James Holland

THE EASTERN FRONT 19411943

with illustrations by

Keith Burns

Contents

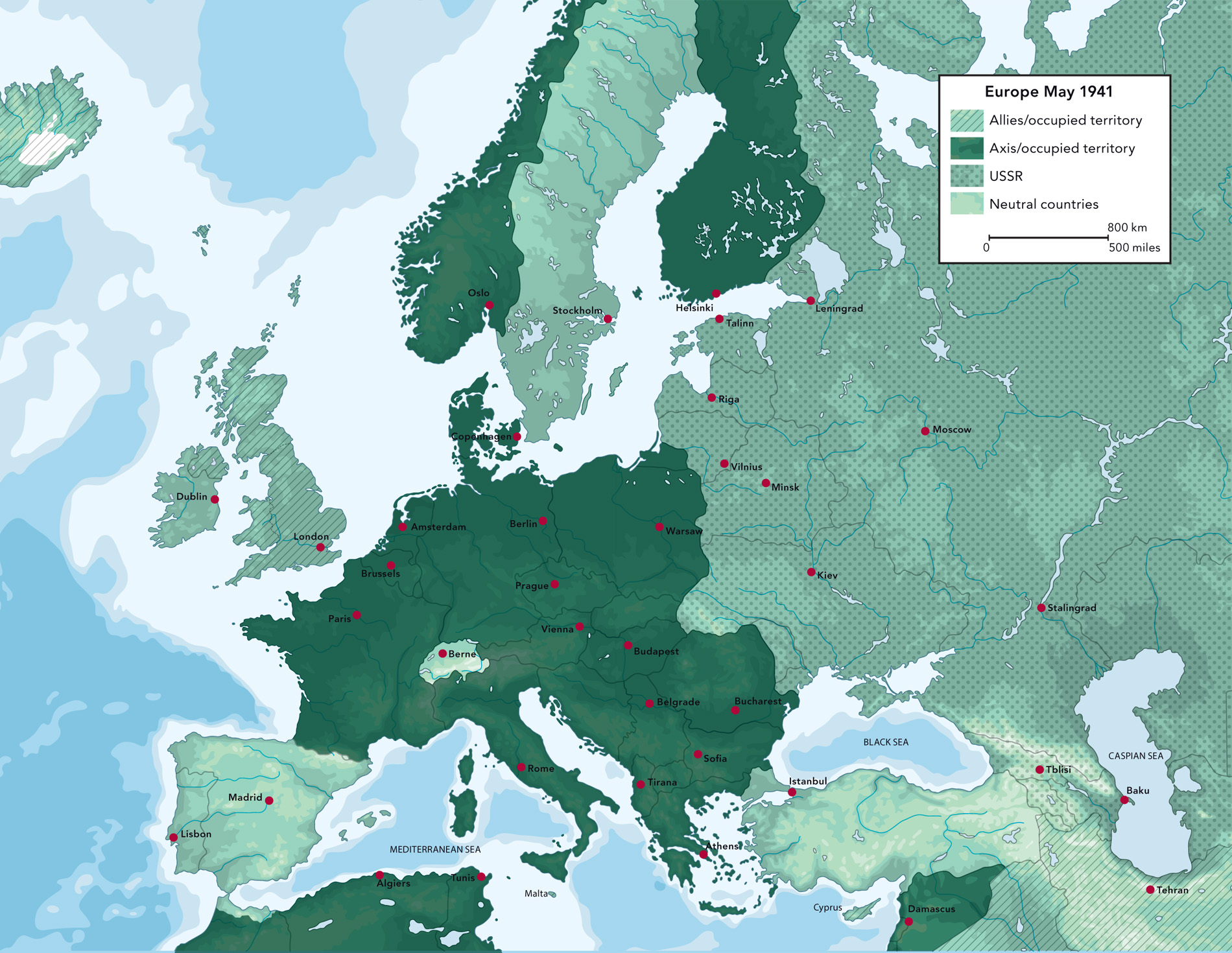

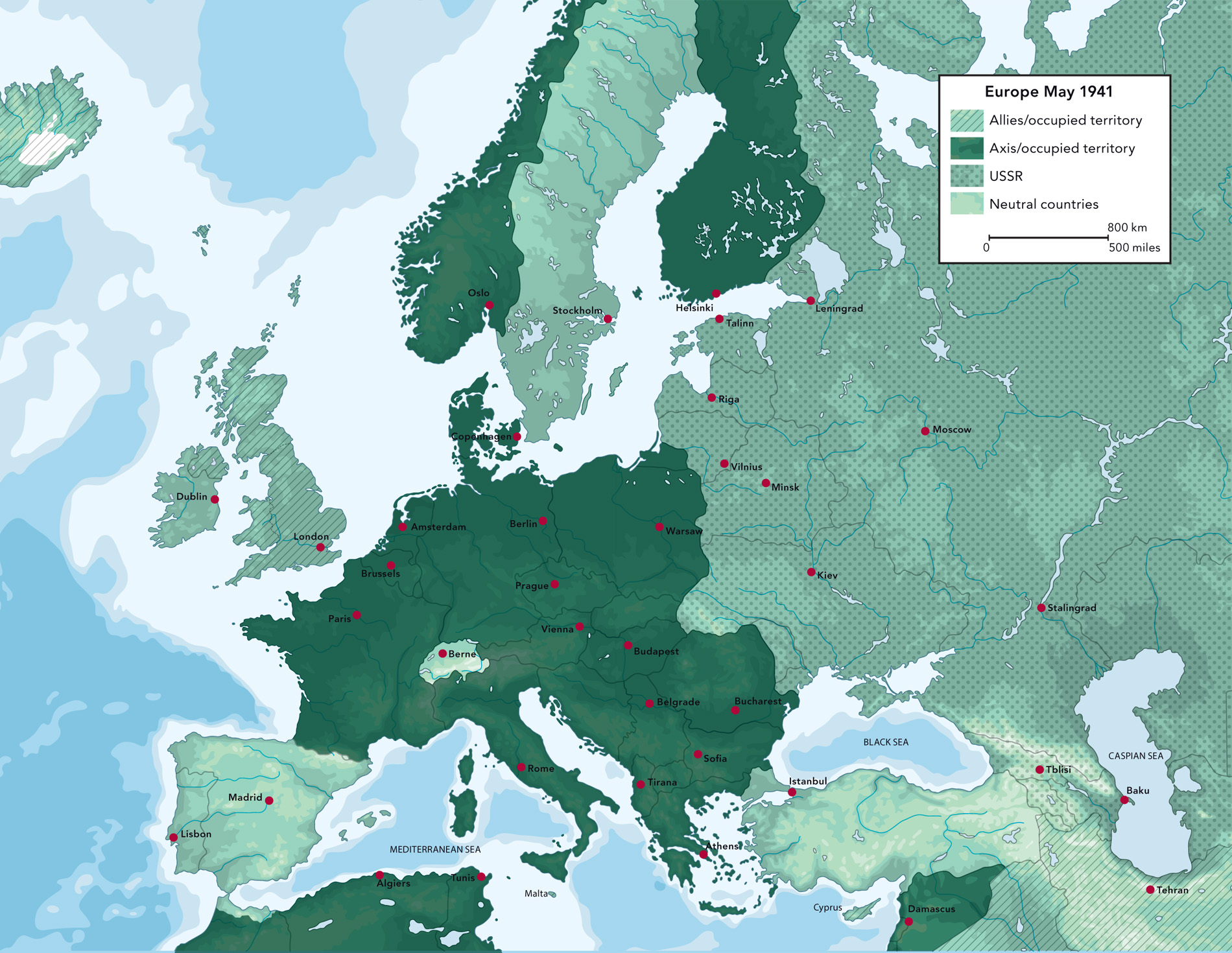

Operation BARBAROSSA was launched early on 22 June 1941, just a few weeks after the invasion of Crete, and was the largest clash of arms the world had ever seen. Germany had amassed more than 3 million men, a colossal number, yet in truth Adolf Hitlers forces were not really ready for a campaign on this scale. Hitler had originally intended to invade the Soviet Union once France and Britain had been defeated and Europe subjugated; as a veteran of the defeat of the First World War, he understood the danger of fighting on two fronts and overstretching Germanys meagre resources.

Yet Britain had not been defeated, and hovering in the background was the United States, with its huge economic potential and open hostility to Nazi Germany. Already Germany was running short of vital supplies, but especially food and oil, and plundering the Soviet Union now seemed the best chance of making up these shortfalls. Hitler was confident of success after all, Germany had recently defeated mighty France in six weeks, while the Red Army had been given a bloody nose by lowly Finland during what was known as the Winter War of 193940.

