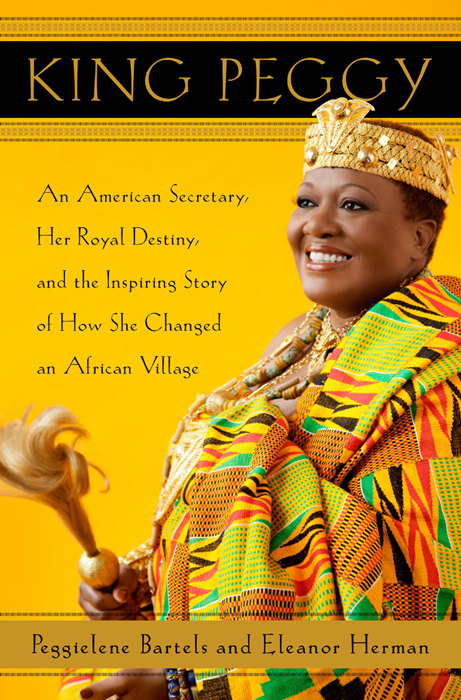

Copyright 2012 by Peggielene Bartels and Eleanor Herman

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.doubleday.com

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Insert photographs copyright 2012 by Sarah Preston

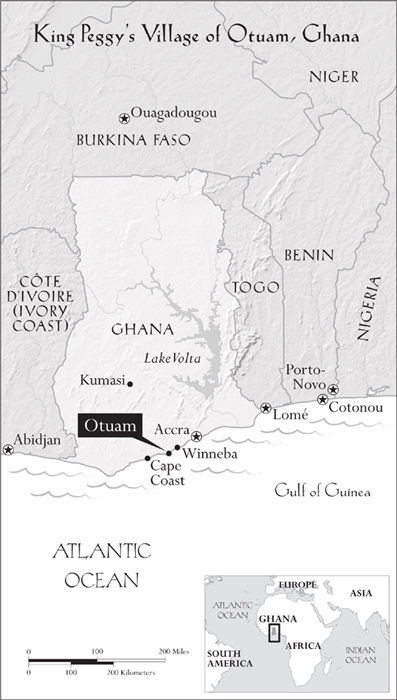

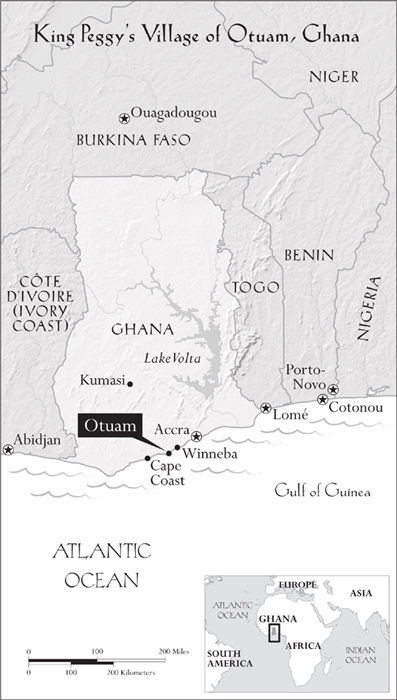

Cartography by Mapping Specialists

Cover design by John Fontana

Cover photograph Deborah Feingold

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bartels, Peggielene

King Peggy : An American secretary, her royal destiny, and the inspiring story of how she changed an African village / Peggielene Bartels and Eleanor Herman. 1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Bartels, Peggielene, 1953TravelGhanaOtuam. 2. GhanaKings and rulersBiography. 3. AmericansGhanaBiography. 4. GhanaSocial life and customs21st century. 5. Secretaries Washington (D.C.)Biography. I. Herman, Eleanor, 1960 II. Title.

DT512.44.B36A3 2011

966.7dc23

[B]

2011019544

eISBN: 978-0-385-53433-8

v3.1

To my mother, Madam Mary E. Vormoah, who was my best friend and made me the woman I am today.

PB

To the people of Otuam, and all the Otuams around the world, for their hope and joy in the face of poverty.

EH

Contents

Prologue

In the dream Peggy was back in Kumasi, a child again, walking home from school in her sky blue uniform with the round white collar. Usually the path was dusty in the dry season, pocked with puddles in the rainy season, but now it was smooth as marble; her black sandals glided over it and her feet remained clean.

