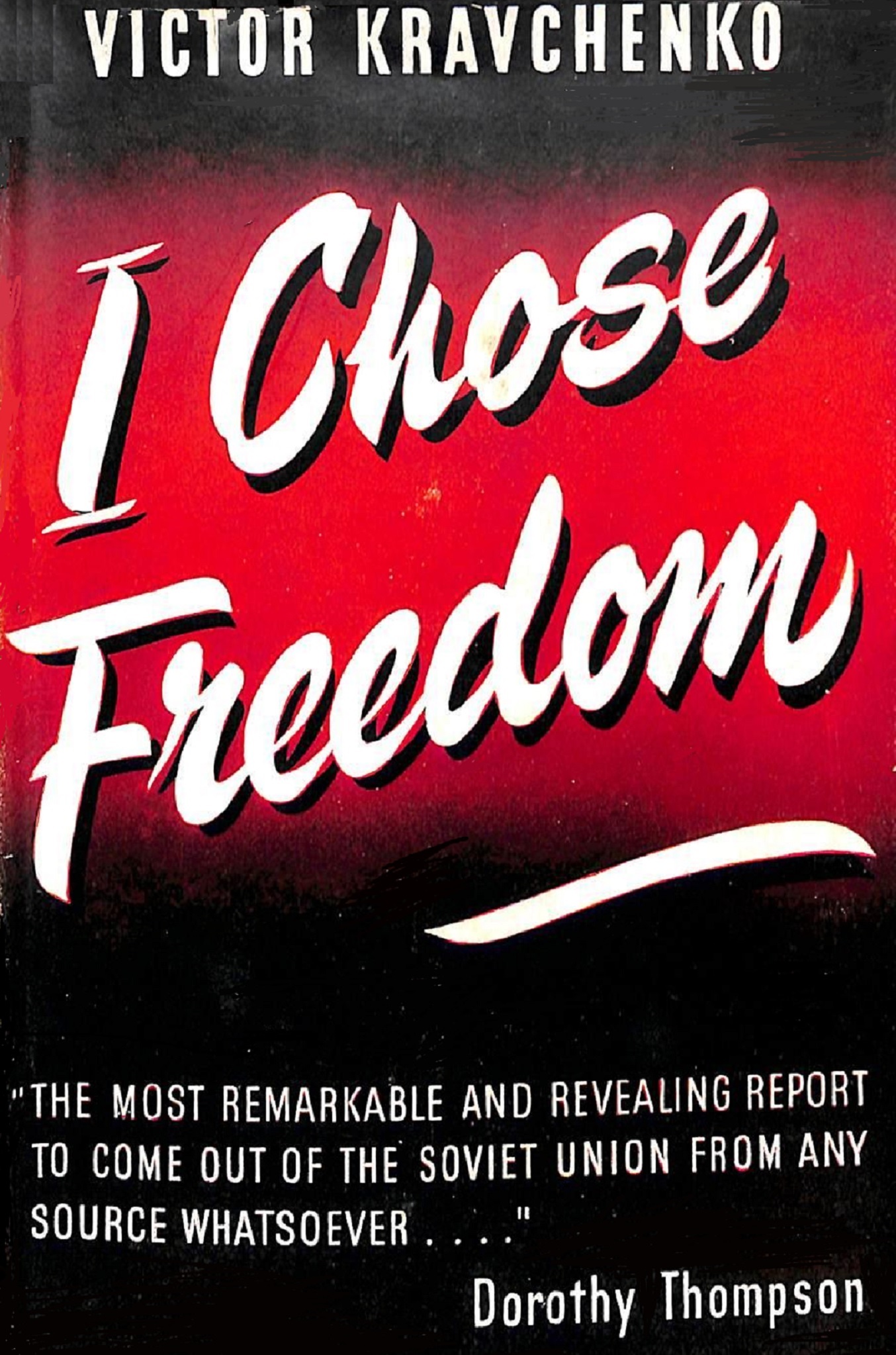

Kravchenko - I Chose Freedom

Here you can read online Kravchenko - I Chose Freedom full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: Hauraki Publishing, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:I Chose Freedom

- Author:

- Publisher:Hauraki Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

I Chose Freedom: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "I Chose Freedom" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

I Chose Freedom — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "I Chose Freedom" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our bookspicklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1946 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2016, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

I CHOSE FREEDOM:

The Personal and Political Life of a Soviet Official

BY

VICTOR KRAVCHENKO

Contents

EVERY MINUTE of the taxi ride between my rented room and Union Station that Saturday night seemed loaded with danger and with destiny. The very streets and darkened buildings seemed frowning and hostile. In my seven months in the capital I had traveled that route dozens of times, light-heartedly, scarcely noticing my surroundings. But this time everything was different this time I was running away.