The trouble was, the Soviet Union was more than ten times the size of France and the Low Countries, and Germany had a force that was only slightly larger than that of the previous year when Hitler attacked in the west. Whats more, he had only 30 per cent more panzer forces, the German elite units that had been the spearhead of victory in France. As in France, most German troops were to advance into Russia on foot and by horse. The difference was that the attack front for BARBAROSSA was some 1,200 miles long.

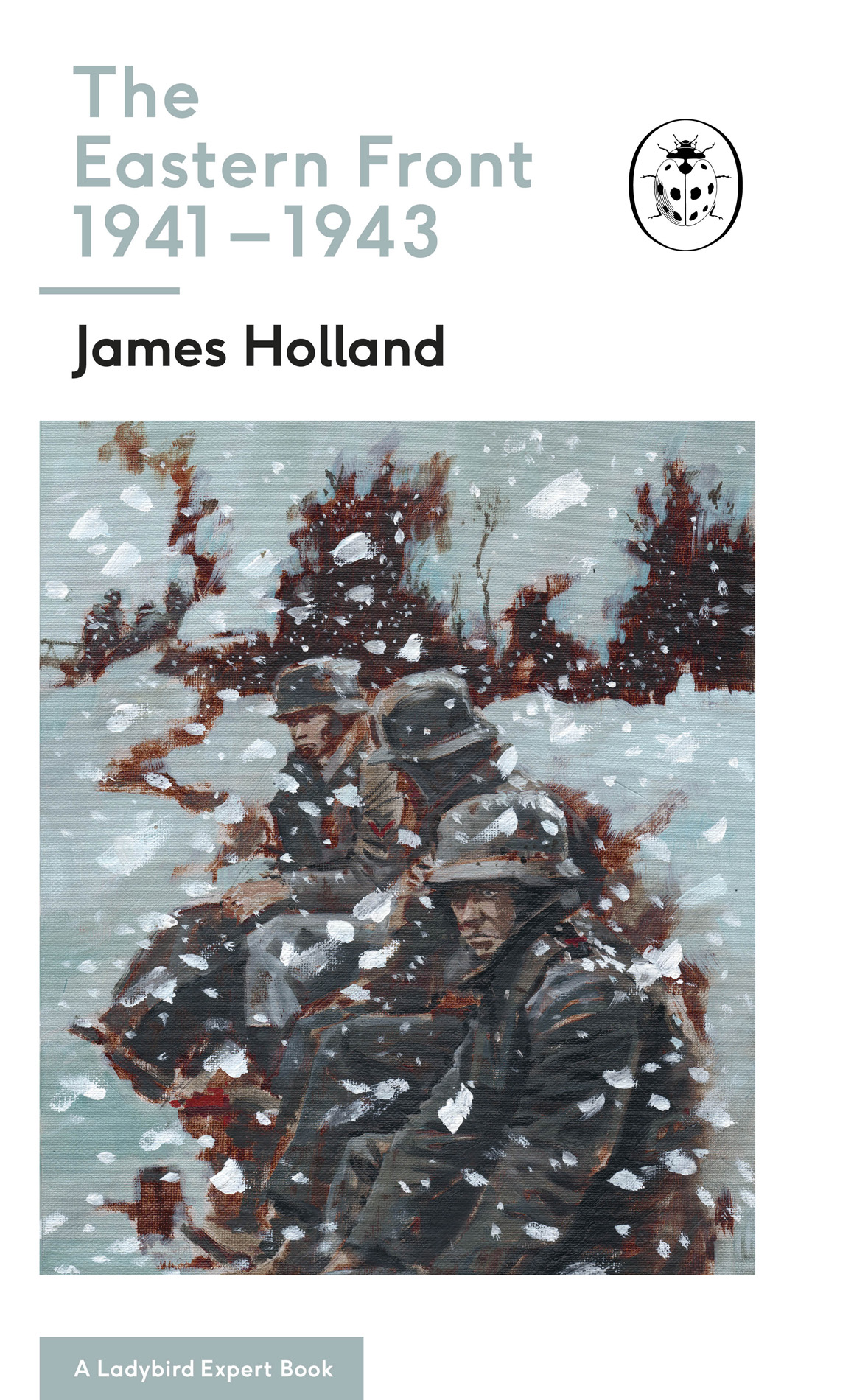

German troops advance into the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941.