The sky was a bright turquoise vault above her head, so beautiful it broke the heart, and the warm golden sun on her shoulders felt like a loving embrace. Just as she had every school day when she lived in Kumasi, in the dream she walked behind the kings palace, a rambling brick structure painted blue and white and built around a large courtyard where royal festivities were held. The Ashanti king of Kumasi, known as the Asantehene, was a very important leader with millions of subjects, and he was rich beyond measure because he owned some of the biggest gold mines in the world. All day at his palace, important visitors were coming and goingtribal priests, elders, government ministers, ambassadors, chairmen of important companies, and humble people asking him for justice.

She stood outside the rear of the palace and looked at it, wondering what was going on in there. But there was nothing for her, a skinny little girl, in a kings palace. And so she glided down the marble path to her home.

Because Peggy had the dream so many times she knew it must be a message from the spirit world. Like many Africans, Peggy understood that dreams meant something. They were not just random thoughts, fears, or hopes, or something from dinner irritating your intestines. Sometimes a dream was a message from God or Jesus, or from your ancestors, or even from the better part of yourself talking to the stupid part of yourself. Dreams were like encoded letters from the spirit world that must be carefully decoded and interpreted. They guided you in your choices, warned you of deception and accidents, or showed you the future.

What does the dream mean, Mother? Peggy asked when she called her mother in Ghana.

Mother thought about it a long while. Its been thirty years since you walked behind that palace to go to school in Kumasi, Mother said. Perhaps its just a memory.

But why would I have it so often, thirty years later? Peggy insisted. Here I am living in the United States all this time; theres nothing to remind me of the kings palace in Kumasi. The dream has to mean something.

A moment of silence dangled in the transatlantic air. Peggy could picture Mothers long smooth face and shining dark eyes as she considered the question. Finally, she said, Pray for God and the ancestors to show you what the dream means, Peggy. Perhaps, in time, they will.

Mother was right. God and the ancestors would show Peggy the meaning of the dream in their own time, but it would be long after Mother had joined them.

Part I

WASHINGTON, D.C.

AugustSeptember 2008

1

Is the king dead? Peggielene Bartels wondered as she stood in the small mail room off the lobby, rubbing her thumbs across the front of the envelope, the ugly red stamp UNDELIVERABLE splayed across the blue ink of the address carefully penned in her own hand. For the third time a letter to her uncle Joseph had boomeranged back from Ghana. Another resident jostled her apologetically as he took out his little silver key and opened his mailbox, but Peggy just kept staring at the letter.

Uncle Joseph was her mothers brother, and for twenty-five years he had been king of Otuam, a community of seven thousand souls where Peggys family had originated hundreds of years earlier. Periodically, when she had returned to Ghana to visit her mother, the two of them would drive to Otuam to see Uncle Joseph, known there by his royal title Nana Amuah Afenyi V.

The king of Otuam was a tall man with heavy-lidded eyes, the lower lids revealing a great deal of white below the iris. He had been director of all the prisons in Accra, Ghanas capital. In 1983 at the age of sixty-seven, he had retired and, upon the unexpected death of his sixty-three-year-old cousin, Nana Amuah Afenyi IV, was chosen the new king.

Peggy remembered Uncle Joseph as a gentle, smiling man who never raised his voice. A man always ready to forgive. A man everybody liked. Sometimes Peggy wondered how such a man could be a king when kings were supposed to be tough and strong. If she had been in his position, she wasnt sure she would have been so kind. She wouldnt have cared if some people disliked her as long as she was a good king, punishing evildoers who took advantage of the weak.

The last time she had seen Uncle Joseph was at her mothers funeral in 1997. He had arrived at her mothers home in Takoradi with a group of his elders, a kindness that even in her overwhelming grief Peggy had appreciated. For years she had regularly sent her mother money, and once her mother was in a better place where no money was needed, Peggy decided to send the money to her uncle out of respect. It was only one hundred dollars a month, but it went a long way in a Ghanaian town where many people lived on a dollar a day. And Peggy knew that even though Uncle Joseph was a king, he was not rich. His palace was falling down around his head, with a leaking roof and mildewed walls begging for spackling and fresh paint. And she worried that he might need medicine.

He had been grateful for the money, and the two had kept in touch in the eleven years since her mothers passing. Earlier that yearhad it been January?he had had a stroke and been hospitalized, but he had seemed to be recuperating. She had spoken to him on his cell phone now and then during his months-long stay in the hospital in Accra, and someone had picked up his mail for him at his post office box in Winneba, the city nearest to Otuam with mail service.