The American family with whom I lived in Washington had been friendly and generous to the stranger under their roof. When I fell ill they had watched over me with an easy unaffected solicitude. What had begun as a mere financial arrangement had grown into a warm human relationship to which the barrier of language added a fillip of excitement. I sensed that in being kind to one homesick Russian these good Americans were expressing their gratitude to all Russiansto the brave allies who were then rolling back the tide of German conquest on a thousand-mile front. They gave me full personal credit for every Soviet victory.

My rent was paid for a week ahead. Yet I left the house that night without a word of final farewell. I merely said that if my trip should keep me out of town beyond Tuesday, they had my permission to let the room. I wanted my hosts to be honestly ignorant of my whereabouts and of my intention not to return, should there be any inquiries from the Soviet Purchasing Commission.

For several days, at the Commission offices, I had simulated headaches and general indisposition. Casually I had remarked that morning to a few colleagues that I had better remain home for a rest; that I might not come in on Monday. I was playing hard for an extra day of grace before my absence would be discovered.

After collecting my March salary I insisted on straightening out my expense vouchers for the last trip to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and the trip to Chicago before that. It appeared that about thirty dollars were still due to me. The idea was to erase the slightest excuse for any charges of financial irregularity to explain my flight. I also made sure that all my papers were in perfect order, so that others could take up the work where I had left off.

Later, when the news of my getaway was on the front pages of the Washington and New York papers, some of the men and women at the Commission must have recalled a peculiar warmth in my talks with them that Saturday, a special pressure in my handclasp when I said So long. They must have realized that I was bidding them a final and wordless farewell. Never again, not even here in free America, would any of them dare to meet me. In the months of working together some of these people had come close to me; without saying much we had understood one another. Had I been able to part with them openly, emotionally, Russianly, some of the weight that pressed on my spirits would assuredly have been lifted.

It was a chill, starless night. The railroad station seemed to swarm with threats. What if I ran into some colleague and he sounded the alarm? Certainly the two suitcases and the unauthorized journey would instantly arouse his suspicions. What if Comrade Serov or General Rudenko already had discovered my plans? As if in answer to these fears, I suddenly caught sight of a Red Army uniform. I went cold with dread. Pulling my hat lower over my eyes, drawing my head more deeply into the raised collar of my overcoat, I slunk along the wall, keeping my back turned to my countryman.

Because Soviet officials always travel in Pullman style, I took a seat in a plebeian coach. That reduced the risk of meeting anyone who knew me. In the dimmed-out, crowded, somnolent car I was alone with my thoughts.

For a long time I had known that this decisive hour was inevitable. For months I had planned the flight. I had looked forward to it as a release from the maze of hypocrisies, resentments and confusions of spirit in which I had wandered for so many years. It was to be my expiation for horrors about which, as a member of the ruling class in my country, I felt a sense of guilt.

But now that it was actually happening, there was in it no exhilaration, no lift of new freedom. There was a painful void in which fears and self-reproach echoed so loud that even the sleepy soldiers and sailors in the smoke-filled car must hear them.

I am cutting my life at its roots, I thought to myself. Irrevocably. Perhaps forever. This night I am turning myself into a man without country, without family, without friends. Never again shall I see the faces or press the hands or hear the voices of relatives and friends who are bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh. It is as if they were dead and therefore something precious within me is dead. Forever and ever there will be this emptiness in my life, this dreadful void and aching deadness.

So far as the land of my birth is concerned, I shall be an official outcast and pariah. Automatically the political regime into which I poured a lifetime of toil and faith will pronounce a sentence of death upon me. Always its secret agents will haunt my life. They will trace my steps and keep vigil under my windows and, if ordered by their masters, will strike me down. And these Americans among whom I hope to anchor my new lifehow can they ever understand what it means for a Russian Communist to break with the Soviet dictatorship? They are so blessedly innocent, these Americans.

In my home land, those who worked with me and befriended me, let alone those who loved me, will be forever tainted and suspect. To survive they will have to live down my memory. To save themselves, they must deny me and disown me, as in my time I pretended to deny and disown others who incurred the vengeance of the Soviet state.

Did I have a moral right to endanger these innocent hostages in Russia in order to indulge my own conscience and pay my own debt to truth as I saw it? That was the cruelest problem of all. What would my pious grandfather, Fyodor Panteleyevich, that upright servant of God and Tsar, have thought of my action if he were still alive? What will my father, that fanatical Russian revolutionist, say if he has survived two years under the brutal German occupation?

There was consolation, at least, in that train of thought. Grandfather never understood why his son Andrei, my father, opposed the Tsar and the tradition of the ages. But because Andrei believed deeply and was willing to go to prison for his strange new faith, grandfather always ended his reproofs with a blessing. As for my father, though he loved his wife and his children, he had not scrupled to expose us to hunger and tears to serve his cause. He would understand and approve; of that I had no doubt.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «I Chose Freedom»

Look at similar books to I Chose Freedom. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book I Chose Freedom and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.