Nothing less than complete annihilation of the Red Army would do, and really this had to be achieved within 500 miles the effective range within which the Germans could operate with the kind of speed and weight of force needed before their supply lines became over-extended and their advance ground to a halt. This was a tall order even for an army full of confidence and flushed with victory. The invasion was also to be conducted with brutal violence. The upcoming campaign, Hitler told his commanders, is more than a mere contest of arms. It will be a struggle between two world views.

The General Staff of the Wehrmacht the German armed services had already put together a plan to take the farmlands of the Ukraine. This would mean starving some 2030 million Soviet citizens, but Nazi Germany viewed it as a war of survival so this was considered regrettably acceptable. The Soviet leadership and intelligentsia were also to be exterminated. Hitler told his generals they had three months to win this victory, after which they would then turn back west and deal with Britain once and for all.

To begin with, all seemed to go spectacularly well, helped by the Soviet leader Joseph Stalins curious refusal to accept any warning sign of an imminent attack and despite massive German build-up along the border in former Poland. In fact, BARBAROSSA had been the worlds worst-kept secret.

Overwhelming force along what was initially a 500-mile front gouged out huge chunks of Soviet territory in the first fortnight of battle as the German armies swept forward, while above, the Luftwaffe hammered the Red Armys air forces. The Baltic States were swiftly overrun in the north, while in the centre much of former Poland was swept aside. Once again, the German armies seemed unstoppable.

Stalin appeared to have been briefly frozen with panic but quickly recovered. On 30 June he formed a war cabinet, the Peoples Commissariat of Defence (GKO), and the next day spoke to the people, appealing to their patriotism. At the same time, the security services were united under the Peoples Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) and ordered to clamp down even harder on defeatism and deserters, and to ensure there was no slackening of the struggle for survival.

Meanwhile, Hitler now began meddling in military matters despite having no qualifications for such high-level interference. On 19 July, he ordered that Leningrad in the north and the Ukraine in the south were the priorities and that his two precious panzer groups, currently pushing towards Moscow, should be sent to help with these drives once Smolensk, 360 miles south-west of the capital, had been crushed. The Soviet capital would be left to the Luftwaffe even though there were nothing like enough bombers to do the job.

Four days later, he changed his orders again, now demanding that the Luftwaffe support the southern drive and also the Finns, who were advancing against Leningrad in the north. He thought this would deter the British from intervening in the Arctic. At the time there was no possible way in which Britain could mount such an operation, something that was glaringly obvious to anyone with a basic knowledge of planning. Moscow was barely bombed at all.

Another directive was issued on 30 July and yet another on 12 August as Hitler obsessed over his flanks and the slowing up of their advance. By this time, the Red Army was starting to regain its balance, while the Germans were reaching the limits of their lines of supply.

German Heinkel 111 bombers attack Moscow.

Gnther Sack was a young anti-aircraft gunner attached to the German 9th Division in Army Group South in the Ukraine. In the second week of July his team suffered a puncture on their gun carriage, which held them up, then on 15 July their truck broke down with a seized engine. Then the trailer broke again, so that it wasnt until the end of July that they finally caught up with the rest of the division. His and his crews experience was a common one.

Meanwhile, a further 5 million men had been called up to the Red Army. The Soviets had been horrifically mauled in the opening stages of BARBAROSSA but they had not been completely defeated. Far from it. We very soon had to accustom ourselves, wrote Hans von Luck, an officer in the 7th Panzer Division, to her almost inexhaustible masses of land forces, tanks, and artillery.

The German advance was once again increasingly dependent on her railway network, but the Soviet Union operated on a different gauge. This meant changing the tracks as they moved east, because Stalin had also ordered a scorched earth policy as the Red Army fell back. All factories, bridges, farmland and infrastructure were to be destroyed so the Germans could not use it. On 24 June, Stalin had also ordered the establishment of a Soviet or council for Evacuation. The vast bulk of the USSRs industry was to be moved lock, stock and barrel to the Urals, some 600 miles east of Moscow. By the beginning of August this was already well under way.

Next page

German troops advance into the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941.

German troops advance into the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941.

German Heinkel 111 bombers attack Moscow.

German Heinkel 111 bombers attack Moscow.