Series 117

This is a Ladybird Expert book, one of a series of titles for an adult readership. Written by some of the leading lights and outstanding communicators in their fields and published by one of the most trusted and well-loved names in books, the Ladybird Expert series provides clear, accessible and authoritative introductions, informed by expert opinion, to key subjects drawn from science, history and culture.

Every effort has been made to ensure images are correctly attributed, however if any omission or error has been made please notify the Publisher for correction in future editions.

MICHAEL JOSEPH

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Michael Joseph is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2018

Text copyright Suzannah Lipscomb, 2018

All images copyright Ladybird Books Ltd, 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover illustration by Martyn Pick

ISBN: 978-1-405-93355-1

Suzannah Lipscomb

WITCHCRAFT

with illustrations by

Martyn Pick

Witches are everywhere

The witch who haunted my youth was Roald Dahls Grand High Witch. She had square-ended feet without toes, a head as bald as a boiled egg, and thought children smelt of dogs droppings. I found her genuinely terrifying.

Beyond childrens stories, the witch remains culturally versatile. In horror films, TV shows (think Melisandre in Game of Thrones) and misogynistic depictions of politicians (neither Hillary Clinton nor Theresa May has escaped the charge), the figure of the witch retains her potency to attract and repel. She is a synonym for evil, inversion and desire, and has always been so.

Witchcraft beliefs have been around for thousands of years. In ancient Greece, around 330 BC , alleged witch Theoris of Lemnos was prosecuted for casting incantations and using harmful drugs. Roman poet Tibullus promised his mistress in c. 30 BC that he had found a truthful witch to perform magic rites and spells so that her husband would not know she was having an affair. The Chronicle of AD 354 records the execution in the reign of Tiberius of forty-five sorcerers and eighty-five sorceresses, probably in AD 16/17. In AD 371, Emperor Valentinian forbade haruspicy (divination using the entrails of animals) for harmful ends. Under the French king Clovis, in the early sixth century, those who practised magic were to be fined; Charlemagne ordained in 789 that night-witches should be executed, and Athelstan, King of the Anglo-Saxons (92439), ordered punishment for anyone casting a spell that led to death.

Witch myths

Witches have always been with us, but there was a moment in history when they were perceived to be especially dangerous. In Europe between 1450 and 1750 large numbers of people were persecuted, prosecuted and executed for being witches. It hadnt happened before, and it hasnt happened since. Why did it happen then?

To answer this, first we need to slay some myths

Myth No. 1: Witches were ducked on stools.

No, that was the punishment for scolds. Witches were swum.

Myth No. 2: All witches were burnt alive.

In England and New England, witches were hanged not burnt; elsewhere, witches were strangled before burning.

Myth No. 3: The medieval Catholic Church was responsible.

No. The vast majority of trials took place in ordinary secular courts. The churchs only role was to link popular beliefs to a new idea of a conspiracy of witches headed by the Devil.

Myth No. 4: The Church burned at the stake an astounding five million women (Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code).

It would be astounding if true. In fact, about 90,000 people were prosecuted for witchcraft, and about half of them were executed.

Myth No. 5: The witch-hunt was an attempt to eradicate folk paganism.

There is no credible evidence that convicted witches were pagans or surviving adherents of an old, folk fertility cult.

Magic and the supernatural

In 1500, just about everyone believed in the utter reality and potent power of the supernatural.

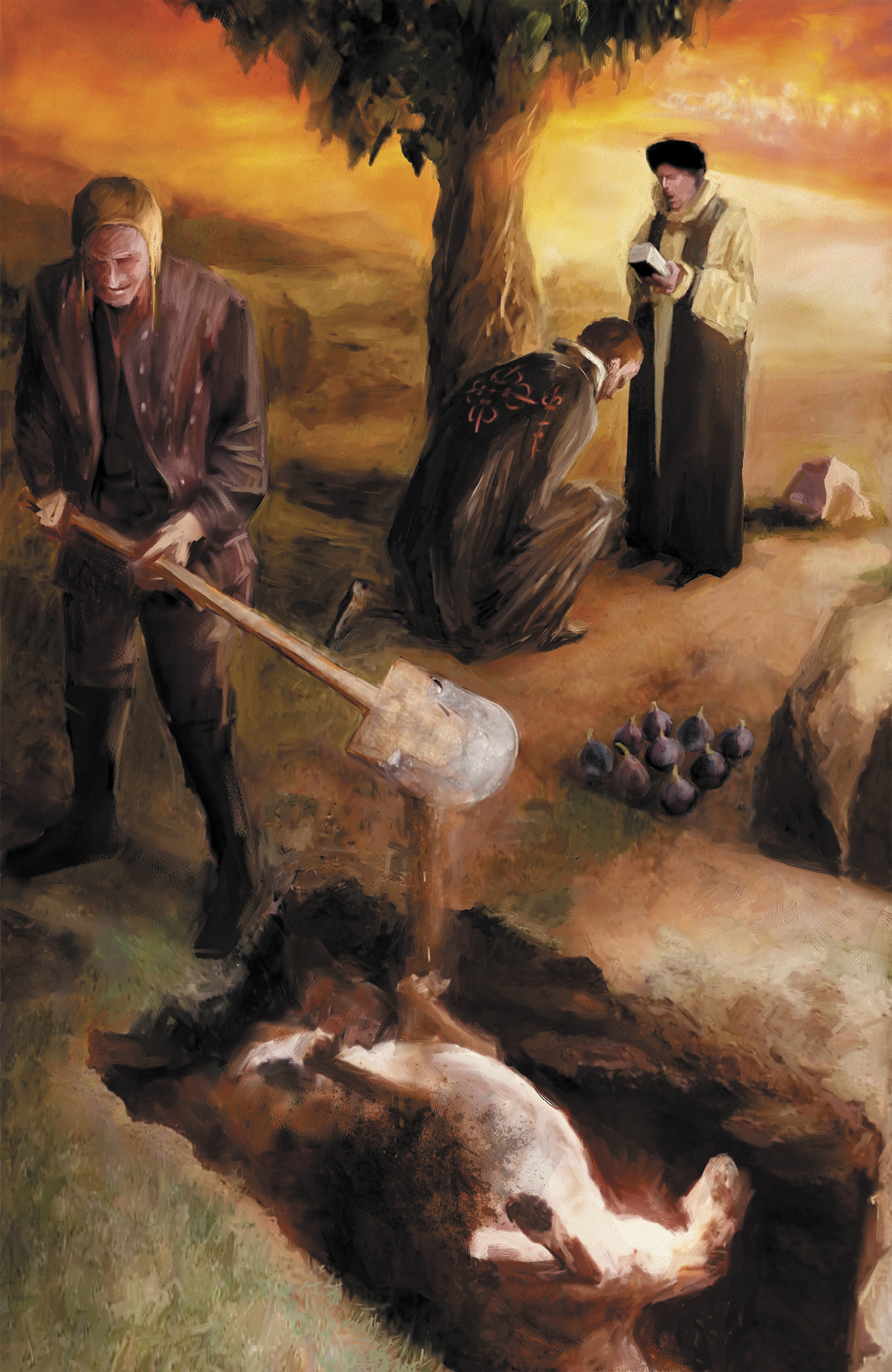

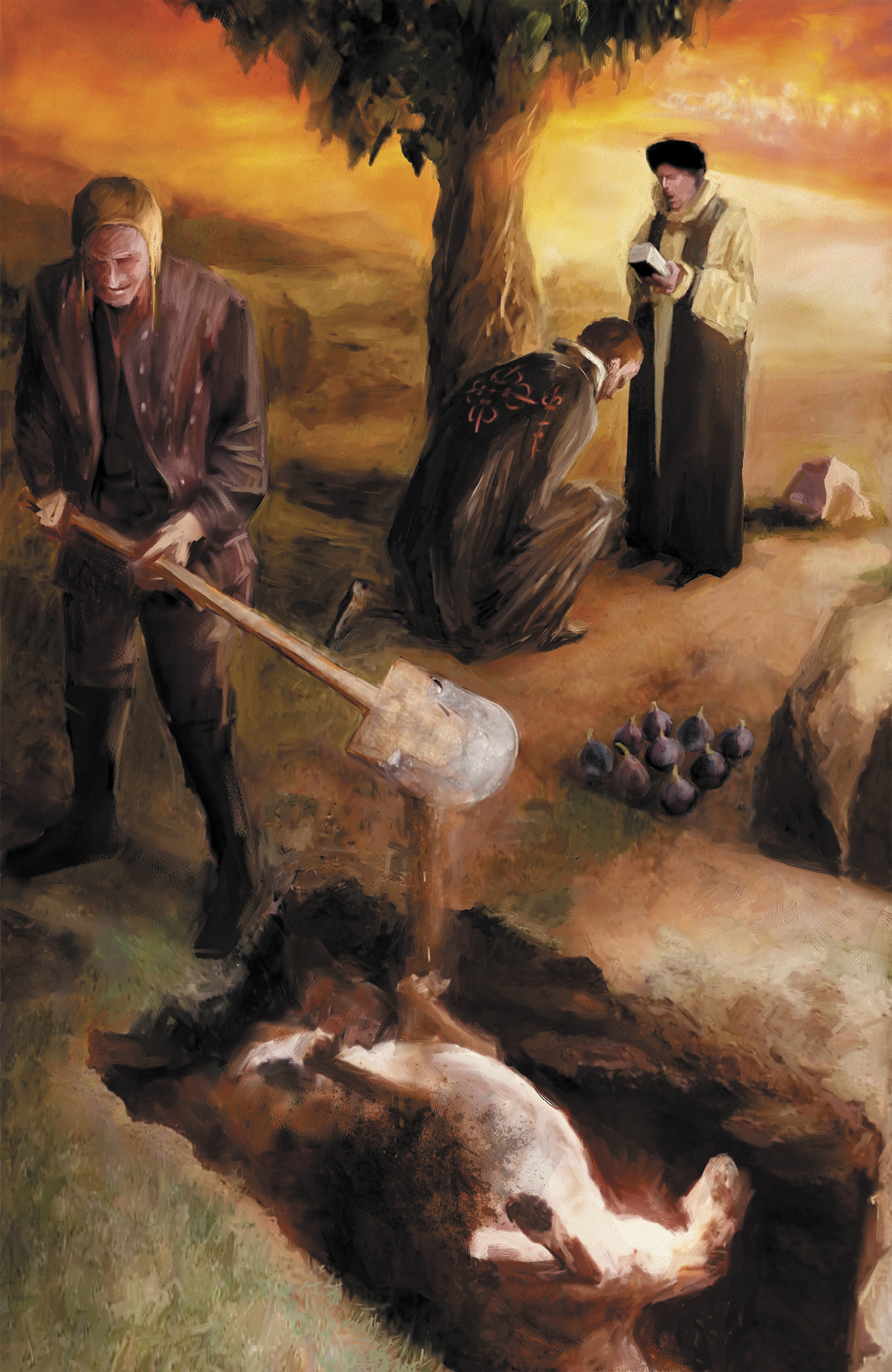

Magical practices and superstitions easily mingled with orthodox Christian belief. In 1517, Alonso Gonzlez de la Pintada described his cure for haemorrhoids: take the sick person to a fig tree, have him kneel facing east with his hat off, bless him, recite a Paternoster and an Ave Maria, then cut down nine figs and take them to a place where neither sun nor smoke can get at them. When the figs have dried out, the piles will be cured.

Magic could be benign. It could also bring good luck through amulets, carrying herbs or putting shoes in chimneys. It was usual to turn to a local practitioner of beneficent magic (known in England as a cunning man or woman) to seek assistance when things were uncertain or inexplicable.

Cunning folk offered cures for infertility or love potions. They claimed the ability to divine the location of stolen goods and the identity of thieves. A common method was to hang a sieve by shears and nominate the suspects: the sieve would rotate by magic! when the guilty party was named.

Magical practitioners believed they could heal sickness by burying an animal alive, boiling eggs in urine or tying salt and herbs into cows tails. They also frequently identified sickness as witchcraft, helped the afflicted to name the person responsible and forced the witch to heal their victim (these moments of reconciliation acted as therapy, creating a placebo effect).

Witches, the Devil and the Reformation

But the supernatural could also be malevolent. Witches were said to use magical powers to carry out maleficium (harmful magic), causing damage to property and injury or even death to people and animals. To do this, they drew on mysterious, supernatural power, which many believed the witch acquired through a pact with the Devil.

Belief in witches was orthodox doctrine. It was even in the Bible. Exodus 22:18 Thou shall not suffer a witch to live offered the ultimate justification for executing witches (although critics questioned the accuracy of the translation).

But the existence of belief in magic and witches is very different from the legal prosecution of witchcraft. So why were witches persecuted?

One possible explanation is that the witch-hunts happened in the aftermath of the Reformation, when there was a crackdown on all forms of superstition. Yet witch-trials happened in both Protestant and Catholic areas, and they werent directed by one set of believers against the other.

Next page